Warning – this post is a bit grim and graphic in places.

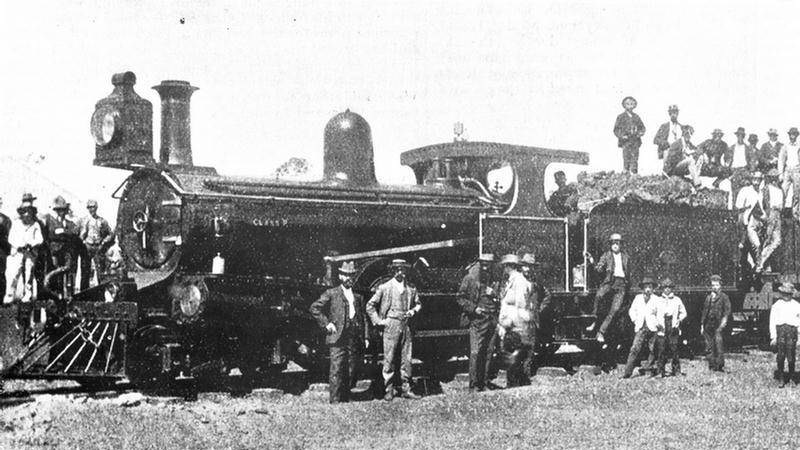

Douglas James Brown of Bothwell, Tasmania enlisted in Maryborough, Queensland under the name of John Brown. He served for 22 months in a battalion which fought on the front line at Gallipoli, Egypt and France. During his service period, Doug aka John Brown received no injuries requiring hospitalization. He was promoted to the rank of Corporal while serving at Anzac Cove. On 25th July 1916 at Fromelles, France, No. 568 Corporal John Brown was killed in action whilst participating in a planned operation against the enemy. His name can be found on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial in France .

Unfortunately I have no photo of him.

Near Bothwell, the home environment of Doug Brown.

