Our road trip was drawing to a close now. We slept at a relative’s house in Wangaratta on the sixth night and had the car packed and ready to leave by seven thirty the following morning. The plan was to view my grandfather Ken Dunstall’s grave in Birchip, and explore some new roads along the way.

Wangaratta to Benalla to Shepparton was a road already travelled. This time at Shepparton, we needed to go to Echuca. We’d learned about Shepparton now and forewarned is forearmed. We’d printed a map with google road directions and we followed it closely. Without too much stress, we found ourselves on the road in the picture above.

I don’t have much family history from this region. We drove past fields full of hay bales, it still being the middle of harvest, and grain trucks were all around. The signage was excellent. As my son pointed out, there’s always a sign to Echuca from every direction. We reached the rural city of Echuca by 10:30 AM.

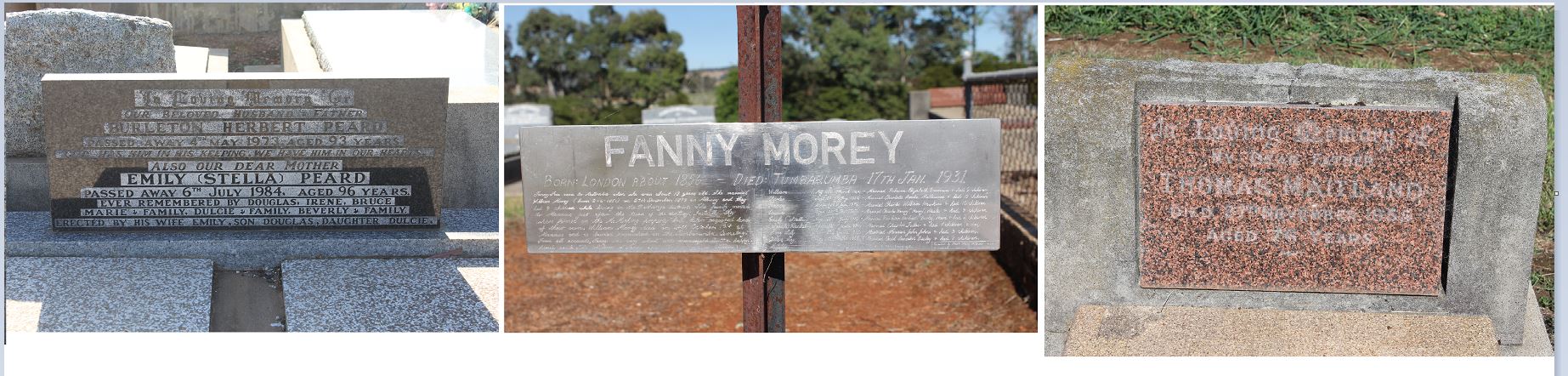

It occurred to me coming into town that my husband’s grandfather might be buried in Echuca. The man was somewhat estranged from the family and ended his years living in a caravan in one of those little twin-towns that exist all along the Murray River. I wasn’t quite sure but I thought Echuca was the one. I sent a text to my in-laws and while I waited for a reply, we went straight to the cemetery.

Echuca was a very nice rural city. Well run, full of helpful people and most magnificently signposted. You notice these things as a traveller. Clean public toilets everywhere, park benches along the river, friendly people. I asked for directions to the cemetery in a post office on the south side and started a conversation between all customers and staff on the best way to get there. I always enjoy these social moments with strangers.

The cemetery had staff onsite to look up their records and I learned very quickly that my husband’s grandfather was not buried there. This was a show stopper. I then received a text from the in-laws saying they didn’t know where he was buried and would ask my father-in-law’s sister. It turns out she did not know where he was buried either. Now, the plan is to ask the final sister.

Here’s a task for me. I was feeling pretty bad not knowing where my grandfather was buried, but these guys didn’t even know about their own father! It seems clear that neither attended the burial. That man is high on my list to introduce to his family now. I’m sure there were good reasons for the estrangement, but the man passed away at least twenty years ago.

We left Echuca at about half past eleven in the morning. West of Echuca the terrain changes. The farms are bigger, the land is flatter, the towns are further apart. We came into Cohuna a little after midday but did not stop. The plan was to have a late lunch at Kerang, some 95km from Echuca.

We were in Kerang by 1PM and enjoyed lunch there. It’s another beautiful little town, a decent size and with a lot of activity in the shops. After lunch we were ready for the challenging part. From here, we had to leave the Murray Valley Highway and head in a zigzag along a series of rural roads, in an area probably without mobile phone service. I filled the tank at Kerang just in case we became lost, double checked my directions and we headed off.

The towns we wanted were Quambatook, Towaninny and Dumosa, then to Birchip. We had some written instructions telling us where to turn right and left. We had plenty of time. We boldly set out, my son manning the direction sheet while I drove.

This was emu country. My son saw some but since I was driving I missed them. We knew they’d be there somewhere in the shrubby trees. There was very little traffic and the roads were long, straight and narrow. We had no trouble finding Quambatook. There were hardly any opportunities to turn off the road and it was signposted beautifully. It was a nice little town, seemingly deserted with an incredibly wide main street presumably filled with grain trucks at times. We stopped here to stretch our legs and didn’t see a soul.

There was a sign to Dumosa as we left town. This was encouraging. However, just out of town we struck a big hitch. Here it is: an intersection that google didn’t give us directions for – that had two options, neither of them a town we were heading for.

Swan Hill or Wycheproof? We had little time to decide with a truck coming up behind us, and each of us agreed on Wycheproof. From this time on, there was a little bit of stress while we watched for signs to Dumosa. There simply weren’t any. As it turned out, we were on the right road all along – I think – but there were no signs to anywhere. We never did see another sign to Dumosa and did not find Dumosa. We didn’t find Towaninny either, or a sign to it. What we did find was an intersection with a road number on it that we knew was correct, pointing to Birchip. From that point, we relaxed a little and enjoyed the very small rural road we were travelling on.

