#52Ancestors Week 2-Favourite Find

This week’s prompt for 52 Ancestors is ‘Favourite Find’. I have many, but I’ve not yet written about this family. It’s definitely time. Finding Patrick Dillon broke down a very persistent brick wall.

It also returned a lost surname to the tree. My paternal line is ‘Dillon’ and for decades we accepted that we had Dillon ancestry. Actually we didn’t – the paternal line is ‘Dillane’ morphed into Dillon quite recently. So after losing ‘Dillon’, a bit of research in a different line has brought Dillon back in a different place in the tree.

This is partly a post, partly a scrapbook of quotes by others about the world of Patrick Dillon, partly a historical account of Ireland from 1770-1800. I’ve done this to fill out his world where we don’t know about him personally. He lived in violent times and this is not a gentle history, but it’s accurate to his world.

Patrick was probably born in the 1770s, maybe in Dublin. He was Irish Catholic, which makes him hard to find, plus his name is very common. He was married in Dublin in 1803 and six children were born to him there. My ancestor is a seventh child to the family and there is no baptism record for her.

Dublin was a difficult place for an Irish Catholic to live. This post describes the events of the time, and how I think Patrick was impacted by them.

Irish Catholics in Ireland were into their third century of demonization by the time of Patrick’s birth. It’s hard to imagine what that does to a society, with successive generations stripped of dignity, respectability and hope. The goalposts changed regularly, they could never form a plan to pull the family together, no new way of life lasted more than two generations. And by the late 18th century they were seeing the effects of abuse on the land by the English overlords. Absent landlords ordered the planting of crops not suited to their soil, wars had resulted in the deliberate despoiling and salting of Irish owned land, as punishment. Whole forests were burned to the ground to prevent Irish soldiers and civilians from hiding.

It’s a grim picture, amidst which the Irish Catholic families fought for survival and justice, but also did what they could to lead stable, safe and happy lives. We still have remnants of their very hidden inner lives in songs, fabrics and devotions.

Plus there were wealthier Dillons: they were a major force a few centuries earlier and had found common ground with England. Many of them even became protestant. It’s possible that my Patrick came from Protestant origins, but in 1803 he was married in a Catholic church in Dublin and there’s no indication that he was comfortably off. He was most likely a quiet honest working man in the middle of difficult times.

Historian and journalist Philip Harwood describes Ireland this way:

The situation was different across Ireland. Organised action against the tyranny of the British in the southern half of Ireland tended to start in Munster – that is, Cork, Waterford, Limerick and Kerry.

Dublin was far more English controlled. This meant fewer privileges for the native Irish, but conversely more stable employment on English properties so more family security. If you could put up with the subjugation, living conditions were much better. And maybe the English officials here were able to relax a little and give the Irish tenants some of the perks of a free people.

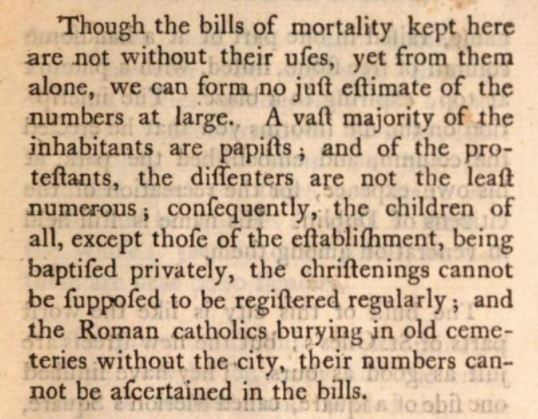

A man named Dr Thomas Campbell described Dublin in 1777 as an expansive city, about a quarter the size of London in area but with more empty spaces between the houses. A beautiful bay of blue water, a scenic coastline. He was surprised since England viewed Dublin as a smaller place, but noted that many Irish Catholics lived in Dublin who were not counted in any records.

Campbell describes Dublin beautifully, both the good and the bad. This is Dublin as Patrick would have known it.

Campbell visited Dublin University and wasn’t impressed at all. Then he spent a few days exploring Dublin beyond the main squares and began to see how people were living.