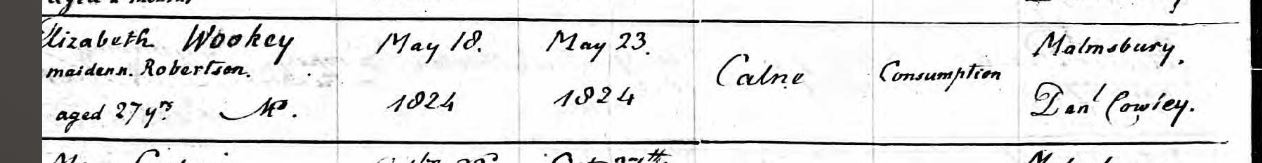

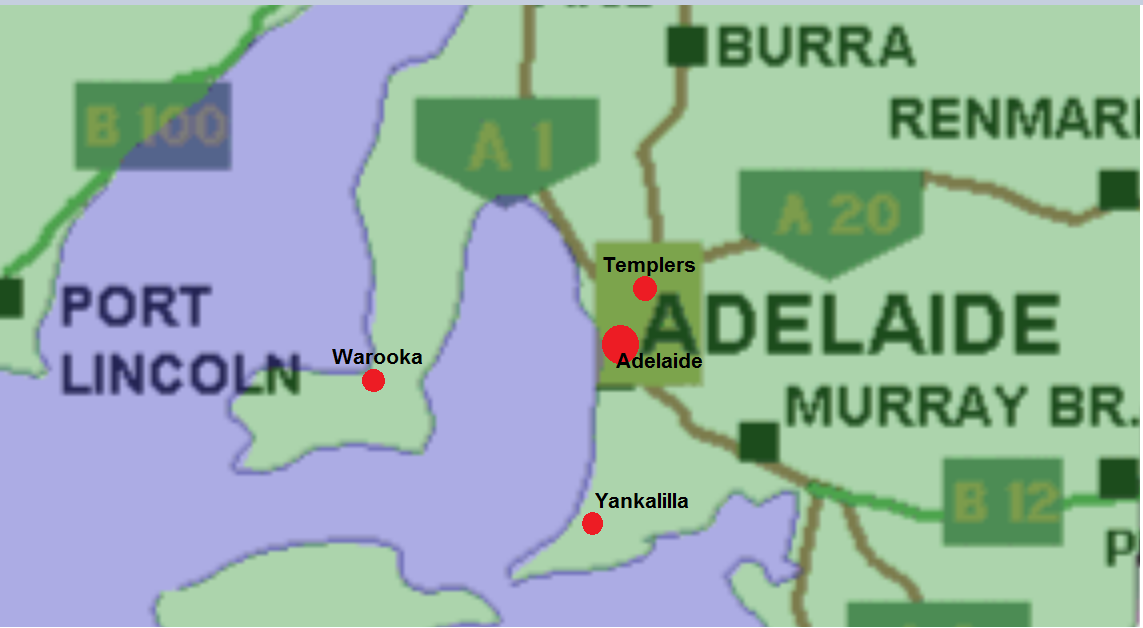

Doug was the third of nine children born to John Brown and Sarah Ellen nee Cox. Born on 18th March 1887 in Bothwell, Tasmania, he was known as ‘Jack’ or ‘Doug’ to his family. His father was a farm labourer and the family moved often between different properties in the region. On 14 Feb 1900 when he was thirteen, Doug’s mother died of postpartum haemorrhage. His father later married Esther Cox, sister to the deceased Sarah. Three children were born to John and Esther.

Doug was close to his elder sister Esther who married a widower with two children in 1903, and he was a strong influence on Leslie and Doris Reading, his new step-nephew and niece.

Doug’s father could not read or write but the Cox family including his mother and stepmother were literate. Doug and his siblings could read and write, but there is no evidence of formal schooling. In adulthood, Doug became a blacksmith.

Doug volunteered with the pre-war 93rd Derwent Regiment in New Norfolk, Tasmania, where he served for 18 months. This was probably part of the compulsory youth training which occurred in Australia at that time. He was joined there by his nephew Leslie Reading . Jack then left the 93rd Derwent Regiment in order to move interstate.

Enoggera Army Camp 1914 By Poulsen, Poul C., 1857-1925 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

