My tree is full of strong women. Women of courage, ingenuity and independent thought who presented this trait in a multitude of ways. I’m very proud of them all, so I had to look hard for one who truly stood out to write into this week’s blog. And here she is!

My great grandmother Alice Head

Alice was born in London in a working family amidst overcrowding and industry. As a young adult, she emigrated to Western Australia and made the rugged journey from Fremantle to the very wild frontier mining town of Kalgoorlie. Here she met and married a young gold miner and they moved even further from civilization to an outback settlement. She learned to shoot a rifle, to ride camels and to cope with many privations. After her husband died in a mining accident she and her seven year old son stayed in the isolated settlement where she ran a boarding house. She eventually remarried and moved with her new husband to Leonora. Later they retired to Nedlands.

Her story is too big to tell in one blog post, so I am writing it in parts. I am using Part One for the Week 10 prompt.

Eucalypt which can be found in Western Australia. Eucalyptus leucophloia habit By Mark Marathon (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

In the various UK census records Henry has the occupation of gardener. Henry and Annie were married in 1871 and after a few years of shifting around moved into 10 Wigan’s Cottages in Mortlake in about 1880. Wigans was a large company with hops and breweries in many locations around London and a lot of residents in that row of cottages were their employees.

Alice’s mother Annie was a laundress. Even as recently as the 1880s women only worked if they needed the money, so most likely the family struggled. In the 1881 census Alice and her three elder siblings (Annie, Mark and Florence) attended school while her younger brothers Henry and Walter were still at home. Also in the family were Alice’s grandfather George Doo, and her uncle William Doo. It was a very full household for what was probably a very small house.

Jumping forward ten years to the 1891 census, the Head family lived at 61 Alexander Rd in Richmond. The house is here on Google street view but copyright prevents me from posting an image in my blog. It was a three story narrow brick terrace house in a world of seemingly endless brick terrace houses just like it, streets and streets of them all around.

Neither George nor William Doo were with them, although both were still alive and living nearby. Fifteen year old Allie was now working as a domestic servant and was the eldest child at home. Six younger siblings were in the household. The second youngest child was two year old Edwin, crippled from birth.

Perhaps Alice’s childhood world was something like this but with more siblings around and more fog and rain? ‘The Laundresses’ .Albert Edelfelt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/99/Albert_Edelfelt_-_Pesij%C3%A4tt%C3%A4rien_%281893%29.jpg

Emigration schemes had existed in England for hundreds of years, sometimes falling out of favour then, it seems, back when the need arose. In about the 1880s the United British Women’s Emigration Scheme (UBWE) formed. The scheme was managed by a team of charitable women in partnership with some churches. The operation involved vetting suitable women, then chaperoning them to their new colonial home and ensuring that they found work, generally as domestic servants.

The requirements were strict. The women were to be single, aged between 18 and 24, sober, respectable, Christian, with some education and with some experience of domestic work.

Domestic Work 1880s. Religious Tract Society pamphlet

The UBWE annual report (June 1896) says their London office that financial year had received 1666 applications. Of those applications they interviewed 1300. Among those applicants were Flo and Allie Head. (1)

A public talk in April 1896 described the scheme to interested listeners. (2)

During the ten or twelve years of the British Women’s Emigrant Association’s existence, emigrants, averaging 700 or more annually have been befriended and happily placed in the Colonies, either in Canada, South Africa or Australia … in Western Australia, women are still at a premium. A very lively description was given by Mrs Shaw of the rough travelling in those remote districts.

An article in Pearson’s Weekly further describes the scheme:

I have received a letter … from the secretary of the United British Women’s Emigration Association, in which she requests me to inform my readers that they are on the point of arranging for the passage of fifty domestic servants to the Antipodes. The cost of the journey is, I am given to understand, defrayed by the colony. Moreover, no repayment is required for this. In return the girls are expected to become parties to an agreement by which they undertake to remain for one year in Western Australia, their wages to commence on the date of their engagement in the Colony. It is not an altogether uninteresting fact that of the last party taken out under the auspices of this association, every single member had obtained a situation within an hour and a half of her arrival. … Wages in Western Australia commence at 40 shillings a month. Only girls over eighteen, who can be recommended, will be accepted, and those who wish to apply must do so with as little delay as possible at the London offices of the association.

Flo and Allie Head met the requirements, gave notice at their current places of employment and packed their bags. Flo was 20, almost 21, and Allie was 19. It must have been an exciting time.

