There are many ways to approach the research of any ancestor, and one useful deciding factor is their level of education. A man who could read and write well probably signed his own documents and had an idea of how his surname was spelled. One who couldn’t had to rely on the ability of the official recorder.

William Truitt, for instance, born in Yorkshire in 1708, could not read or write. His children were baptised under the surname Triffitt and William died a Triffitt too. His Yorkshire accent was interpreted as best the minister could.

The three Dillane brothers convicted in Ireland arrived in Australia as the three Dillon brothers. John Reddan became John Reading. Burlington became Burliton then Burleton. Anyone researching family history becomes familiar with the evolution of names. Points of emigration were a particularly problematic time.

It also fills out a family story nicely to work out what education someone had. It’s one of my ‘prod’ questions, the ones I use when an ancestor ceases to be a real person to me and becomes a bunch of facts. Sometimes I will located baptism, marriage, death and occupation and feel as if research is done on that ancestor but I don’t really know anything about them. This is bound to be the family on which I trip up.

Education has been around for as long as records and of course this is no coincidence. It was only when humankind learned to pass on its knowledge that any sense of difference could have been recognized, across the generations. There are children, there are adults, there are old people. Old people die, children are born. Once that must have been the extent of it with a whole lot of reinventing the wheel going on.

For the next few thousand years children were educated in the things it was believed they would need to survive. This remains the rationale today. In some societies what they became as adults depended on what they happened to have learned. In others, what they were from birth determined what they would be taught. In most societies the situation fluctuated century by century or decade by decade.

England had a very exciting educational revolution in the early 19th century. Until the 18th century they operated under a stable system of rich families educating their sons to be thinkers and leaders and their daughters to be examples of propriety and health to the masses. The masses were taught the labouring skills they would require and the morality to stay diligent and not become a burden on society. The system worked well for a long time, it would seem, until the second half of the 18th century when new knowledge led to a dramatic increase in population. Infant mortality declined greatly. Once a farming family birthed ten children and lost six. Now they lost maybe one or two.

A system that worked on the village level no longer functioned. England had allocated a fixed quantity of resources to its masses and when the population exploded they were not prepared to give more to them. Crown land was passed over but the aristocrats were not so altruistic. Not only that – they suddenly had more of their own children growing up too.

In their defense, this issue was not easy to see. We can do it in hindsight, but without walking a day in the shoes of the peasantry, a noble family could not perceive the problems of inadequate diet, the need for greater sanitation, the inability to clothe ten children on an income which once adequately clothed four.

What they did see was more crime and idleness. The initial response was to tighten the laws, to make the punishments stricter. Theories abounded as to the cause, but not many hit on the true ones. The most common theory was that they were born somehow twisted – morally twisted. The churches were put to work on them but if the church couldn’t save them, they were executed.

One thing the church tried in order to bring the peasantry back under control was basic education. They were taught to read so they could read their bible.

There were a colossal number of executions in earlier centuries and reading through the newspapers of the 18th century one sees huge lists. It’s quite tragic – names and ages. Most of them seem to have been teenage boys from the farms – surplus workers whose own families even did not realize how hard it was to get work. They probably felt inadequate. They certainly felt aimless and fell into unfortunate lifestyles. Then life was cut off before many of them reached adulthood.

The tide was turning against execution though. More and more petitions were being got up to bring it to a halt. Local Members brought the matter to parliament, as raised by their voters. It was just too much death in a society being taught to forgive their enemy. State-controlled transportation was the result. Transportation was a well established practice but now it became a properly organised process.

We all know that education became state-controlled in order to provide a work force for the industrial revolution. To me, this is a somewhat simple overview. Literacy was encouraged to aid the churches in teaching Christian values and moral behaviour. Schools became a way to keep the idle occupied and to train the poorest students into a profession whereby they would not be a burden on the community. For many centuries, wealthy men would bequeath funds to the local charity school to assist in this important task. The successful management of the poor led to better success for a town. A community could be well and truly dragged under by too many incapable beggars.