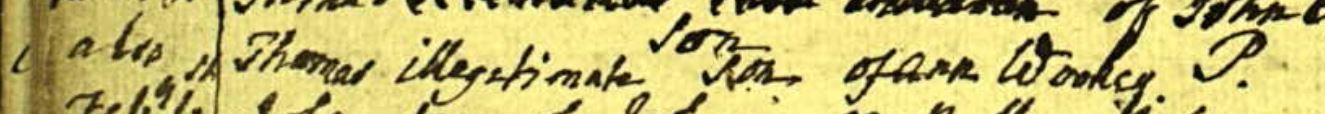

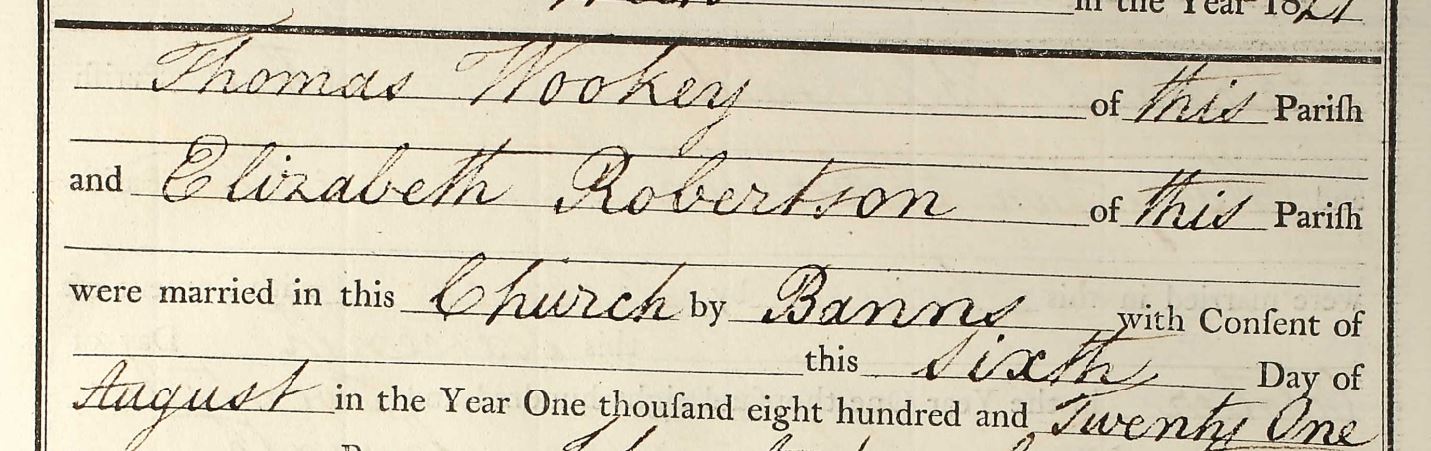

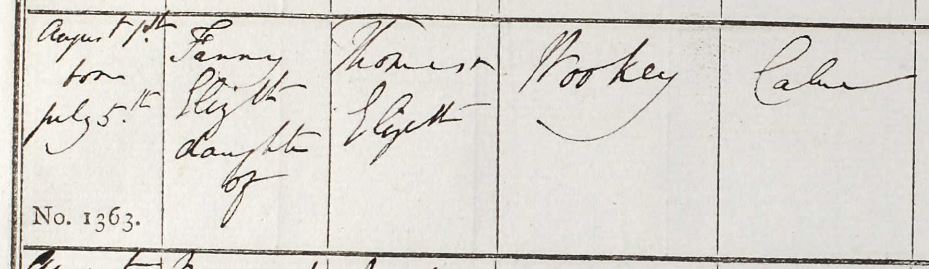

I’ve lost sight of his movements between his leaving Tasmania and the date of his enlistment. But he ended up at Maryborough in northern Queensland. Recruitment for the newly created 9

th Battalion Infantry opened in August 1914 and Doug signed up at once. Recruitments were underway for both the Expeditionary Force and the regular infantry. After attestation and a medical inspection, the new soldiers were all sent on to Enoggera where they undertook the rest of the formalities.

In his attestation papers, Doug stated he had never married. He was 26 years old, weighed 144 lbs and was 5 feet 6 inches tall. He was brown haired, brown eyed and his complexion was fresh.

On 30 September 1914, Doug’s nephew Leslie Reading joined the 15th Battalion in Hobart, Tasmania. Leslie’s enlistment was against the wishes of his family. Throughout the war, Doug seems to have felt some responsibility for Les.

After three weeks at Enoggera the 9th Battalion embarked at Pinkenbar on the HMAT Omrah for Melbourne. It was a quick process. Lieutenant Colonel Harry Lee was the commanding officer. The commander’s war diary reports

Embarked during morning and sailed at noon. Weather fine. Stats: 32 officers, 999 other ranks, 15 horses

HMAT Omrah (A5), with the 9th Battalion aboard, lying at Pinkenbar on the day of embarkation.Black & white – Glass original half plate negative. 24 September 1914. Public Domain via Australian War Memorial website C02481

Training began immediately. The men were allocated emergency stations and on the three day journey to Melbourne they undertook fire drills, bomb drills and inspections. The war diary reports:

25.9.14 Told men off to five stations. Heavy swell. Many men seasick.

They reached Melbourne on 28th September and anchored at Williamstown. No shore leave was granted, but the men disembarked most days to undertake marches. In October they shifted into barracks at Albert Park where training became more intense. After a final inspection by General Bridges, the troops embarked again on the Omrah.

Stats: 32 officers 986 other ranks

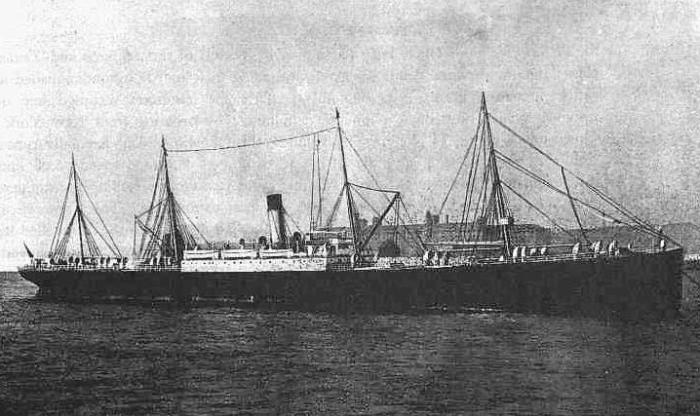

HM OMRAH By B. Jefferson (Australian War) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

This was a journey of five days. They anchored in King George’s Sound near Albany, Western Australia on 24th October 1914.

On 25th October the medical officer reported a case of measles. Just one. The soldier was transferred to an onshore hospital. Training continued for the rest of the men. The training exercises had names such as ‘musketry’ and ‘enemy in sight’. On the 1st November, they left Albany. This was the real thing at last for this battalion.

The training continued on board. ‘Enemy in sight’ and ‘Sinking Ship’ are exercises referenced now. The men probably didn’t know where they were going, but they would have realized they were leaving Australian waters.

