In my family, irreplaceable family objects are still being lost with each year that passes, though the rate has slowed I hope. My recent road trip showed me how much has vanished in the last fifteen years. This is very much on my mind and after talking to neighbours I have realised it’s an all too common story.

I have also discovered that I am solely responsible for the survival of a few objects. This is encouraging and has given me a strategy for saving more. The trick is for each object to have its own story.

Ten years ago I became a member of a historical society which ran a museum. The museum underwent a process of accreditation while I was there and I learned a huge amount from it.

It was a challenging process for some of our members who had done things the same way for several decades, and couldn’t believe their way was less than ideal. It was challenging simply to relinquish control and allow the self-important Sydney upstarts to lay down the rules. Little country towns are like this.

The accreditation ran through every fascinating aspect of museum life, but the one which is of use here is the part about deciding which exhibits to keep and display. A lot of the process also applies to family heirlooms.

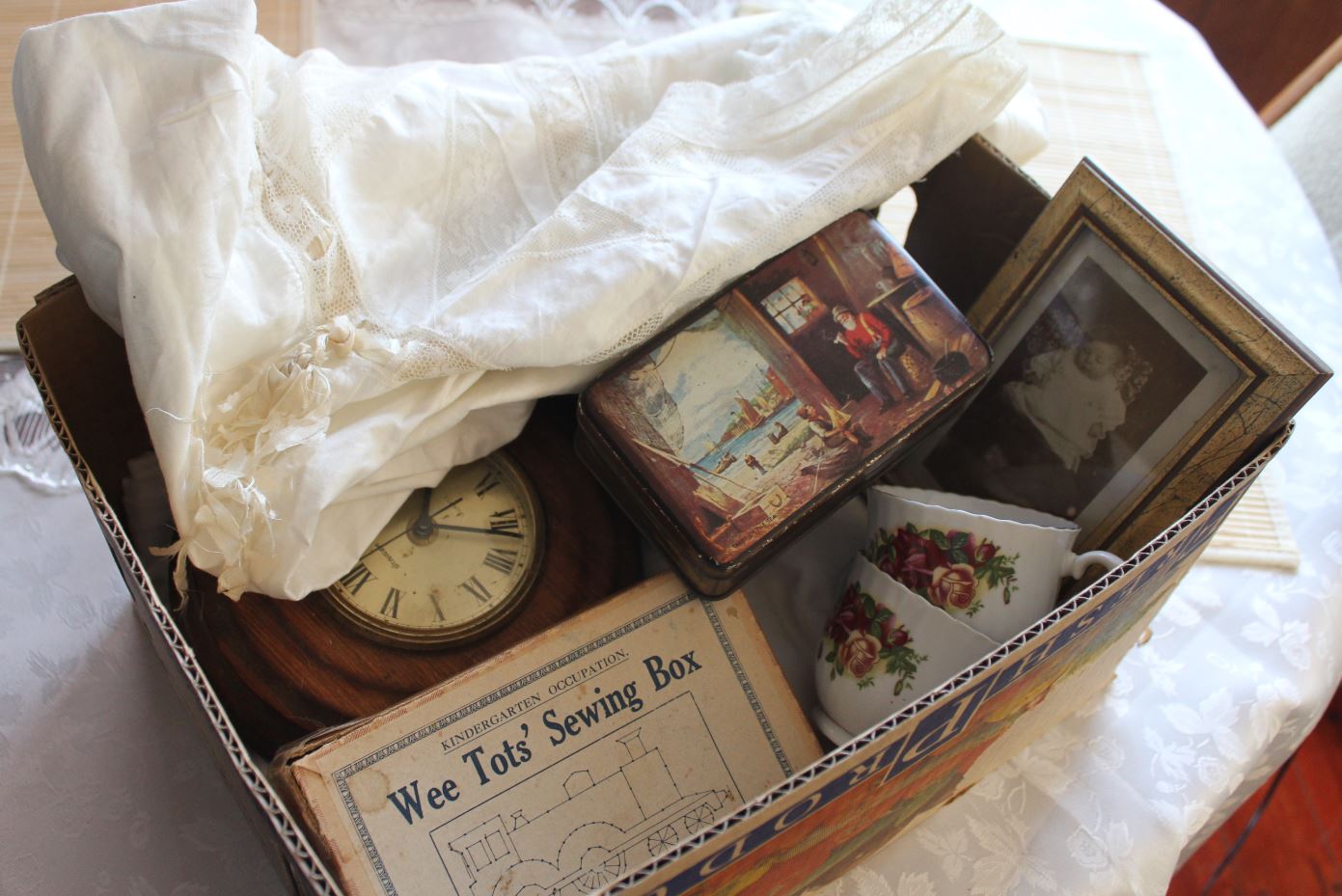

Small town museums are popular repositories for unwanted household items. Not so much in the last twenty years as antiques have become more valuable, but it still happens. Someone downsizes and into the local museum they go with their carton of things – teapots, picture frames, old irons, butter trays, perhaps a brown newspaper or two from the 1950s, a small collection of books. “They belonged to my father.” They’ll say. “He’s passed away now, and we don’t need them, but he was the first schoolteacher at the new school, you know, and it would be a shame to send them to the tip.”

