The first concrete evidence of George Richards is his marriage in 1828 to Ellen Cummings. He comes through records as little more than the husband of the more visible Ellen and as the father of a bunch of children. Recent DNA matches have confirmed my ancestral line back to George and Ellen, so maybe he is about to appear clearly to us at last.

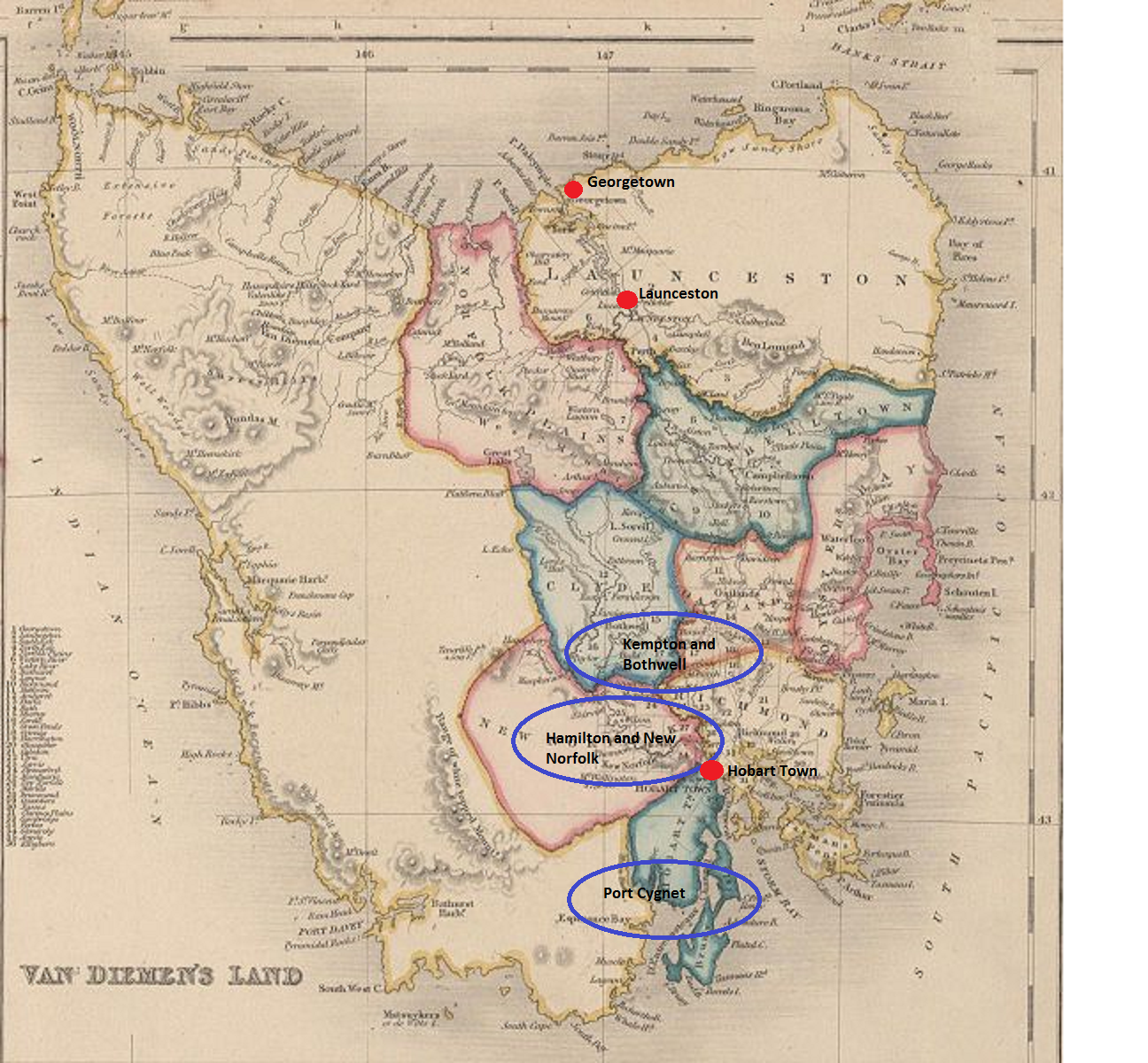

Those who read my blog will have become familiar with a few regions of Tasmania by now, particularly the districts around the townships of Hamilton, Kempton and Port Cygnet. George Richards lived further north, in Launceston.