9.10.14 Message from HMAS Melbourne re ‘Sydney and EMDEN’

This brief entry was regarding the sinking of the German military ship ‘Emden’ by the Australian ‘Sydney’.

On 15th November the HMAT Omrah reached Colombo, giving Doug his first glimpse of foreign lands.

16.10.14 4.30pm Received from HMS ‘Hampshire’ 2 officers, 2 warrant officers and 40 ratings off EMDEN

16.10.14 Colombo Placed prisoners under armed guard. Capt. MELBOURNE 9th Infantry placed in charge of prisoners.

The November diary is missing so I don’t know how they spent that month, but by 2nd December they gave the prisoners back to the HMS Hampshire in the Suez Canal.

04.12.14 7am Arrived ALEXANDRIA. 39 Rank and file sent to hospital with measles.

The Battalion reached Alexandria on 4 Dec 1914 and marched to Mena Camp. The first job upon arrival at camp was always to build it. The next few weeks were spent digging and erecting structures.

Colonel Ewen George Sinclair-MacLagan was present with the 9th Battalion from August 1914 and would have been a familiar face to Doug by this point, as were Captain Salisbury and Major J C Robertson. The war diary shows that all three officers remained very involved with leading and training the rank and file of the 9th Battalion.

9th and 10th battalions in Egypt in December. Doug may have been one of the men in this picture. Australian War Memorial C02588 Public Domain Lent by Chaplain the Reverend E Merrington Australian_9th_and_10th_battalions_Egypt_December_1914_AWM_C02588 via Wikimedia Commons

Christmas Day was spent at Mena. Gifts were distributed to the soldiers.

Across that week between Christmas and New Year, three men died of pneumonia. Six men were sent back to Australia as being ‘ incorrigible or medically unfit‘.

Oh how they trained. Every day they performed exercises, marched, conducted drills. The following two diary entries are the most relevant in this month.

09.2.14 Reinforcements joined. Strength 32 officers, 1039 Other ranks.

28.2.15 MENA Received orders to move. Strength 1081 officers and men. 63 horses. In hospital – 34, In detention – 1, Absent without leave – 8, Effective – 1038

The troops marched to Alexandria and boarded the HMT Ionian. Then one soldier – Pte J M Davenport – was found with his throat cut. He was transferred to hospital where he later died. It’s the first indication of fear in the ranks. There was no inquiry held so they must have believed it to be self inflicted.

After a three day journey, 9th Batallion arrived at their new camp on the island of Lemnos where they built their camp, a road and a landing stage. Doug’s first surviving postcard home was sent from Lemnos to his mother in early April.

ON ACTIVE SERVICE April 1915

to Mrs E Brown (From Greece)

Dear Mother,

A line or two to let you know I am alright. I saw Les the other day, he is quite well. Remember me to all.

D Brown

Anyone with a basic knowledge of war history will know what is coming, but of course Doug and the rest of them did not. Up until 8th April it was business as usual for the 9th Battalion.

Two relevant diary entries:

8th April 1915 LEMNOS BAY Embarked on MALDA

21.4.1915 6.30pm Received Brigade inspection order.

I learned through reading the diaries that an inspection precedes action. Things were about to happen.

On 24-25th April 1915, the 9th Battalion made history by being the first Battalion ashore at Gallipoli, where they unfortunately landed two miles further up the beach than intended. The whole campaign is graphically described in the war diary but it is very long. I’ll pluck out the relevant bits.

24.4.15-25.4.15 11am . Transferred A + B Coy and Hd 2is Staff to QUEEN steamer slowly to KABE TEPE. C&D Coy travelled per transport MALDA and transferred to KESTRIAN en route. The QUEEN arrived off KABE TEPE at midnight and transferred into lifeboats 1am.

The 3rd Brigade supplied the arriving party which consisted of two Bg from each Bn. The remaining two Bgs landed half an hour after the convening and were to act as supports. It was decided to land just North of Kabe Tepe. A Co. on the right and land packs were to be discarded and at trench resupplied. A & B Cos were to take the truck and afterwards to attack a Bty of guns on Kabe Tepe. The Life Boats towed by a Pinnas(?) moved slowly towards the shore and it was apparent that the N? people has …. keen direction. It was discovered afterwards that we were two miles north of the position intended. The landing was effected under rifle fire and the transfer pressed forward. The enemy gave way and the advance continued. Turkish reinforcements se.d the rush and our troops were driven back and hastily entrenched on a commanding parter.

