I was looking forward to using triangulation, a technique which was often discussed in the email lists.

My understanding is that if you have a confirmed match, and you have another match at the same segment, you can hopefully deduce the MRCA of all three of you. This, I believe, works as follows:

Suppose I have three matches – Match A, Match B and Match C. They are showing up in FtDNA or in Gedmatch or some such site. I have probably found them by using the ‘In Common With’ tool and discovered that these matches match each other as well as myself.

Suppose then, that I view them all in a chromosome browser and find that they all match on the same chromosome and basically on the same segment. Maybe one runs eg 5 to 13, one runs 7 to 10 and the other from 4 to 11. We have a segment from 7 to 10 which is matched on all three, same chromosome. This is what you need to start with.

If I have a segment 5 to 10, and another one 10 to 20, those segments did not necessarily come from the same ancestor. They are not relevant. The relevant portion is the exact same bit on each. However, in my segments above the longest – 5 to 13 – might be closer to me than the smaller ones.

I have many sections like this, and I have kept a note of them. However, I need more than this for it to be useful.

If I have identified my match with one of them, I have a good starting point. Suppose I have identified that Match A is a second cousin on the maternal side. Our common ancestor is one of my maternal great grandparents and I will be able to find them fairly easily. This gives me my first triangle – my own segment, my second cousin’s segment, and our common ancestor’s segment.

I have two other matches with that same chromosome, same segment. It’s time to look at their ancestors. Do they have our great grandparents in their tree? If so, it is easy. The triangle is much the same. If not, do they have an ancestor who lived in the same location as our great grandparents? If so, we need to build our tree and theirs at that point to find a connection.

If I find it, I have the MRCA and our match. If not, the next best thing is to take the other two matches – the ones who match each other and yourself on exactly the same segment, and see if I can find their common ancestor. If I figure out that both of them descend from John Appleyard of Onevillage in Sussex in 1830, then I can look through my own tree for an ancestor who lived in Onevillage at the same time. Failing that, an ancestor who lived nearby, an ancestor with a travelling job who went through that village, a runaway son or daughter who was located near that village … that type of thing. It is necessary to truly understand my ancestor’s lives to do this. It takes time, effort and concentration. Luckily it is enormous fun, but sometimes relies on access to the right resources.

This sounds so simple! Like everything else to do with DNA, I haven’t found it so. If a common ancestor or common location cannot be found, you can’t go any further. I have a confirmed maternal match for my example segment (the first pink segment) so the second match either matches the same ancestor on the maternal side, or it matches an unidentified ancestor on the paternal side. So the next thing to do, if we can’t find a link on the maternal side, is to look in the paternal tree for clues.

One thing that throws people out is when this match – as in my example – was an ‘In Common With’ match. This makes it seem likely that the match should be on the same side, but this really cannot be assumed. Communities used to be more isolated and people married the people they met. If all they met were the local families, you end up with a whole lot of interconnections.

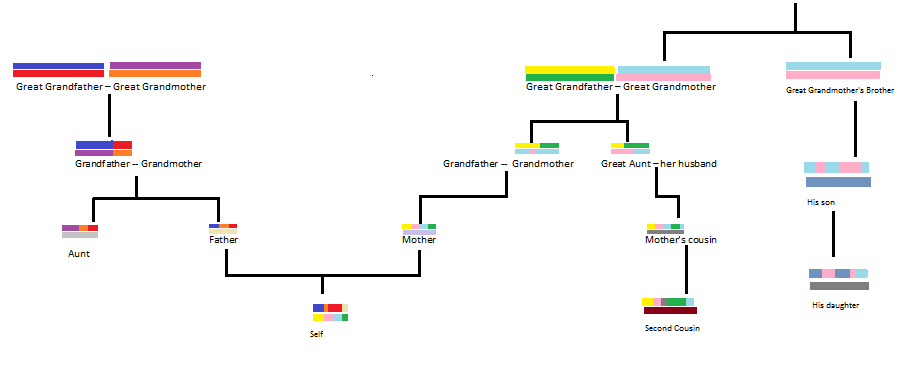

Here is my diagram showing how I think it works. I believe this diagram will enlarge if clicked.

In my diagram, each colour represents the sequence of DNA from that ancestor. We each get two copies of each chromosome, one from the mother and one from the father. This is greatly simplified because I am interested in how DNA from one or two specific ancestors has carried down. In this case, the two sets of great grandparents in this picture.

Thinking of my earlier example, I have myself, I have Match A (the second cousin), Match B (the more distant maternal relative) and Match C (the aunt on the paternal side). My matching segment is the orange block for the aunt, and the first pink block for the maternal matches. Notice that this block is in the same position and will show as the same segment numbers (roughly) for each match. But I can’t tell in my match list that Match A and B are pink and Match C is orange. Having that detail would make it all straightforward. The only thing I haven’t added into this diagram is another connection between the two sides. Just imagine that the paternal grandmother is the sister of the lady who marries the maternal great grandmother’s brother’s son. Then Match C will show as a close match to Match B through a different common ancestor. This is why ‘In Common With’ can be a guide to which matches to gather into the investigation in the first place, but doesn’t really tell you anything more.

This makes sense when you see the whole diagram, but try covering the top half with a piece of cardboard and just looking at the bottom samples. It is very hard to see how they might connect.

The important point being that I need every element I can find in making this connection. I need DNA matches on each side, I need as solid a paper trail as I can get, and I need a cautious and inclusive methodology. However, once I have made the identification, this is very useful in identifying further matches on the same segments, so it is well worth making the effort.

Clear as mud? Usually. I’ve come to the conclusion that mud is nothing to DNA.

Leave a Reply