After 50km of narrow road, red dirt and open fields we saw rooftops in the distance, and suddenly we were in Birchip. Home of the Mallee Bull.

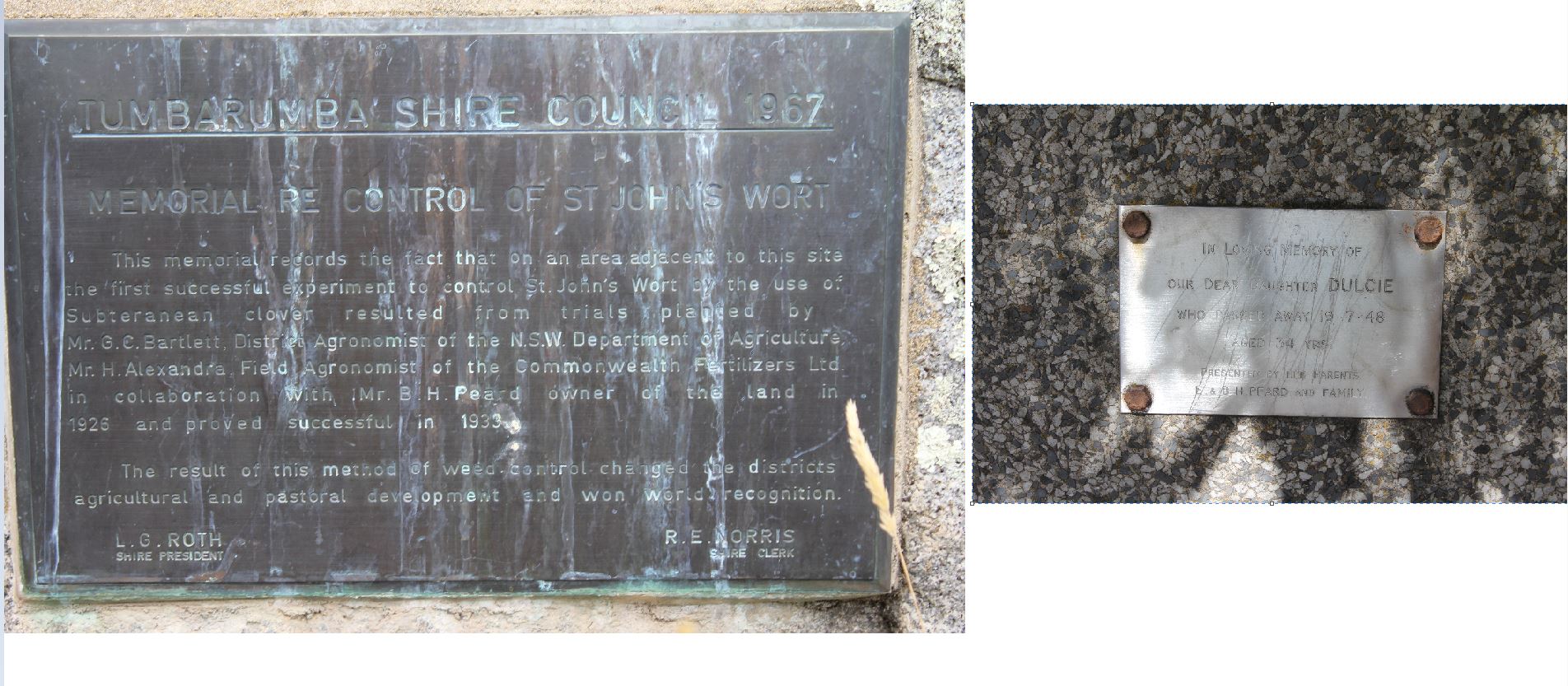

It was now about 4PM. I have posted my grandfather’s grave in the blog about Kenneth Dunstall, so I won’t repeat it here. Since it was still quite early, we headed for Watchem, the nearby town where my grandfather finished his days, and where the family still own a property with one house on it. I was very keen to see it.

Watchem was a very pretty little town, but it looked something like a ghost town. There were a few derelict buildings and a few empty service buildings. There were also some occupied, well maintained homes. It was a mix. We had to phone for directions to the house as the street it was on had no signpost. The town obviously has a long history and I’ll have fun researching it one day. In the meantime, we were beginning to feel weary after the day’s travel and were glad to find the house. Armed with a letter of permission from my aunts, I met the man who lives on the property to keep it safe and went to explore the house, seeking any clues about my grandfather. The family bought this house because it reminded him of his childhood in Western Australia.

Yes, it’s a mess. Since my return home I have conferred with my aunts and uncle and we have initiated some much required maintenance. It’s a lovely house and were it not for the cobwebs I would have enjoyed exploring the rooms. It must have been charming in its heydey, and if lived in again it would still look quite charming. However, it is beginning to fall down too. I found very few traces of my grandfather, but they might yet be in there. Instead of searching for signs of how they lived, we found ourselves making a rather clinical inspection of damage and danger areas, and identifying the various pests which were moving in. We also spoke at length with the occupant who told us of a few other issues.

I hope to make another visit at some point.

It was getting late. Since I had permission, I collected some likely tins and folders of papers to bring home with me. We left at about 6PM and headed for Dimboola which was a distance of about 90km. From here we were back on the familiar A8, the highway from Melbourne to Adelaide. We slept the night at Keith, and arrived home at midday on the eighth day.

This brings the road trip to a close. It was a very full week and a day of making discoveries and connections. Days later, I am still going over all I have learned, and getting to know my living relatives was a priceless experience. One day, I hope to do it all again!