Turks attacked again about midnight but were repulsed. The Australians displayed great bravery and held on tenuously. False orders were issued by ..? officers. Attempts were made to reorganize the 3rd Brigade 100 men and 7 officers mustered. The Bn detailed at dusk as covering party for troops entrenching Major J C Rokesbon, Captains Miler, Jackson, Ryder, Fisher, Melbourne. Lieuts Chambers, Paterson, Jones, Brasic, Hounded, Major SB Robertson, Lieuts J Roberts, Heyward, Costain and Rigby killed.

26.4.15 Gallipoli Whole Division considerably mixed, under heavy rifle and shell fire all day and night, all heavy digging is under fire. Further attempt to reorganize Bn about 1000 3rd Bn … remained above beach till 1pm. Bn started as No. 2 … of defence under Col MacLagan Lieut Kev launched.

27.4.15 Strong attack by Turks at 10.30 repulsed

And on it goes, relentlessly, day after day, week after week. There was no break at all for these guys. Every day the diary is full of new dead, new attacks. There was no advance. They held ground, mostly, and their enemy did the same.

13.5.15 Continuous snipering. 1 killed 1 wounded. Total casualties killed 45, wounded 286, missing 179, sick 20. Water Barge sunk with 5 days water supply by shells.

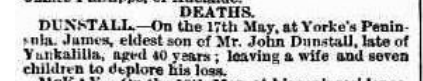

Doug survived. His nephew Les Reading in the 15th Batallian lost his life in the first charge and was reported missing on 27th April 1915, but Doug was clearly not aware of this.

