The 18th century in Limerick is truly fascinating to study. After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Cromwell came in with the New Model Army and did his thing. Fifty years of fighting ensued, culminating in the Limerick Siege of 1691. After this, Irish Catholic Ireland returned to British Protestant control and matters sort of quietened, at least as far as England was concerned. The decades passed with rebellion flaring up in small pockets across Ireland constantly, like the aftermath of a forest fire that is still too hot to completely die out.

This was the world of my 6x great grandmother Dorothea, who lived till her 95th year.

I chose Dorothea because she lived at a time when women did not commonly reach her years, especially not a woman who raised a family as large as hers. She qualifies in the theme of ‘longevity’ as one of the longest living of my ancestors. I should warn you all – this post probably qualifies also on the grounds of its own length. There was a lot to put in.

It is easy to be satisfied with the dry basic record one gets through peerage records and military notices, but as I sat down to write this post, I was determined to get beyond this. Those ancestors of mine were real people who lived full lives that I would love to know about. Dorothea was born in Limerick and died in Cork, but she experienced a lot between those two events.

So I asked myself, what was life really like for Dorothea?

SARSFIELD BRIDGE AREA OF LIMERICK by William Murphy, taken 09 Jun 2014, no alterations. Used here under Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

She grew up in a place justifiably proud of its role in the war against Protestant Britain. The greatest resistance to British rule came from the city of Limerick, which was attacked and besieged again and again between 1641 and 1691. The fortified garrison was an inspiration and a symbol of strength to the Irish armies. Even Thomas Leland, a man firmly set against the “Romish” barbarians, refers to Limerick in his ‘History of Ireland’ (1814), as ‘the great and final refuge of the Irish’ (1).

The citizens of Limerick city knew just how to survive a siege. In 1691 they settled themselves in as so often before, repelled attacks, patrolled and repaired heroically and masterfully. They nearly won the war, too, but starvation and disease broke them just a few days too soon. They came to terms with the aggressors shortly before a French army arrived with new resources for the Irish resistance. The entire history of Ireland could have been quite different had they lasted another week. As it was, the 1691 Treaty of Limerick became the guiding document for the Irish people.

This event and its aftermath were defining features in the lives of everyone who lived in Limerick county in the following decades. The treaty itself was memorialized in stone and set into main square of the city.

‘Limerick City – Treaty Stone’ by William Murphy accessed via Flickr. No alterations. Used under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0. See conditions of use here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

After the treaty, a lot of influential men of Ireland were attainted and removed from their positions. Reparations were nothing to do with religion but entirely based on which monarch each person had allied themselves with. Irish troops were given the option of emigrating permanently to France. The historian Maurice Lenihan (1866) states that about 21,000 soldiers took up the offer and left Ireland without their wives and children (2). His history includes poems and songs of woe, apparently composed at this time.

Very heavy restraints against Catholics were introduced too. They were basically under curfew, not allowed to leave their district or entertain guests. The restrictions were deemed a betrayal perpetrated against the Irish, definitely not a condition referenced in the Treaty of Limerick. Daily life resumed, but tension was constant.

All of that occurred fifty years before Dorothea was born, but by 1744, Limerick was still trying to recover.

Dorothea’s family were Protestants, so she was not impacted by the Catholic restrictions. But she was still born into a climate of suspicion and danger. Most likely she was never allowed to wander alone. The servants were probably what was known as retainers – multi-generational family servants on unofficial tenure. There was no knowing when war would erupt again, when a new administration would look over the business and private activities of every family to seek out ‘traitors’. It mattered very much whom one associated with, whom one was seen with, who was seen coming to one’s door. Dorothea undoubtedly led a heavily sequestered childhood, only associating with trusted family and friends, only playing with the children who it was safe for her to know.

The obvious result here is a lot of intermarriage within a small social circle. This part of my family tree is more like a family spiderweb with tendrils flying everywhere, hooking on to other strands in complex and confusing ways. The strands never came too close for comfort, but there is a noticeable amount of pedigree collapse. Dorothea is right in the middle of that.

‘Portrait of a Young Girl’ by William Hogarth. Public Domain image of a girl of about the same generation as Dorothea. Maybe – perhaps – she looked something like this?