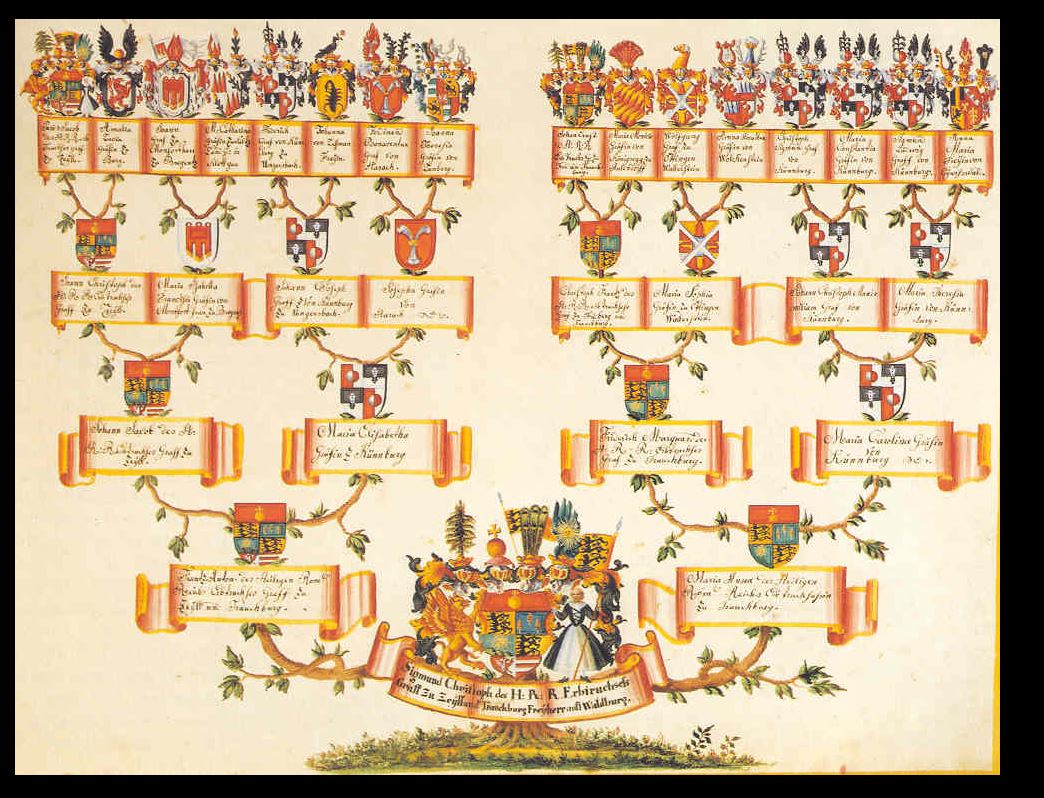

The wealthy continued to spend a lot of money educating their young. Governesses and tutors were brought into the home or the boys went to boarding schools, private or public. As the 18th century drew to a close it was becoming more common for girls to attend boarding school also, just for a couple of years. These were not boarding schools as the boys experienced, with hundreds of students per class. The girls were in little cottage schools with a total enrolment usually of ten or under, run by an educated lady of good birth with her own genteel residence. It was a good position for a lady with a house but no accompanying income.

Small boys’ schools were started in the same way, by a school master without a position in his own house who would take just a few private pupils. It wasn’t so different to an apprenticeship, probably, except the master received fees and the students learned Latin, mathematics and geography instead of a trade.

The introduction of the Poor Law in 1834 had an impact on orphanages and turned them into Schools for Orphans. These orphan and pauper children were the original targets of the school system which trained for industrial positions. Workhouses also taught basic literacy and numeracy. However, the honest working poor then discovered that pauper children were better able to enter employment than their own young ones. It caused an upheaval and a paradigm shift which is fascinating to examine through the records.

Having set the scene for education in the United Kingdom, I can take a closer look at the educational experience of some of my ancestors.