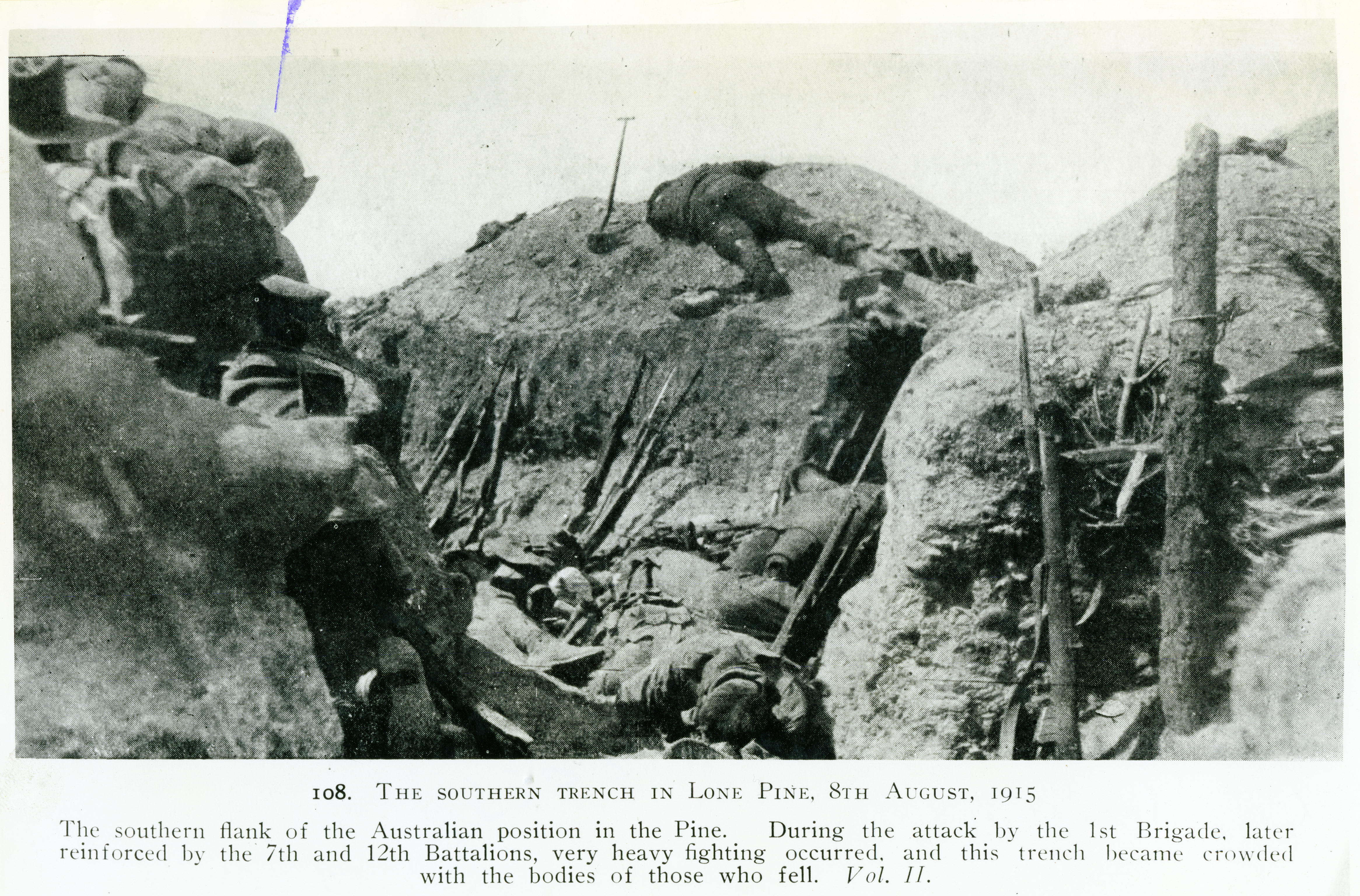

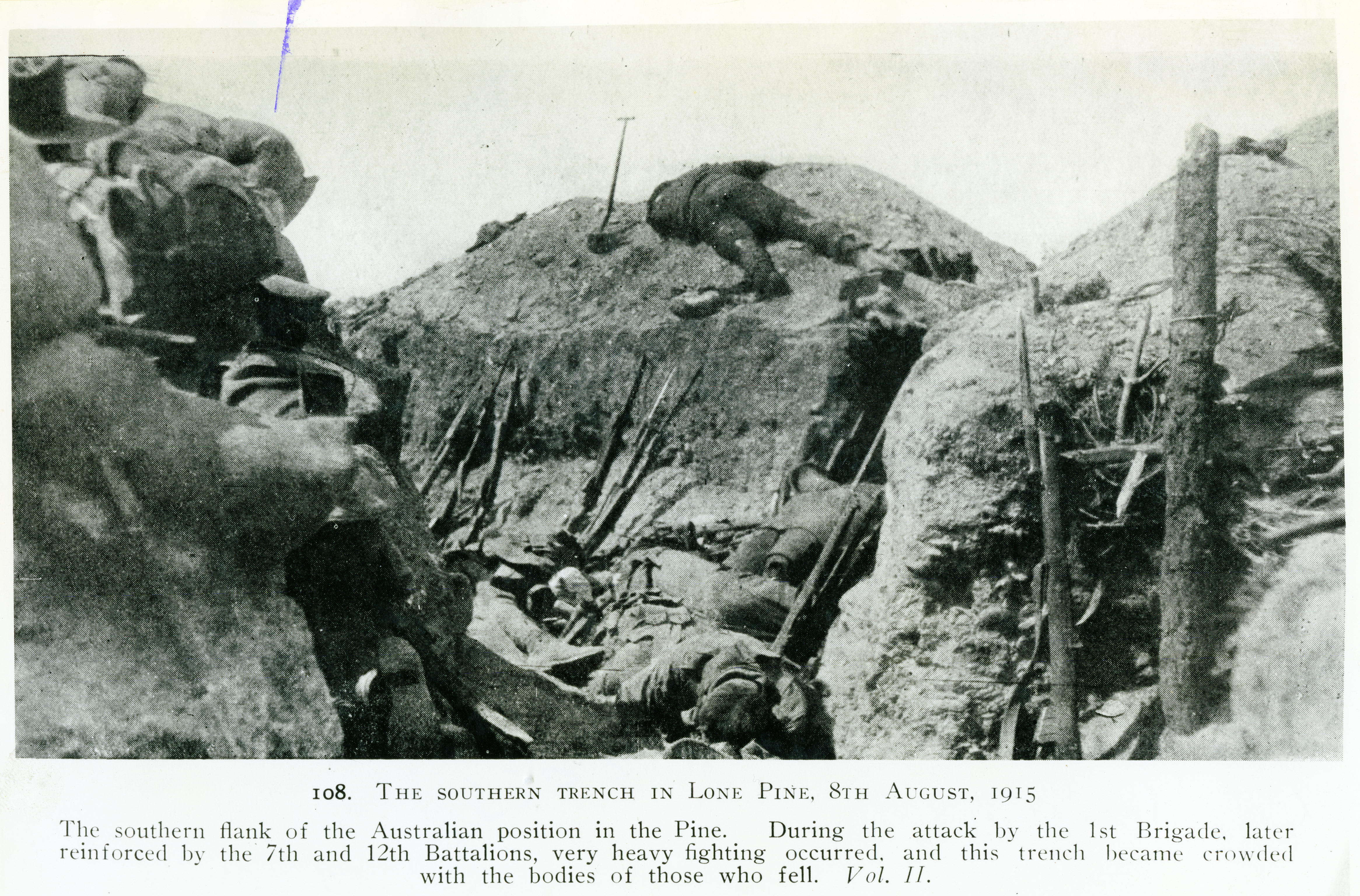

A hard hitting photo of Gallipoli. This is what Doug was seeing. Southern Trench in Lone Pine, Gallipoli, 8 August 1915 Archives New Zealand from New Zealand – Southern Trench in Lone Pine, Gallipoli, 8 August 1915 [Graphic Content] By Archives New Zealand from New Zealand [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

19.5.15 Heavy attack by the enemy about midnight repulsed and a renewed attack at 3am. Enemy advanced in close order and some reached our wire entanglements. At 8am the enemy’s infantry had been driven. A heavy bombardment of our trucks took place until noon. Casualties 16 killed 25 wounded. Word received in the evening that more large Turkish transports had landed troops.

20.5.15 At 7pm enemy advanced under cover of white flag and stretcher parties and attacked. Attack lasted till 8pm. 205 Turkish dead counted in front of our position within 150 yards. Many were on the forward ridge. Killed estimated 3000 with total casualties 7000. M G Section, 8th Light Horse attached to 9th Bn.

I’m skipping a lot of entries of similar ilk. Even with all our movies and books about this time it is hard to get a feel for the true ordeal. I came closer, reading the handwriting of a man who was in the thick of it. In this month Colonel Lee was injured and Major Salisbury took charge.

31.5.15 Major Robertson returned to duty and took command. Strength 835 other, 19 officers no casualties 6 sick. Two were wounded.

The 9th Battalion spent six months at Anzac Cove, a time of constant shelling, sickness and bad weather. One postcard survives from this time, dated 8th June 1915.

ON ACTIVE SERVICE 8th June 1915

Dear Mother,

A few lines to let you know I am quite well. Have not seen Les lately. We are some distance apart. Hope to see him soon. Hope this will find you all well at home, it is summer here and very warm at times. Can’t get writing material at present.

D.B.

We know now that Les was deceased. His body had not been recovered and at about this time the family were informed that he was missing.