A museum is a building of finite size. If it takes every single item at face value, there’ll soon be no room to move. The museum staff need a uniform method to pick the items of use to them from the items which are not of use. Otherwise, at some point there’ll be a fire, or an infestation of silverfish, or just a mammoth cleanout by new management, and everything will be lost.

Our homes are equally finite. Too much stuff and one day someone will send it all to the tip. They won’t see a collection of interesting objects. They’ll see wall to wall writhing dirty rubbish. I have never managed this viewpoint myself, but I’ve become aware that at least half my family do, and will act swiftly and irrevocably.

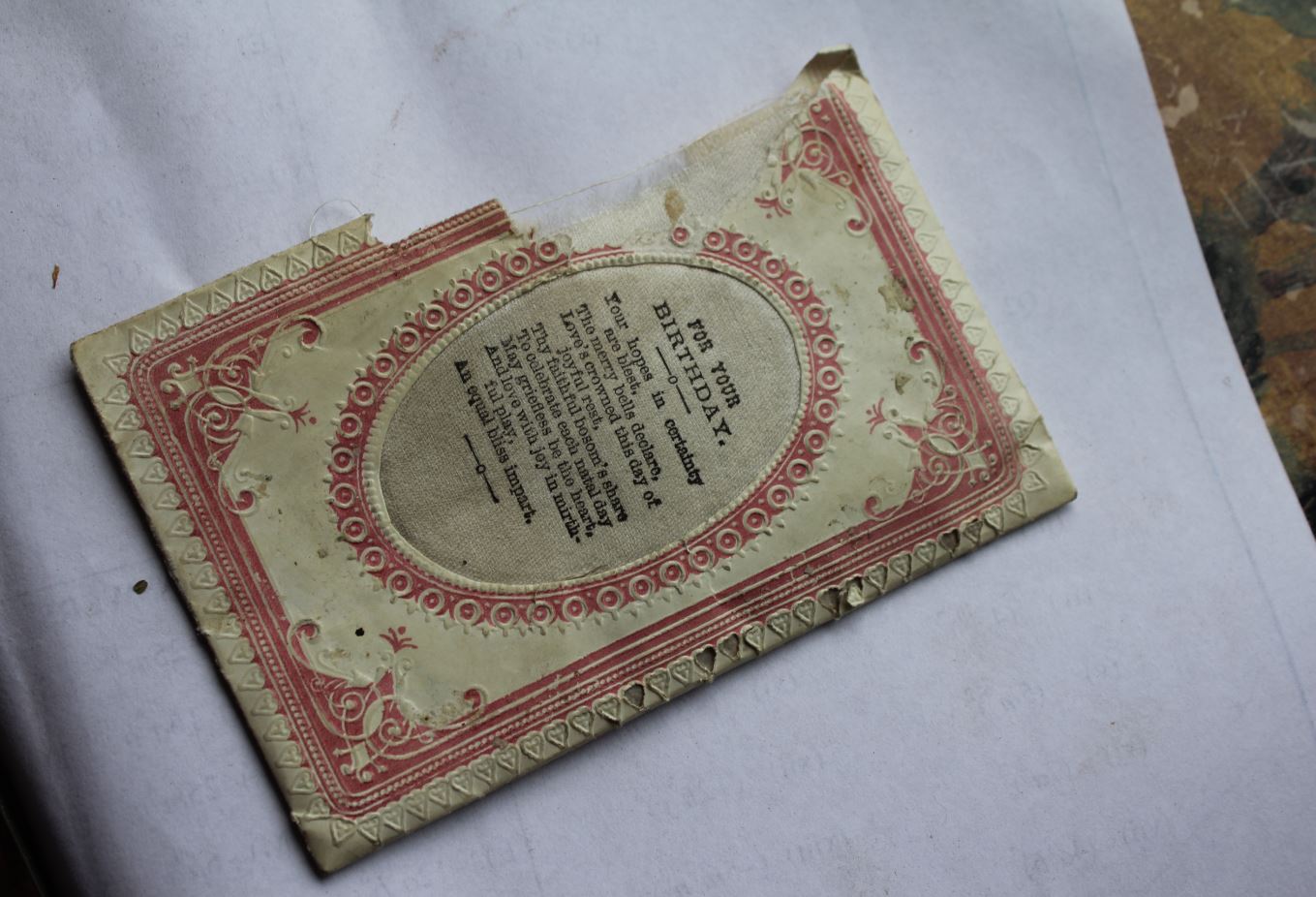

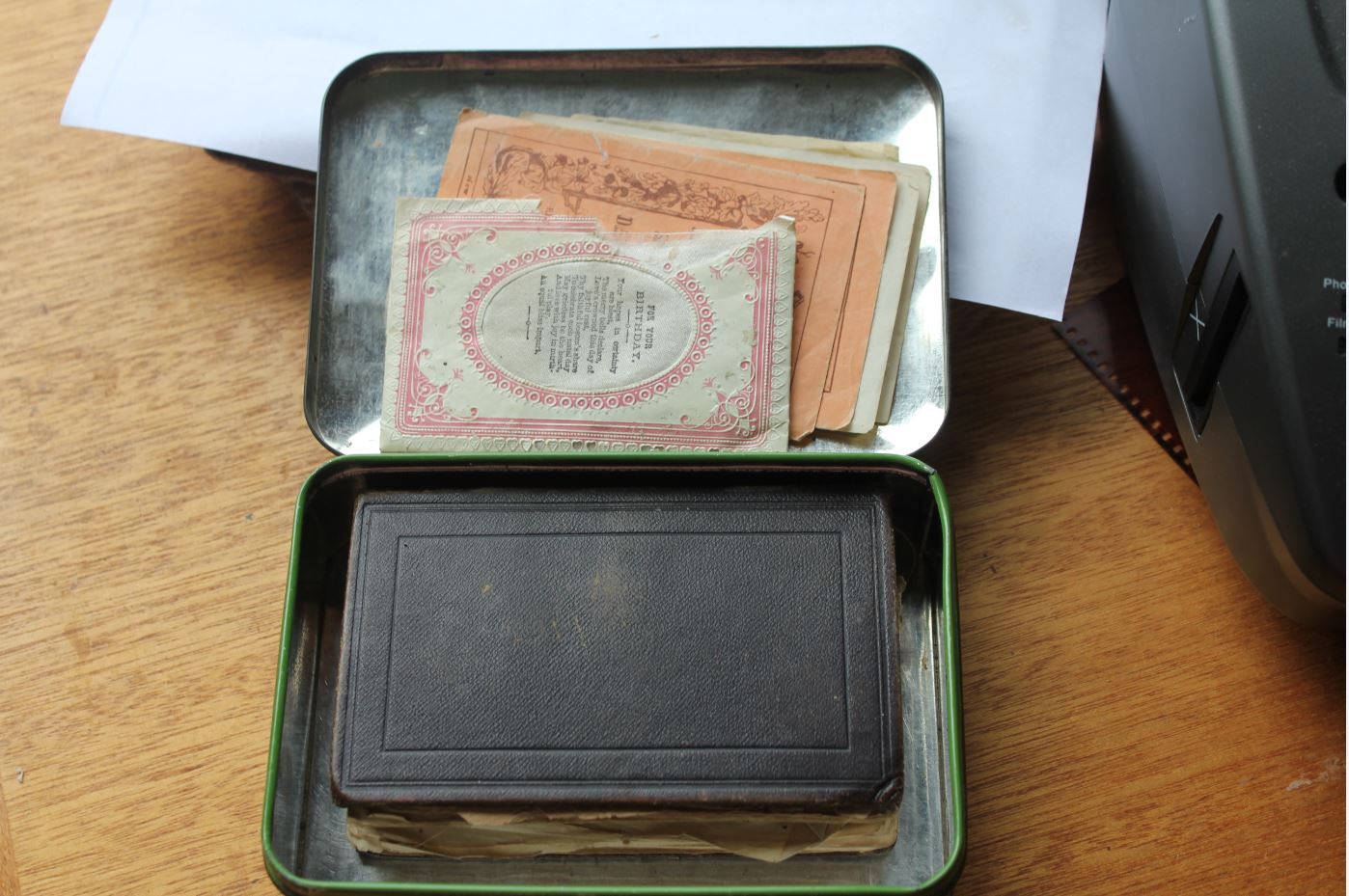

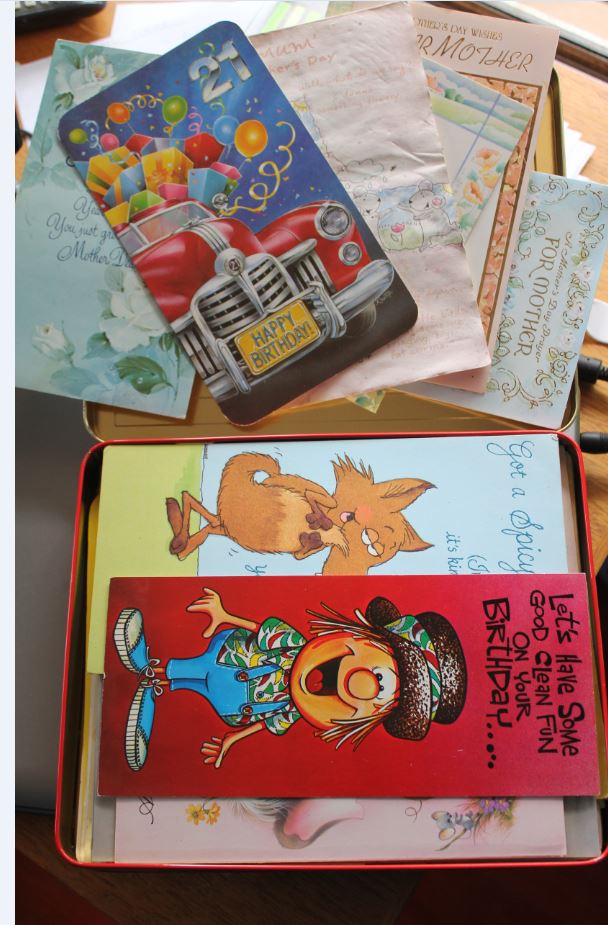

I was very excited to find a tin full of greeting cards dating back to the 1960s at an 80 year old aunt’s house recently, and was even more pleased when she said I could have it. But they are not even cards for our family! It turns out she bought the tin at a fleamarket and found it full. She had not kept her own cards so decided to keep these instead.

In the 2000’s, we were told as a museum to pick a theme which was relevant to our region and made sense based on our exhibits. We could be a transport museum, for instance, or an agricultural museum or a culinary museum – but we couldn’t be a folk museum. The state was overloaded with folk museums which were random and lacked a pulling factor for tourists. Museums are not storehouses of old things, they are participants in an active tourism trade and have a role in bringing trade to their local area. Once you know what sort of museum you are, you know what to accept and what to reject.

