Back to Adventurous Alice Part Three – A Single Young Woman in Western Australia

Back to Alice Head’s Train Journey Part Two – Northam to Southern Cross

Forward to Adventurous Alice Part Four – A Single Young Woman in Kalgoorlie

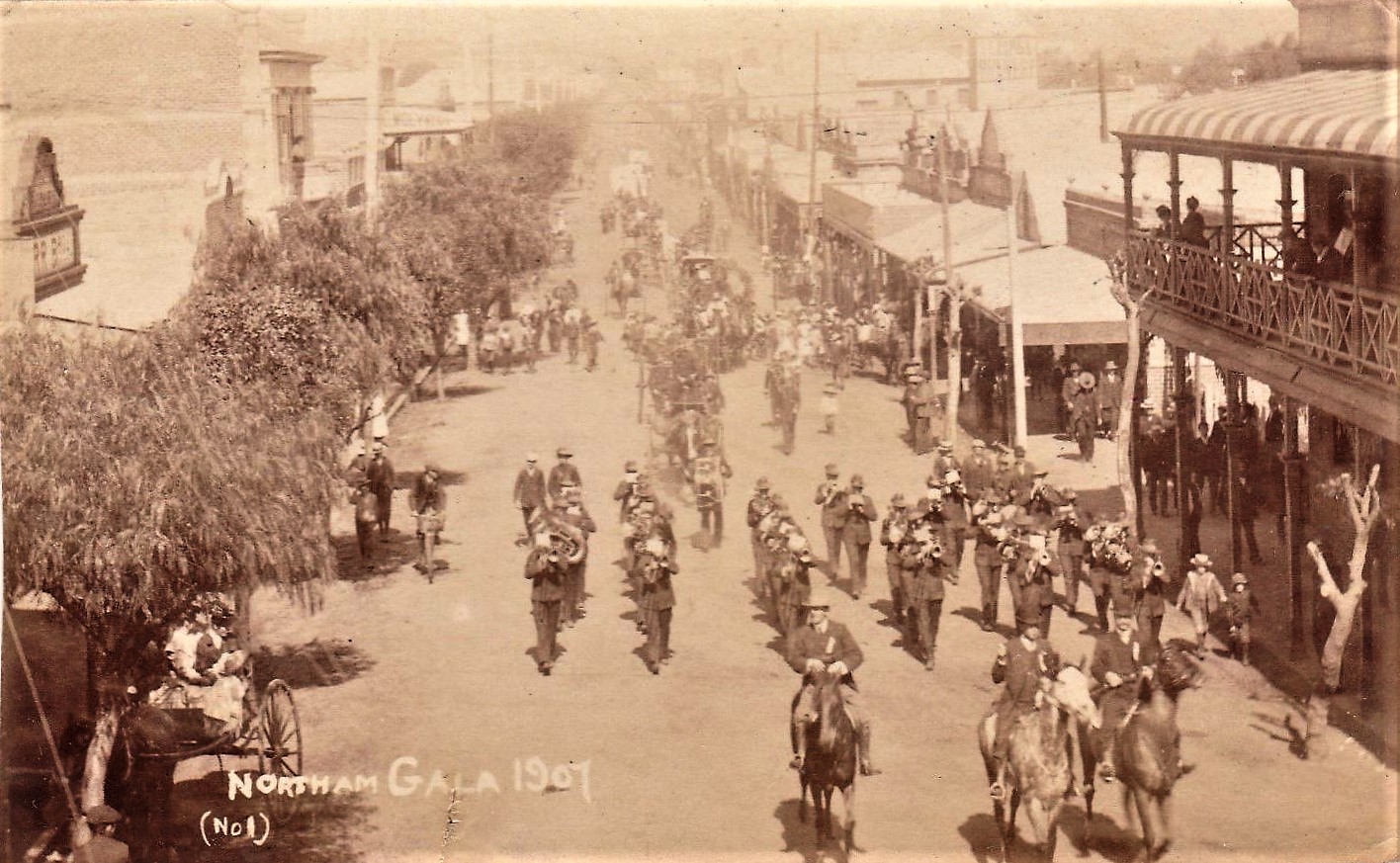

Celebrating the newly opened rail line to Kalgoorlie.