Australian troops charging a trench at the battle of gallipoli. Public Domain via Shutterstock Photo via Good Free Photos

Further selected entries:

28.6.15 No. 551 Pte J Holloway and No. 1533 Pte J Dowd reported on for meritorious service. Major Walsh and Capt L Jones wounded, latter seriously. Lieut Jordan missing. The missing in B. Co. now almost certain to be killed, it is possible that of the 15 missing in C Co, the party under Lieut Jordan, may be prisoners.

29.6.15 Major J C Robertson appointed Lieut Col whilst in command 9th Bn to date from June 1st. D.O. No. 11 No. 68 dated 28th June 1915. Arrangements made for parties for recovering dead upset owing to a demonstration against enemy. Secured five bodies early this morning, shipped off boots and clothing.

7.7.15 23 officers and 368 NCOs and Men are now away at the base wounded. The bulk of these have been away over two months. The Bn has secured no word of their condition, whereabouts or likelihood of return. Extension of Y tunnel commenced.

23.7.15 Three cases lately of men cutting off or shooting off fingers the intention being to get sent to hospital. Case occurred today and arranged with … ambulance to keep the man at ANZAC instead of sending him away. Owing to suspected attack men stand to at the waning of moon and daybreak.

On 12th August 1915, Doug was promoted officially to Lance Corporal.

27.8.15 Effective strength of Bn reduced to 21 officers and 598 other ranks owing to sickness. Finished up new firing line now building forward bomb pits and entanglements.

Finally came a day they must all have been waiting for. The end of their scheduled period of active service.

25.10.15 6 months service in firing line completed.

Strength of battalion 19 officers, 536 other ranks including MO Wounded and missing still absent 11 officers 372 other ranks. Total casualties since 25.4.15 – 43 officers 1357 other ranks including 9 officers and 142 other ranks killed, 1 officer and 72 missing, 15 officers and 462 other ranks wounded, 18 officers and 661 other ranks sick or injured.

They were still at the front, but their activity began winding down.