The Hunt family had lived in the county of Limerick for a hundred years by the time of Dorothea’s birth. Her great grandfather was Vere Hunt, an officer in Cromwell’s army who received extensive lands around the garrison city of Limerick in the 1640s (3). His son Henry, her grandfather, married Aphra Aylmer of Croagh in Limerick, a land-owning family who had been there apparently long before Cromwell’s arrival. In later years, the Aylmers declared a strong tradition of support for Irish independence, but they seem to have avoided any penalty after the Limerick siege.

Thus the children of Henry and Aphra, including Dorothea’s father Henry, were quite wealthy and well-connected. Henry Hunt the younger was a privileged young man of good prospects when he married Margaret Widenham in 1730. It was on the occasion of his marriage that he bought the large house and property at Friarstown, where Dorothea was born in 1744.

I don’t actually know how many children there were in Dorothea’s family. The peerage books all mention Vere, the eldest. The GUI Landed Estate Index (3) says that his third son Henry lived at Clorane in Ireland. So we have Vere, an unidentified second son, Henry – and somewhere later on comes Dorothea. There were probably a lot more.

‘Entrance Curragh Chase Forest Park’ . Limerick outside of the city was a very rural place in Dorothea’s time. Image by Peter Gerken [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Dorothea’s position in society was the same as that of the lower aristocracy in England. She was well-born, well-connected, her family had a tradition of local rule and hereditary manors and they had money. But in other ways, her life was quite different. She had a knowledge of cruelty and danger that her British counterpart lacked – no matter how sheltered her life was, this could not have been avoided. The atrocities of the 1641 Rebellion were barely out of living memory, the sieges had been experienced by people she knew, and the city of Limerick still bore many scars of battle in its buildings and walls that she would have seen any time she visited the city.

Most likely there were fewer governesses of quality to teach her to dance, to play the piano and to speak French like a princess. There were no hunting parties, no London season, no Hyde Park to go to in a carriage. She daily witnessed the regiments stationed permanently on guard at all public areas of Limerick city, keeping the peace in a way that was not required in England. There were very few bridges, very few roads.

She probably had lots of things though – Limerick’s shipping port was very active with trade. There might have been silks and jewellery and books, writing compendiums and lip paint, if her parents approved. She may have had a doll’s house, she may have had a hobby horse. But childhood was short in 1750 when children were thought to be mini-adults, children in a physical sense only.