This post concludes the experience of travel by rail from Perth to Kalgoorlie as taken by Florrie and Alice Head in 1897.

Now at Southern Cross station, Florrie and Alice were able to leave the train for a short time to freshen up and eat a meal on solid ground. Even if they had travelled first class and slept on the train, they would be feeling stiff and probably a bit tired. If they had slept in their seats, or if they had started on the early train from Perth and were now at Southern Cross at midnight, they would be feeling quite weary.

From this location in this year, journey descriptions are more obtainable. This first one is from 1896. The ‘terminus’ referred to is that of the Government owned railway – the continuation to Coolgardie was still under control of private contractors Wilkie Bros. :

SOUTHERN CROSSSouthern Cross is a lively place when the trains are in. All the available population is on the platform to meet us … Being now at the present terminus of the Government railways, there is an exodus from the train. The platform is crowded with swags and water bags awaiting the arrival of the contractors’ train. [My friend] who “knows the ropes ” on this route of travel helps me across a barren open space to the Railway Hotel, where a wash and a good breakfast revive me. I got a better meal here than I ever got in Perth, and am very well waited on by attentive hand maidens … The whole talk is of gold. You hear of the mines in the immediate neighborhood – of the “Golden Pig,” of “Frasers”, of ” Hope’s Hill”, of ” Mount Jackson.” … The Alpha and Omega of Southern Cross are gold.At Southern Cross I recognise how little the inhabitants of West Australia have to do with its present development. The people I meet are all from abroad or from the other colonies, New Zealand being specially well represented. (1)

After a refreshment, Florrie and Alice returned to their seats on the train and the journey continued.

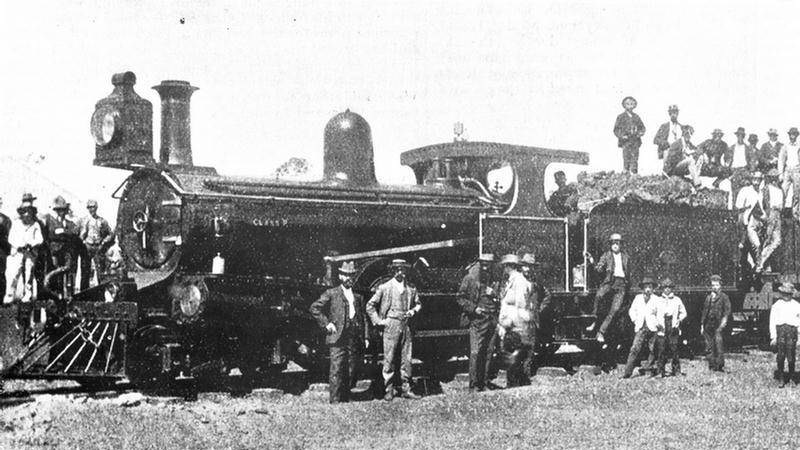

Train at Boorabbin circa 1905. This may have been the very train that Florrie and Alice travelled on, but a few years later.By Passey Collection Of Photographs [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The country traversed by the line is of the usual type of our inland plains ; but it has one characteristic which is happily not general, an entire absence of permanent fresh water. In order to meet the wants of the public travelling on the old coach route five tanks have been constructed between Southern Cross and Coolgardie by the Goldfields Water Supply Branch, and it is only necessary to recall the ‘scares’ which took place when the head of the line reached Boorabbin and Woolgangie, and the special measures which were taken to avert a water famine at the latter place to be certain that, if not an impossible, it would have been a very expensive task to construct the railway had the tanks not been in existence. It is pleasing, therefore, to record that two more large tanks have now been satisfactorily completed at Karalee and Boorabbin. While to more fully equip the line for running purposes with this necessary, at least four more are contemplated, and will, it is hoped, be shortly put in hand.(2)

September 1897: The adjourned inquest on the body of Patrick O’Toole, found dead near the railway, a mile and a half from town on August 31, was resumed to day. Thos Carter, engine-driver of the train to Southern Cross on the night of August 30, said he heard a rattle on the ballast. He reported the occurrence later on to the driver of an incoming train. He did not see anything on the track. Thos Stephenson, driver, stated that while driving a train from Southern Cross to Coo!gardie on 31st he saw a man on the side of the track. He did not stop, but reported the matter at Coolgardie. Dr McNeil, medial officer … held a post mortem examination … The injuries could be caused by a train. Neil Douglas, District Superintendent of Railways, said the first duty of the engine-driver was to see to the safety of the passengers. There were no specific duties laid down for him when he saw a body beside the rails. There was nothing in the regulations to prevent him pulling up. The jury returned a verdict that the deceased came to his death by being knocked down by a train. They recommended that the departmental instructions to be given to the engine-drivers when seeing a body near the line should be more clearly defined (3)

Coolgardie in 1906. Public Domain.