29-30.10.15 Both days quiet. On morning of 30th handed over from T6 to Q1 to 1st Inf Bde Composite. Co. disbanded and returned to reinforcement camp. The Bn is now holding from Q1 to Q4.

31.10.15 Quiet. Nothing doing. Completed new snipers dump fort. Strength of Bn 17 officers, other ranks 498, total 515

The record of losses seem pretty dire, but the battalion had received reinforcements twice during that time. Of the original 1038, they were actually down to about 200. Doug was one of those.

Finally:

14.11.15 At 1000 the 2nd Bn (Lt Col Cass) took over our lines. Bn went into Bivouac on W of Artillery Road. At 1800 received orders cancelling embarkation of Bn.

I can’t imagine how they felt having embarkation cancelled like that. But it was only a delay of two days. When the orders came through it was a mad rush.

16.11.15 At 1800 received orders for Bn to be ready to move in 15 minutes.

16.11.15 Marched out of bivouac at 19.30, embarked from no. 8 pier for S S Abassiah.

17.11.15 LEMNOS. Disembarked at Mudros at 1000 and marched to Sarpi Camp.

And just like that, they were gone from the front, weak, sick, traumatised and exhausted. It should have been a move for the better.

From the collection ‘Photographs of the Third Australian General Hospital at Lemnos, Egypt & Brighton (Eng.)’ / taken by A. W. Savage 1915-17. via NSW State Library.

Another postcard from Doug. This must have been over two cards but the first one is missing. He is clearly talking about Les and still does not know that Les is missing.

Mrs E Reading

From Greece – continuation

… but it is a wonder I have not seen him. I dropped you a PC to your old address a few days before this so you may get the lot at once. Goodbye from your ever truly brother D Brown

Things were better in one way, but not in others.

18.11.15 Absorbed 8th reinforcements. Began reorganisation of Battalion.

19-24.11.15 Bn employed in easy preliminary training. Weather very rough and cold.

They were tottering wrecks of human beings at this point and the commanding officers knew it. This was a time of attempted recuperation. Were it not for the weather and lack of supplies, it might have worked.

24.11.15 Lemnos Busy arranging camp. Bitterly cold weather.

26.11.15 Remaining units of Brigade arrived this afternoon. Bn had route march two miles. Cold gales blowing making work difficult. Men feeling the want of warm clothing.

27.11.15 2nd Lieut Gray rejoined. Snow falling. Arranged for purchase of 200 pounds of comforts for men from Store ships. Short route march and organizing.

30.11.15 Lemnos. Squad drill under squad commanders from 1000 til 1200. NCOs class in the afternoon. Shortage of blankets remediated. Arranging an entertainment committee for men.

01.12.15 Lemnos. Building stone wall to protect cook’s lines. Whole camp placed in quarantine owing to outbreak of diphtheria.

They couldn’t catch a break, these guys. But this was the lowest point.

7.12.15 Rifle exercise. Marked improvement in health. Bn becoming much stronger physically.

Highly successful entertainment by NCO and men of 9th Bn in YMCA recreation tent. Items most respectful and topical of ANZAC and Sarpi quarantine camps.

Doug sent a postcard home in mid December.

ON ACTIVE SERVICE

Mrs E Reading

Just a PC hoping you are and family are quite well and that this PC may find you. I am in good order and still kicking and be back for a good time for next XMAS I hope.

Yours truly,

Brother (D Brown)

Doug spent Christmas 1915 at the camp at Lemnos. The Battalion received orders to move on 31st December.

But since we are only halfway through Doug’s war experience and this is a long blog, I’ll leave it here.

Doug was later promoted from Lance Corporal to Corporal and was positioned at the front in both Egypt and France. He was killed in action in France on 25th July 1916 while taking part in a large scale operation that went horribly wrong, resulting in the deaths of 393 soldiers. Had he survived that day, he would probably have survived the whole war.

His belongings and medals were sent home to his parents, who also requested a photograph of his grave.

His death, and that of his nephew Les, had a big impact in the family. Both soldiers are still remembered by the family to this day.

Bibliography

Diary Excerpts from: Australian Imperial Force Unit War Diaries of the 9th Battalion, AWM4 Subclass 23/26 – 9th Infantry Battalion via Australian War Memorial website, accessed 25 April 2018.

Grave Registration Report, Commonwealth War Graves website, accessed 25 March 2018

Lt. Col J C Robertson, ‘Report on operations carried out by 9th Infantry Battalion Commencing 19th July’, insert in the War Diaries 9th Battalion July 1916

Family postcards and letters