The girls each year traveled with a matron who was employed by the Association. Miss Mary Monk was the matron to Western Australia. She journeyed every year, taking the girls out and returning alone to prepare for the next batch.

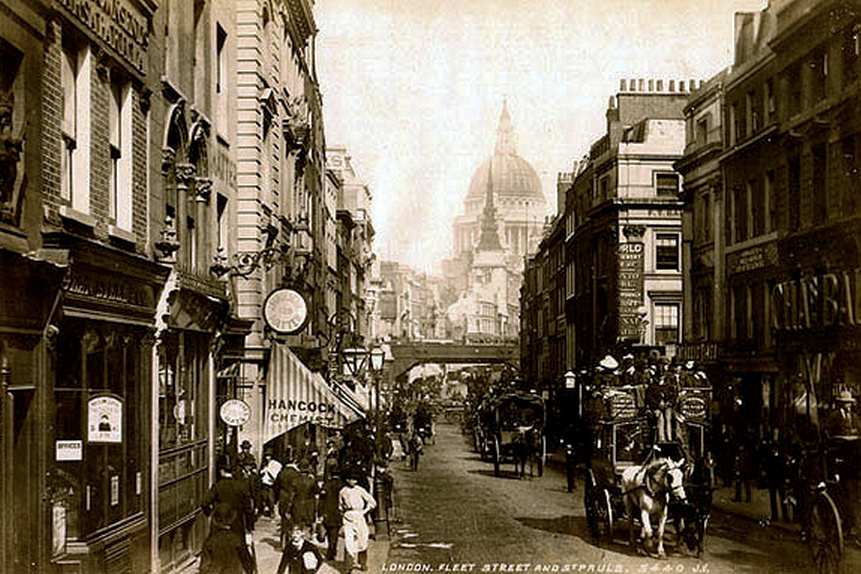

I spent ages looking for an image of the ship on which they were booked for the journey. The Steamship ‘Port Phillip’ has a name which makes it very difficult to search. Instead, I’ve found a public domain image of London at the time that Flo and Alice would have travelled through, heading for their ship.

Fleet Street in London looking east towards St Paul’s Cathedral. Photograph by James Valentine, c.1890. Public Domain in some countries including Australia but not in all. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fleet_Street._By_James_Valentine_c.1890..jpg

They departed on 17 Mar 1896, so embarkation was probably the morning of the same day or the afternoon of the previous. The whole family may have come to the wharf to see them off.

It is interesting to note on the ship’s papers that the ‘Port Phillip’ was legally licensed to carry 50 Statute adults, exclusive of crew, officers and Cabin passengers. Yet on this journey they were carrying 57 Statute adults. The journey was expected to take 85 days. Captain James Smith was in charge.

The girls traveled steerage and their matron, Miss Monk, had a cabin.

On the day of departure, the shipping lanes were congested due to a massive gale in Ireland preventing ships from approaching on their usual runs. In fact, there seem to have been bad gales right across the British Isles on that day. The girls would have been battling the wind as they walked up the gangplank onto the ship at Gravesend.

There is only the briefest mention of the Port Phillip in the shipping news.(4)

GRAVESEND: Tuesday, the Lusitania, from Bermuda, and Ovingdean Grange, from Buenos Aires, passed. The Carthage, from Bombay, passed. The Illovo, from Port Natal, passed yesterday. The Umbilo, for Port Natal; Warrigal, for Sydney; and Port Phillip, for Fremantle &c; left.

I’ll leave this post here, with Flo and Allie sailing away from the densely populated world they had always known for the unknown.

But to conclude, because I love lists of names, I’ll add the passenger list. My transcription just has names and ages. The actual shipping records contain more information. But it is still interesting to see all the girls.(5) Flo and Allie probably became very friendly with at least some of them.

Passengers under Miss Monk on the Steamship ‘Port Philip’ departing Gravesend on 17 March 1896. Page One.

Passengers under Miss Monk on the Port Phillip departing Gravesend on the 17 Mar 1896. Page 2.

(1) Woman’s Signal 25 June 1896 ‘Habitual Sobriety’ p. 6

(2) Western Times 14 April 1896 ‘District News’ p. 6

(3) Pearson’s Weekly 01 February 1896 ‘Let It Be Known That’ p.4

(4) Dundee Advertiser 18 March 1896 ‘Mail News’ p.7

(5) UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 via Ancestry.com.au

Interesting information, quite a change of scenery from London to isolated WA.