BOORABBIN, January 3 1897It is reported this morning that a man named O’Dea, said to he suffering from delirium tremens, has been lost from the ballast pit, two miles west of Boorabbin, since Friday last. He has been traced to a mile from the tanks, where the recent storm and rain have obliterated his tracks. The police are now doing their best to obtain a black tracker from Coolgardie or Southern Cross. (4)

Coolgardie August 1898: A miner wandered into the bush on Saturday night. As he was missing on Sunday morning, a large search party went out. He was found in the afternoon much exhausted, having got as far as the Thirty-Five Mile. A noble feature in the Australian character is that of brotherly help in cases of distress, a feature that will greatly aid the efforts that are being made to build up a great nation. No country can be great and prosperous unless its people are plucky and enterprising, and willing to sacrifice individual interest and comfort for the common weal.(5)

March 1896: Leaving Southern Cross at 12:30 on Monday morning very slow progress was made on the contractors’ line. In consequence of the reported approach of a down train a halt of about three hours was made at a spot fifteen miles from Southern Cross. A fresh start was effected at seven o’clock, and short stays wore made at Boorabbin and Bullabulling en route. At 11.30 the travellers were glad to find that their destination, Coolgardie, was in sight. (6)

Coolgardie. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coolgardie.jpg By Richard Riley from Nottingham, England (Coolgardie) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The proximity of the golden city of Coolgardie was soon known after the train had restarted, by the familiar condensing plants and adjacent hessian huts. Then we ran through what appeared to be a goods shed, which was observed in the open and thousands of tons of all descriptions of produce and machinery lying on both sides of the line, waiting to be taken on. A few minutes afterwards the train pulled up at the Coolgardie platform, where there was an enormous crowd waiting, despite the fact that it was barely half-past seven in the morning. There was little or no demonstration of any kind, and the guests quickly disembarked. Some were driven while others walked to the various hotels for breakfast. It was an ideal spring morning, the bright sunshine and cool bracing breeze making things very pleasant, and in no circumstances could strangers have seen Coolgardie to better advantage. (7)

Coolgardie had been the end of the railway until September 1896 and was still a big and bustling town. Florrie and Alice probably saw little of it, except the part they could see from the train windows. The train stopped here for at least half an hour. It was a watering stop and a lot of freight was also loaded and unloaded.

Camel Team at Coolgardie 1900 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Camel_team_Coolgardie.jpg

A passenger complained to one of the papers about overcrowding in the trains, stating that while hundreds of passengers disembarked at Coolgardie, hundreds more boarded for Kalgoorlie. Other reports confirm this.

February 1897: The traffic between the coast and Coolgardie shows no diminution. Passengers are arriving in hundreds, daily, and merchandise in thousands of tons. (8)

Nov 1899: The District Traffic Superintendent of Railways, Mr Douglas, – yesterday visited Coolgardie to interview a deputation representing the citizens to deal with the unsatisfactoriness of the train service between Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie, and vice versa.… Their principal grievance was that trains were not ran to the time-table, and in consequence their business was interfered with, and that there was a considerable difference between the times of the clocks at each station, by which any traveller was liable to miss a train. They also asked that the stoppage under the. bridge should be done away with, and ‘that a shunting engine should be permanently stationed in the Coolgardie yard. They enumerated several instances of the late starting and arrival of trains …

Mr Douglas’ response:The traffic between Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie was now very heavy, and warranted the line being duplicated. In reference to the difference in the clocks, he said that at 1 o’clock each day the’ telegraph operator at Kalgoorlie received the correct time and forwarded it to every station on the line between there and Southern Cross. The clocks were then adjusted, but there was no excuse for anyone opening the clocks except at that hour. (9)

Perth to Kalgoorlie. Circa 700km.