For geographical context:, here is Van Diemen’s Land 1852 with the regions marked which have been referenced in my blog:

Map from Wikimedia Commons

Map from Wikimedia Commons

In the beginning of white settlement, each region was its own discrete world. People certainly travelled between regions, trade was conducted between regions and they were all administered by the same Colonial administration. But the local flavour in each area was very strong, heavily influenced by those who lived there.

So far, this blog has focused on the south of the colony. But there was a north too, with different settlers, different discrete regions and very different flavours. The north of Tasmania has its own unique history. So now to bring all readers up to speed in a few short paragraphs!

Right from the beginning of British control of Van Diemen’s Land there was debate over where administrative government should be placed. It was briefly in Risdon Cove (now a suburb of the present day city of Hobart), then transferred north to Port Dalrymple (later Georgetown), then to Launceston and then back to Hobart Town where it then remained. All of these shifts were in that first decade of settlement. Risdon Cove was settled by Britain in 1803, Port Dalrymple and Sullivan’s Cove (Hobart Town) in 1804 and lastly Patersonia (Launceston) in 1805. These initial settlements were basically a few shiploads each of handy colonists, soldiers and some cattle. They came off the boat into heavy forest, cold weather, much rain and mud. Over the next three years, building work began, streets were laid down and jetties were built. We’ll now focus on the two northern settlements of Georgetown and Launceston which had received these names by 1810.

I don’t want this post to be a heavy read but a few elements of the epic tale of early settlement are relevant.

The neighbouring colony of New South Wales began in 1788 and by the start of the 19th century it was a proper little settlement. The administrations of the two colonies had a brotherly relationship and were each governed by England, but each colony was required to achieve self sufficiency on its own.

Here’s a map showing Sydney (in the colony of New South Wales) and Port Dalrymple (in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land).

Location of Rum Rebellion of New South Wales and of the Van Diemen’s Land settlement of Port Dalrymple (Footnote 1)

In 1808, a famous military coup was staged in New South Wales by soldiers who felt the place was being dangerously mismanaged. This mismanagement stemmed in part from a circumstance where coinage had not been established and was rare in the colony. With no way to buy or sell using coins and no way to pay soldiers their wages, rum became the accepted substitute. Soldiers were in a perfect position to receive new shipments of rum which they could purchase at good prices and then sell on with a profit. Price gouging, alcoholism and an unhelpful balance of power ensued. A newly appointed colonial governor was given orders to correct the situation. The result was outright rebellion. This event is known in history as the Rum Rebellion.

The rebellion took a while to quell but once this was achieved, the problem of what to do with the offending soldiers needed to be resolved. England didn’t want them back but they were now a properly networked and coherent group who might rebel again. The soldiers were court martialed en masse, but these guys had all lived together in a small community for years and they were deemed to have acted with good intention. It was decided to separate them to a multitude of small new settlements.

Some were offered land grants in the new settlement of Port Dalrymple if they resigned of their own volition. It was an acceptable arrangement for all involved. By 1812, ex-soldiers and their families were trickling south to take possession of their new land. Thus in about 1812 came the family of toddler Mary Ann Elinor Cummings – known as Ellen – whose father had been an officer in the Rum Corps. The dramatic tale of the Cummings family is worthy of its own blog article. All that is relevant here is that the young Ellen arrived sometime between 1812 and 1816.

I tried to find a photograph of Launceston but on my last trip through it looked like this. However, this is probably a good indicator of life in the region on a winter’s day. This was taken circa 11.00 am around 20km south of the city of Launceston.

So, back to Launceston. Descriptions occasionally appeared in local papers.

1812:On arriving at the rising ground above the Town of Launceston, it is impossible to avoid being struck with the beauties of the situation, which commands an extensive view of the River Tamar, as also of the Rivers North and South Esk, winding through a country, at this particular place of wonderful fertility. But the extreme difficulty of the navigation of the River Tamar, and the great inconvenience which the inhabitants experience from the want of fresh water, with which they are supplied from the Cataract River only, by boats, owing to the tide flowing up the Rivers beyond the Settlement: this circumstance, combined with the low and damp situation of the Town, (which is situated at the confluence of these three Rivers), has induced the Governor to determine on removing the chief Settlement of Port Dalrymple to a situation which can afford His Majesty’s ships, and trading vessels, a ready and easy place of refreshment on their passage through Bass’s Straits – an object quite out of the reach of shipping where the Settlement now is. (Footnote 2)

In this decade, Launceston had no newspaper of its own and is generally referenced in other papers as a shipping destination, but a few articles give a clue about life there.