In a way, a family has the same task. Of course our theme is clear: what we keep is what pertains to the family. Just like a museum, most families are not simply storehouses of old things. The average non-genealogist will have some objective or objectives in mind when keeping family heirlooms. Perhaps to remember and respect their forbears, or to remind the family of its place in society, or maintain a link with a geographically distant culture. No need to be too clinical about this. Anyone who is thinking about their family history already doesn’t need to spell out the reason, but we do have a role to play in anticipating the more sceptical. In a lot of families there are sentimental dreamers and the more prosaic doers. Clearing out an old house is usually the task of a doer. They need to be well versed in what has value and ought to be kept even if no longer usable or needed.

The next thing we were told in the museum, was that an object, however old, however interesting, is really of no historic merit without its story. I tend to push this point in my blog entries because it makes so much sense to me. This is of exceptional importance when considering our family heirlooms. Some of us have an innate sense which tells us that this object is part of us and no reason is required. I love people like that. But many many people, who at some point will be faced with the decision to keep or throw, need a very compelling argument to keep.

Now, being able to say “That chair belonged to my grandmother’ is in fact a story. That’s all you really need for someone else to attach that value to that item in their own mind. They’ll remember that it was Grandma’s chair and think twice before throwing it away.

What about “That chair was a wedding gift to Grandma, made for her by her father who emigrated to Australia in 1875. It is a replica of the dining chairs his parents had in their home in Somerset. He even made the nails himself.”