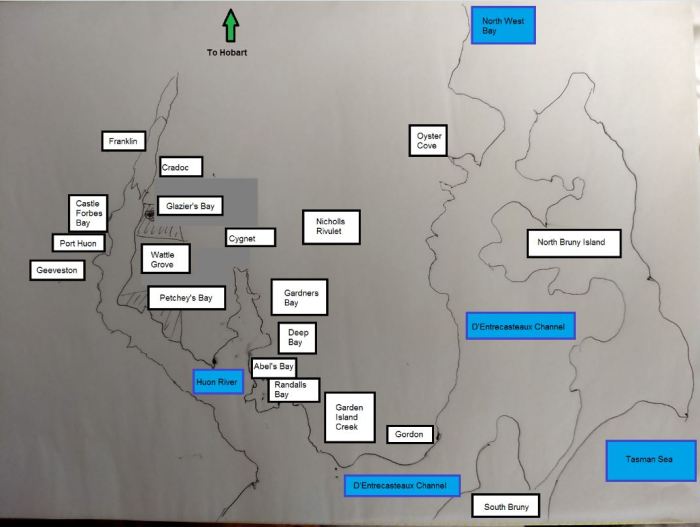

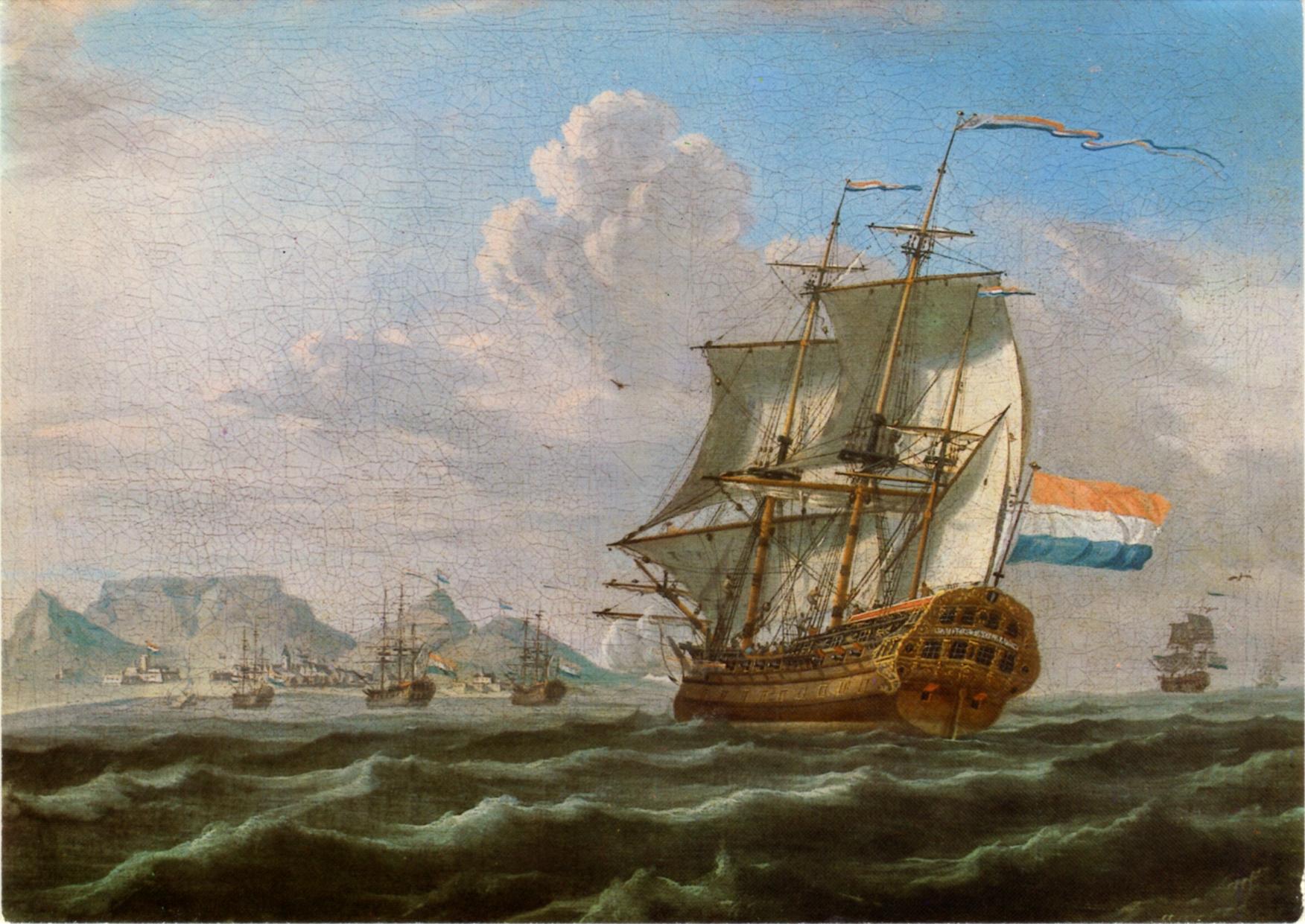

1762 ship, the type of ship which Dorothea may have seen in Limerick. By Anonymous (18th century) (Postcard) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In a family of civic importance, the public duties may have started early. It was common for the daughter of a prominent townsperson to pass medals to soldiers in military ceremonies, to present business awards while standing beside the town mayor, and at other times to sit quietly – with an expression of interest and respect through interminable speeches by businessmen who loved an opportunity to demonstrate their oratory skills.

The Irish class system was also different to England’s. The Irish aristocracy lived more familiarly with their clans, not seeing themselves as unreachably superior. There was class mobility. Ireland in that century operated more on a patronage system, something England was trying hard to stamp out. Positions of importance in Ireland were available to any man with the right skills who was verified by someone of suitable authority. If that person met with trouble, their patron and his friends would come instantly to their aid. It seems that if the person failed in their trust, the one who had vouched for them was obligated to take the blame and repair the damage, so the whole business was taken very seriously. The entrenchment of societies such as Freemasons was a natural progression, as were the banditry fraternities such as the White Boys and the Rockites.