It wasn’t all that far from Coolgardie to Kalgoorlie, considering the length of the total journey.

Shortly after nine o’clock, the last stage of the journey was entered upon. … the country en route is quite as uninteresting as the other portions are, from a scenic point of view. As the line had not been ballasted, ‘slow ahead’ was the rule, and a journey of about two hours brought Kalgoorlie into view. (7) – continued from earlier description

Here’s a humorous but elucidating description of the journey between Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie:

July 1897: THE most captious critic of the railway system of this province cannot complain that the drivers of locomotives rush at breakneck speed, regardless of consequences and the cost of coal, over the long, straight, level streaks of track. At the same time the assertion of a boastful citizen, that he would back his grandfather, aged 78 on the 16th of last August, to walk to Kalgoorlie in less time than the train takes to make the journey, must be regarded as an exaggeration. No man of that age could do it. The distance would beat him. and the pace would run him pretty close. The distance is twenty-four miles, which, with everything right and the line clear and the wind dead astern, is sometimes negotiated in two hours, and sometimes in more.The train is scheduled to leave Kalgoorlie at 6.30 p.m. and arrive at Coolgardie at 8 p.m. Sometimes it does, more times it doesn’t, and the consequence is the reviling of the Department and the responsible officials. Many citizens of this centre whom business attracts to Kalgoorlie several times a week venture to make appointments for the evening in Coolgardie, but they propose and the authorities dispose. The train is rarely on time. Often it is very much behind time, and appointments involving large interests or engagements on which important ventures may depend are perforce broken to the mutual annoyance of the parties. …We think … the line could be cleared and the stops at many of the by-stations done away with, as at present the engine is halted for no apparent reason at places the population of which is chiefly a wall-eyed man washing a tea-cup and a frantic woman who appears desirous of striking someone on the train with a bottle of beer. Life is too short to crowd much of this kind of entertainment into it. What we want is to do our business and get quickly from place to place in pursuit of the same.… On the first day of next month a new time-table is to be instituted, and under it we hope to see a train timed to leave this town at say 8 o’clock in the morning and arrive at Kalgoorlie at the end of one hour. A second one should run in the evening, in addition to the ordinary mail from Perth, and from Kalgoorlie a similar number should be provided. If this is done, a great boom will be given to the people of both centres, and after all the public own the lines, and public convenience should be sometimes studied.(10)

The Nullarbor. Indian Pacific Railway. Kalgoorlie – Adelaide. WA – SA. Loongana WA. Amanda Slater via Flickr. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/ . No changes made.

So at this point, Florrie and Alice’s train will have steamed into Kalgoorlie where a scene of great activity ensued while all passengers collected their belongings and disembarked. We don’t know if they had arranged accommodation in advance or if they sought out somewhere to stay upon their arrival. Possibly, it was a large group including Florrie and Alice, Jessie Gray, Jean Christison, Henry and Elizabeth Wilkinson, and Margaret Brown.

(1) “SOUTHERN CROSS.” Leader (Melbourne, Vic. : 1862 – 1918) 30 May 1896: 6 (“THE LEADER” SUPPLEMENT). Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article196655424>.

(2) “Extension of the Railways.” Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1950) 2 January 1897: 2. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article87853458>.

(3) “COOLGARDIE.” Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916) 9 September 1897: 24. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32428682>.

(4) “BOORABBIN.” Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954) 8 January 1897: 15. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33140026>.

(5) “SOUTHERN CROSS.” The W.A. Record (Perth, WA : 1888 – 1922) 6 August 1898: 14. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211842123>.

(6) “OPENING OF THE COOLGARDIE RAILWAY.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 24 March 1896: 3. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3084232>.

(7) “THE KALGOORLIE RAILWAY.” The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950) 8 September 1896: 3. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article84467008>.

(8) “COOLGARDIE.” Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1869 – 1912) 16 February 1897: 3 (ONE O’CLOCK EDITION). Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207889635>.

(9)”KALGOORLIE RAILWAY WANTS.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 7 September 1899: 6. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3234447>

(10) “Wanted—Steam.” Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1894 – 1911) 14 June 1897: 4. Web. 29 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article216698206>.