1817:

It appears about the 25th ult. that … bushrangers committed a robbery near Launceston – that the day after, one of them, (Wright, who lately ran from George-town ) left the party, went into Launceston, and surrendered – that on the 29th, Collier surrendered, having a cut across the neck, and his left hand much shattered: — he states that the night after the robbery alluded to, Browne & Wright left the party — that Septon, Hillier, & himself remained at a hut behind Gordon’s Plains, where in the middle of the night, Hillier with razor cut the throat of Septon so dreadfully as to cause his immediate death — that Hillier then attempted to cut his (Collier’s) throat, who, however, got out of the hut with a slight cut on the left side of the neck: upon which Hillier, who had possessed himself of the whole of the arms, took up Septon’s rifle, fired, & shattered much of the hand of Collier. It does not appear that there had been any quarrel; And Hillier’s motive for killing Septon, and attempting to kill Collier, can only be supposed to have existed with a view to obtain the reward offered for them. Since this affair Coine, another of the old bushrangers, has given himself up, and is in confinement at this place; and there remain now at large, Howe, Watts, and Browne, for the whole of whom rewards are offered. — [See Proclamation.] (Footnote 3)

More in 1817:

George Gray, who murdered JOHN EVANS at York Plains, as adverted and noticed in our last week’s Gazette, was this morning brought in a prisoner by a guard of the 46th regt. and lodged in the gaol. He was taken on the road to Launceston, by Corporal GREEN, of the 46th alone; a circumstance highly creditable to him.

A soldier named Berbridge, who shot his comrade in the Barracks at Launceston a few days ago, was brought in by the same escort. The Coroner’s Inquest in this case was Wilful Murder; but he declared his ignorance of the musket which be fired being loaded : on the other hand, it is stated by two witnesses, that he had been told it was loaded with ball. (Footnote 4)

It was a different and dangerous world. Yet along with murder, assault, mental illness, severe alcoholism, floods, famines and much rain the two settlements continued to grow. Most settlers received supplemental supplies from the government but were beginning to make a go of it alone. This was Ellen Cummings’ world. By her teen years she had experienced the Rum Rebellion, a move to a new colony, home invasions and her mother’s tragic death by drowning in a flooded river in 1820 when she was aged 11. There had been little safety and maybe not much happiness in her world. Shipping records indicate that her two older brothers – John and James – spent more time away from the family home than there once they were old enough to escape. The Cummings family had money and a good position in society, not to mention a sense of entitlement which passed from father to son for several generations. But Ellen was a girl in a family which did not afford equal status to women. She missed a lot of the education and opportunities which her brothers received. No doubt by the age of 18 in her lonely world she needed a protector.

Southern entry to Launceston 2014. This is probably the same hill from which the 1812 description was made. The rivers Tamar and Esk are temporarily hidden by the left hand cutting.

Given the copious records, letters and official engagements of the Cummings family, it would be surprising if the George Richards that we have gleaned from the records was an equal match for Ellen. The Cummings family were well connected in Ireland and England, had married into a very wealthy family on the Isle of Man, had some lucrative enterprise in India and managed to wriggle out of a whole lot of scrapes which would have resulted in a destroyed life for a ‘lesser’ man. Ellen seems to have been a forgotten and unregarded child. Her father was only concerned about the boys. Thus somehow she met an illiterate convict approximately ten years older than she and the two of them made a match of it.