With a story like that, the chair is even safer in the family. If there is a photograph of the chair with the grandmother or great grandfather, it is probably guaranteed to be passed down to someone who appreciates it.

Documentation makes a great difference as it proves a story, a fact well understood by genealogists. It holds equally true for family heirlooms. If you have a family heirloom, it’s worth taking a photograph of it with a family member. It helps to confirm its place with the family, it might keep that item from the tip in another fifty years time. You might not have a photograph with the original member, but young Lucy sitting on her Grandma’s chair in 2014 will still be a very valuable family item to Lucy’s own grandchildren, one which bridges the gap of eight generations if the full story is known – from the family in Somerset to Lucy’s grandchild viewing the photograph.

This is where a family differs from a museum. We can – personally I think we should – add our generation’s chapter to the story of each item. Its importance and its interest grows with each new event.

How we ensure the story passes along with the object is trickier. A book about the family helps. The story could be written on the back of a photograph, placed in a photo album, written into a will, explained in a family newsletter, entered into a family tree accessible to all which continues to be accessible after the tree’s creator has passed on. We could simply tell the story so many times that it is never forgotten.

How it’s done doesn’t matter, just so that when an old house is to be emptied of stuff, there’s someone to say “Make sure you don’t throw out Grandma’s chair. I’ll take it if no one else wants it”.

If this happens, the job has been done well.