To be a Protestant in the 18th century in Ireland was almost a guarantee of a comfortable life, financially speaking. To be landed gentry gave even more privileges. It would have been hard for a landed Protestant not to succeed in all ways; financially, in his career and in his land acquisitions. England desperately needed the Protestants to stay, to take charge so that the Catholics could not gain dominance. After the wars, many English landowners had moved on. They went back to England, to Barbados or to Virginia where it was safer. England threw a lot of incentives and resources at those who stayed.

The British Protestant settler in Ireland braved the emotionally charged threat of the disenfranchised Irish. They weathered the deprivations of war-ravaged agriculture and the absence of infrastucture. The benefits might be great, but the risk was that a raging mob might charge into your house and slash everyone’s throats at any time, or one might be shot dead by snipers on the way into town. It did happen. This was a scenario that no genteel English young lady had to face.

18th century cannon and soldiers, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=156768

John Ferrars’ history of Limerick adds colour to the years of Dorothea’s childhood. His history was based on the manuscripts of the Reverend James White, a long time favourite of mine. I’ve read John Ferrars’ book many times now.

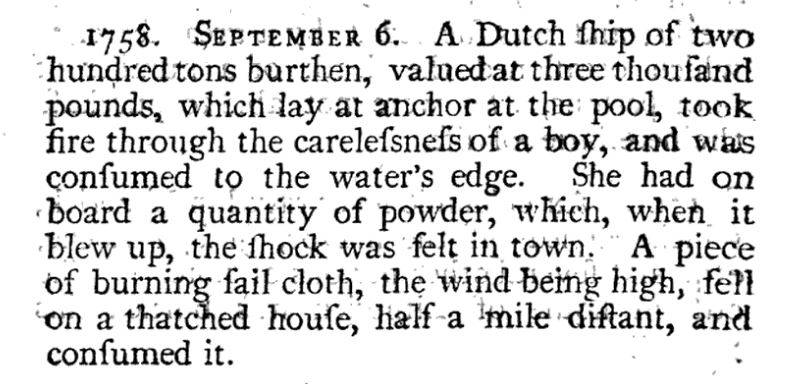

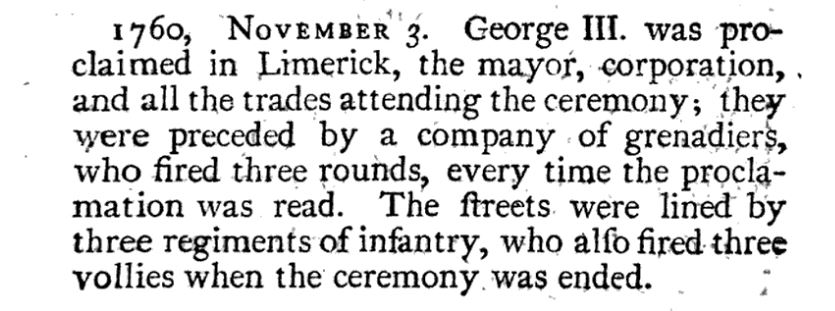

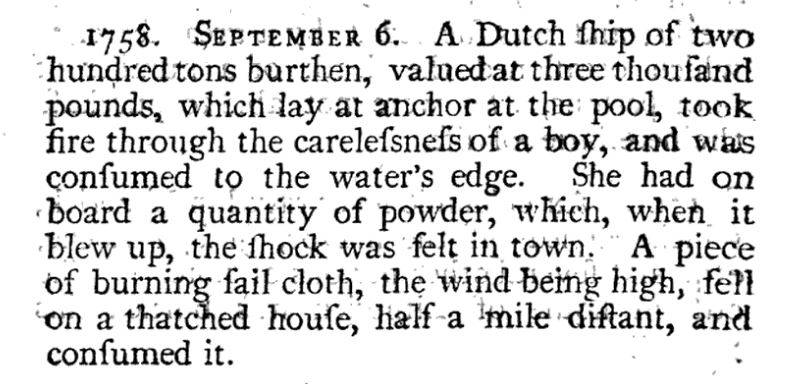

History of Limerick by John Ferrars 1767, page 128 (4)

Dorothea was fourteen at the time the ship blew up.