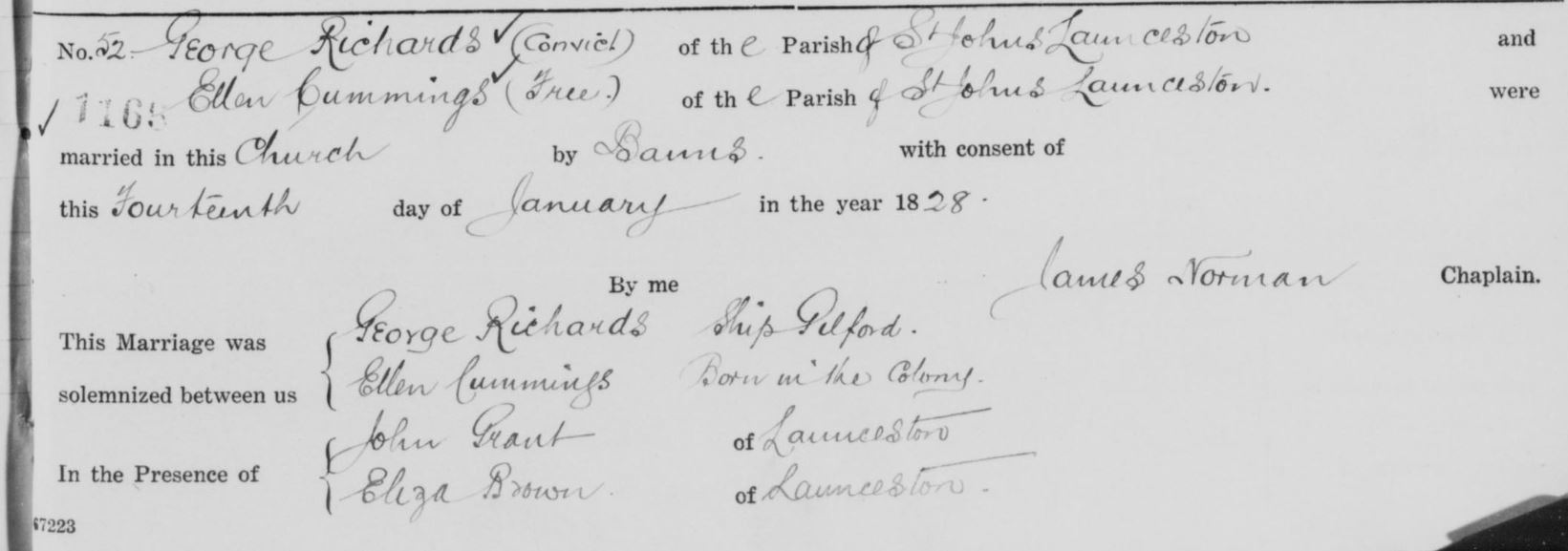

Here’s the marriage record:

Marriage record of George Richards and Ellen Cummings (Footnote 5)

Civil registration started in Britain in 1831 and that requirement was sent to the colonies at the same time. Three years earlier, in 1828, we have only a church marriage record. There was no consent sought for Ellen despite her tender years. Eighteen was not adulthood in 1828 so she should have required the permission of either parent or if an orphan, of a guardian such as an elder brother, but in this era officiating ministers were hard to come by and they undertook a multitude of religious ceremonies. I have not managed to trace the witnesses but hopefully I’ll find them one day.

Many of the details on this certificate are correct. Ellen was born in the colony – well, in a neighbouring colony – and she was free. So presumably the record is correct in identifying George Richards as a convict. I’ve never heard of anyone impersonating a convict. It is therefore logical to assume that George Richards was a convict who arrived on a ship called the Pilford. Which doesn’t exist.

There were 9 convicts named George Richards transported to Tasmania and another 12 so far identified as transported to New South Wales. The common theory among family researchers is that he arrived on the ship ‘Guildford’ in 1819. There was indeed a George Richards on this ship. The convict from the Guildford was a butcher. Our George is also a butcher. So this fits. But we don’t know for sure and in one place at least, it is recorded that the convict from the Guildford died in 1825. There was indeed a convict named George Richards who died in 1825 but not ours. The record is all out of order and seems to have been rewritten from another record.

George Richards was tried on 4th March 1820 in Chelmsford, Essex and found guilty of larceny. He was sentenced to death which in the usual way was transmuted to transportation 14 years. He was placed in a hulk named Leviathan at Hampshire, from whence he was removed to the Guildford and arrived in Tasmania on 10th October 1820. He received a ticket of leave at some early date. In 1824 he stole something which I cannot read from the factory of William Smith in Launceston so he must have been in town then. He was in trouble again in 1826 for being out after hours. Which brings us to the date of his marriage, of which there is no mention in the convict record.

The eldest child of George and Richard was my own ancestress, Frances Ann born 2nd January 1829. She was baptised in March 1829 at St John’s Anglican Church in Launceston.

Baptism of Frances Ann Richards in Launceston Tasmania

George’s convict record contains a misdemeanor of being absent from muster on 26th January 1829.

From this point, all we have is a handful of baptism and civil birth registration records. Combining the existing baptisms with later records the Richards family so far consists of:

George’s ticket of leave was suspended for six months on 11th March 1831 for some unknown reason, only a few months after the death of his first son George.