Campbell described the hospital in some detail, and how it was a centre of social life since the hospital actually held music nights and dinners and concerts and dances which were attended by many. They were, of course, for Protestants only.

He then tells us about the Dublin people and here we get a glimpse of Patrick Dillon’s cohort. (canaille is a French word referring to the beggars and homeless and downtrodden poor).

It’s inevitable that the Irish people would be like this, given their past and their present treatment and the complete inaccessibility of any infrastructure to assist them.

Campbell clearly understood this. He shows himself to be a very understanding man.

Alcohol was probably the only recourse for medication, for entertainment, for warmth, even for sustenance. It’s also the one thing the British people supplied very freely to the Irish folk. And in those days they didn’t realise it was addictive. But drinking was common among the Protestants too, with every daily occasion involving drinks. No wonder Thomas Campbell was disturbed by what he saw.

Not all Irish folk were alcoholics: just the ones who had given up.

Our Patrick hadn’t given up as he reached his adult years. He was young and most likely fit and hopeful. I think this because he got married and must have felt he was able to support a family.

Historian Philip Harwood describes Ireland in 1783 as a place ready for independence from England. Even the English colonists wanted this, so they could profit from exported produce, choose their own customers, set their own taxes and make adjustments that would help the population. Protestants and Catholics united more than ever before in this.

A lot of parliamentary changes made it seem imminent. England granted Ireland’s parliament it’s independance in 1782 and the whole country rejoiced that freedom was upon them.

The world of Patrick Dillon was a tough one, full of angry people and escalating violence. Harwood wrote succinctly of the rise of Irish rebellion groups like the Whiteboys and the Defenders.

Most of this was still out in the rural areas. Dublin carried on much as it had before, with just a few brawls and minor riots. Until the French Revolution of 1789 set everything off in Ireland.

Native Ireland and France had a very long connection. France sent aid to assist them in earlier centuries against Protestant England, and right through the 18th century Irish Catholics had quietly slipped out of Ireland to go join the French armies. If an Irish Catholic felt any trust in a nation other than Ireland, it was France. It makes sense that this event would ignite a flame.

The result was war in Ireland.

It took a while to get going. The Irish people banded together, a delegate went to France to ask for assistance which was provided, but bad weather prevented the French fleet from landing. This alerted England to the danger and they sent troops.

A new powerful Irish army was ready. The plan was to take control of Dublin.

It all failed, and it failed very fast. England were clever at keeping Ireland down, and more experienced with the coast and currents than France, plus they were geared up for the Napoleonic wars already and had fresh troops straight across the channel.

The rebellion was crushed in 1798, martial law imposed and even stricter conditions placed on the Irish Catholics. Irish Catholics were rounded up, removed from their land and barred from gathering together. This was the time when hedge schools and surreptitious worship in dense thickets became a thing.

A lot of rural Catholic churches were closed down and the people banned from meeting together.

This is the social climate I wanted to describe here. A world of fear and deep suspicion, great disappointment and anger. A world full of displaced soldiers and rebels who had been stripped of their land.

In the aftermath of the 1798 rebellion, the young Patrick Dillon and Bridget Hayes were optimistic enough to envision a future together. The wedding ceremony was conducted at St. James Catholic Church in Dublin on 24th June 1803.

They settled in the parish of St Catherine’s, in the liberties, an area in the south of the city. Seven children were born to them over the next ten years.

This is all I’ve found so far. They may have moved, or perhaps one of the parents died.

John and James each married a girl surnamed Martin. Thomas married a Murphy. Those marriages took place in Dublin.

My ancestor is Mary and she married in Kildare, forty miles away from the others.

Why would she be so far from home? I still have moments of doubt that these are the same family, but the DNA matches are reasonably strong. They match on the same segments, there’s a paper trail for them all. It’s just a mystery yet to be solved. Maybe the whole family moved to Kildare and only the boys stayed in Dublin, perhaps because they had employment there?

Despite the questions, it’s a very helpful find and I’m sure to learn more as time goes on.