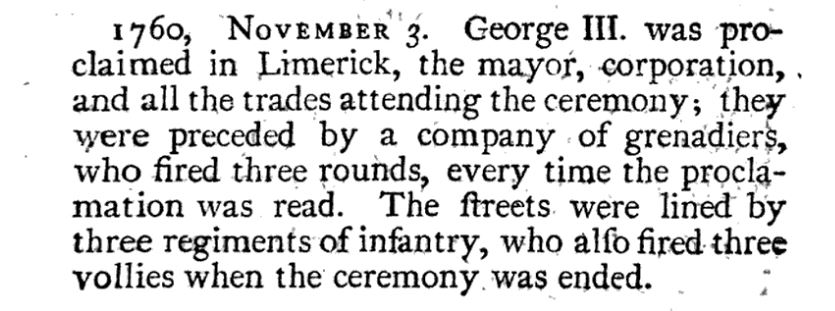

From John Ferrars’ history of Limerick 1767 p 129 (4)

Dorothea was sixteen years old and probably attended, since her parents were important members of local society.

In 1762 when Dorothea was eighteen, the White Boys first appeared in Limerick, perhaps an indication that many people were experiencing tough times. The White Boys were a society of rebels/bandits who attacked the Protestants and those who worked with them, in revenge for atrocities committed against the Irish Catholic. Some of their acts were very vicious.

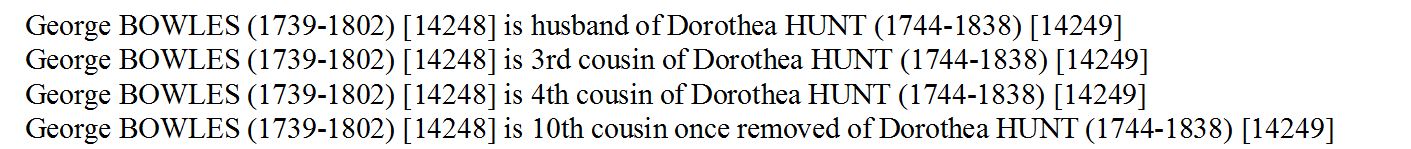

When she was aged nineteen, Dorothea married twenty-four year old George Bowles (Boles), a cornet in the 7th Light Dragoons who was stationed at Limerick at the time. He was a distant relative of hers.

In fact:

Relationship between George and Dorothea in my family tree

The relationship finder actually found fifteen different ways in which George and Dorothea connect, but these are the closest. Dorothea’s great grandfather Thomas Maunsell was the brother of George’s great grandmother Aphra Maunsell. The relationship was barely worth noting, but it meant that George was safe for Dorothea to know, and that it was safe for the two families to be united.

Grenadier, 40th Regiment of Foot, 1767 . An example of a soldier of almost the exact year that Dorothea met her husband. Each regiment had their own uniform and this is not the correct regiment, but the basic style was the same. By Inscribed “PWR” [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

George was a son of the respected Boles family. According to Burke’s Peerage, the spelling of his name was entered erroneously on his commission papers and he decided it was simpler to keep it. It is also possible – subtly implied by Burke, I think – that he chose the more English spelling deliberately but allowed the story to proliferate to save his family’s pride. After all, some of the Boles family had lost their privileges by taking the wrong side in 1691. It might have been prudent to

not remind his senior military officers of the connection, in any way. I’m just speculating here.

They married in Limerick on 13 November 1764 and moved to the Bowles family property of Mount-Prospect in Curriglass, Cork. This is where their children were born.

Burke’s Peerage and the GUI Landed Estates both state that George and Dorothea had three sons. This is true. They also had nine daughters, something which is rarely mentioned. This was actually a large family.

Children of George and Dorothea Bowles of Mountprospect

There is a gap in children between Henry and Anna which I can’t yet explain. I do know, however, that George Bowles purchased a commission as Lieutenant in 1767 (6). It was announced in Military Notices as follows:

War Office Feb 14, 7th Regiment of Dragoons, Cornet George Bowles to be Lieutenant, vice Lieut. Samuel Bayley, by purchase.