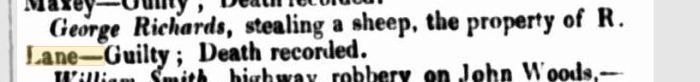

In 1833, George was charged with sheep stealing, an offense which still brought the death penalty in those days. (Footnote 6)

So, does this mean he died? It seems not, because although his convict record also states ‘Death recorded’, the entries go on. In fact, his convict record states that he received his free certificate on 7th Feb 1834, at which point he was still in jail awaiting trial. This is very very unlikely!

However, no registration has been located for the children born between 1833 and 1839. We know of them either through their marriage and death records or through DNA matches with their descendants. The town of Launceston was growing rapidly at this time. Whether they lived in town or somewhere very rural is not known.

In 1838 George was arrested on suspicion of felony but there was insufficient evidence to bring the matter to trial. On March 14th 1840 he was arrested for being drunk and disorderly. There was another felony in Sept 1840 and a third offence on 3rd October the same year due to entering the constables’ huts while drunk. For this offence he was sentenced to 10 days hard labour on the roads. It didn’t help. On the 31st October 1840 he was in trouble again for another felony but the case was dismissed due to lack of evidence. Possibly he’d gained a reputation.

After that final offense in 1840, the matter was allowed to rest on the condition that he move to the Hamilton district and remain there. It’s where the unruly ex-convicts went.

This fits with the movements of our Richards family. All the children from Eliza onward were born and properly registered in Hamilton. George appears in their birth registrations as a labourer, a butcher and finally a farmer.

On 8th November 1847, George and Ellen’s eldest child Frances married Edward Cox at St John the Baptist, Ouse. Almost ten years later in 1856, Ellen passed away, the cause of death given as dropsy. The family split up, some of the children leaving for the now thriving colony of Victoria where fortunes were being made in the goldfields and there was work for everyone.

As required, George remained in Hamilton. Richard and Matilda moved to Victoria. Harriet married a shepherd of Osterley. The youngest four girls all married local ex-convict farmers. I’ve written often about the Ouse region with its early pioneers, that peculiar bunch of free-by-servitude men who lived almost as one with the bush and could comfortably spend weeks alone without missing human contact. The six Richards girls who remained in the Ouse region became matriarchs of six large families who still live and farm in the region today. But the sons moved away. One of the boys had a liaison with a local girl but there was no marriage. The resulting son grew up bearing his mother’s surname and his descendants also continued in the region.

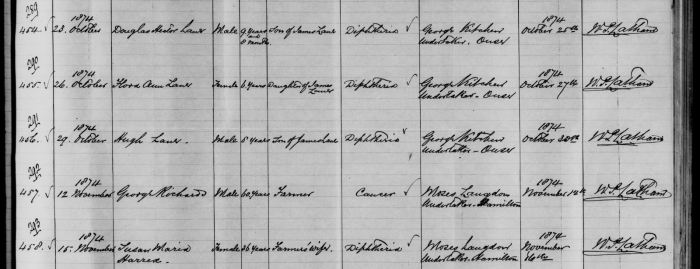

This has been a very long post, I know. George Richards ended his days amidst a diphtheria epidemic which took half his family. His daughters Frances and Susan plus his grandson Edward George Cox all died within weeks of each other. George’s death was attributed to cancer. Possibly this was so. Possibly he had cancer but the diphtheria was taking hold also.

Here is his death registration. His daughter Susan is the entry immediately after his. (Footnote 7)

To conclude, here is George’s grave. It’s a proper monument, worthy of a pioneer of the district who was also father-in-law and grandfather to most of the region’s farmers.

Grave of George Richards at St John the Baptist Ouse Tasmania

(Footnote 8)

Footnotes:

(1) By Lencer [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

(2) “GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL ORDERS.” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842) 11 January 1812: 1. Web. 2 Jul 2017 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article628393>.

(3) “HOBART TOWN; SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 1817.” The Hobart Town Gazette and Southern Reporter (Tas. : 1816 – 1821) 6 September 1817: 1. Web. 2 Jul 2017 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article652952>.

(4) “Hobart Town; SATURDAY, NOVEMBER, 1817.” The Hobart Town Gazette and Southern Reporter (Tas. : 1816 – 1821) 1 November 1817: 2. Web. 2 Jul 2017 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article653280>.

(5) State Archives of Tasmania, marriage records Church of England

(6) “CRIMINAL SIDE.—THURSDAY.” Launceston Advertiser (Tas. : 1829 – 1846) 20 February 1834: 3. Web. 3 Jul 2017 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article84774309>.

(7) State Archives of Tasmania, civil death registrations

(8) http://www.gravesoftas.com.au/municipalities/Southern_Tasmania.htm