He then exchanged from full pay to half in 1769 (7).

George was appointed a Justice of the Peace in Curriglass sometime before 1770. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Tallow in 1776. Curriglass and Tallow are geographically very close to each other.

In the 1790s when Dorothea was aged about forty eight, the family travelled to India where George was referred to as ‘General George Bowles’ (8). While in Bombay, India in 1792, Dorothea’s daughter Dorothea was married to Major Henry Oakes. It seems that the whole family were there at that time.

Perhaps he really was a General, but there is usually enough documentation regarding military Generals to confirm it. I’m not convinced, I suspect someone was making an advantageous marriage sound even grander.

I haven’t found another mention of George Bowles anywhere. Although many sites say that he died at Tallow, I am beginning to think he actually died in India. This is based on his daughter Harriet’s marriage in Bombay in the year of George’s death. Why would the family still be there if he wasn’t?

George died in 1802 – supposedly in Tallow, Waterford – leaving Dorothea as executrix of his will. Dorothea returned on a date unknown to Mount-Prospect, where she lived comfortably surrounded by extended family including her Widenham cousins.

In 1830 when Dorothea was 86, the property was advertised to let (9). I don’t know where Dorothea lived during this interval . The house being new is a surprise also. After George’s death, the property was inherited by Dorothea’s son George, but given to Dorothea for her use through her lifetime. Maybe George the younger or his wife were not willing to live in an outdated place? Or maybe they did preferred to live in their own way, separate to Dorothea.

The ‘Mrs G Bowles’ referenced in the advertisement could have been either Dorothea or her daughter-in-law.

DESIRABLE RESIDENCE

TO BE LET FOR A SHORT TERM

The HOUSE And DEMESNE of MOUNT-PROSPECT, with OUT-HOUSES and an excellent GARDEN, near the village of CURRIGLASS. The House is a new one, and fit for the reception of a large family.

Applications to be made, if by letter (post-paid) to Mrs G. Bowles, Mount-Prospect, Tallow.

About the only other reference I have found to Dorothea in her own right is a court appearance she was required to make in 1833 regarding the particulars of a lease of land which had been allocated in her husband’s will thirty years earlier. She was aged 89 and probably did not actually appear in person.

Dorothea passed away in Ahern, Rathcormack, Cork in 1838. Unfortunately despite all the searching I have not located her actual death date, simply the probate record which gives the year and location of her death.

Thus ended the life of a woman who saw a lot in her time, who birthed twelve children, travelled to India and spent thirty years in widowhood managing her own affairs. Even this long blog post just skims the surface of her life, but it is a closer and hopefully an illuminating look at someone who is entered in all the peerage records only as ‘Dorothea, daughter of Henry Hunt of Friarstown, county Limerick’.

(1) The History of Ireland from the Invasion of Henry II by Thomas Leland, 1812 via Google books https://books.google.com.au/books?id=UAVaAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA364&dq=history+of+limerick&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjKnd6O3tjYAhWGybwKHQKKBTw4KBDoAQhRMAg#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20limerick&f=false

(2) Limerick: its history and antiquities by Maurice Lenihan, 1866 via Google books https://books.google.com.au/books?id=YwwHAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA1&dq=history+of+limerick&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjFttDB3djYAhUGbrwKHQfKBZ0Q6AEINDAC#v=onepage&q=jonathan%20&f=false

(3) http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/estate-show.jsp?id=2636

(4) The History of Limerick, Ecclesiastical, Civil and Military by John Ferrars, public domain via https://books.google.com.au/books?id=0YY2AAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=history+of+limerick&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjFttDB3djYAhUGbrwKHQfKBZ0Q6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=friarstown&f=false

(5) Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 26 February 1829 – Advertisements

(6) Leeds Intelligencer 24 February 1767 – Notices via FindMyPast.com.au

(7) The Scots Magazine Military Notices 1769

(8) Biography of Major Henry Oakes https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive/under/research/biographies/oakes.html

(9) Cork Constitution 24 August 1830 Notices via FindMyPast.com.au