Over the past twelve months, many useful Irish records have become accessible via the internet. Principle among them, at least for the history of Dillane, are the Irish Catholic Parish Records.

Our branch of this family has puzzled my cousins and I for at least fifty years. We always had a rich oral history regarding the Australian branch – they arrived in 1856 and became successful pioneers of the Cygnet district in the south east of Tasmania. Three brothers, transported as convicts for burning down a haystack. There is a blog trilogy regarding this line starting here. The first post is actually about the Woulfe family with the second and third focusing on Dillane.

But to summarize for those who don’t wish to read the earlier posts – Edmund, John, Timothy and William Dillane were all brothers in Athea in West Limerick. All four married in Athea. Edmund, John and Timothy were arrested and transported and their name morphed into ‘Dillon’ via the convict records. William remained in Ireland where he raised a large family and kept the surname Dillane. The Athea parish records begin in 1827 and until the past year or so we could only rely on transcriptions of the data.

Luckily, those days are over! Here are a couple of very interesting details from the parish baptisms.

Baptism of John Dillane 05 Feb 1842 in Athea

Baptism of James Dillane 28 Oct 1843 in Athea

Baptism of Michael Dillane 14 Aug 1844 in Athea

In 1838, the most excellent Father Luke Hanrahan began work at Athea. Actually, I’m sure the others were excellent too. But Father Hanrahan was wonderful in that he added the residence of his parishioners as he wrote out the records.

The above three baptisms are for the sons of Edmund and William giving their residence as Glanduff. This marvellous detail has not come to us before.

Map of Limerick with relevant locations highlighted and added. Public domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABaronies_of_Limerick.jpg

This is a crowded map but it is hard to find one that can be legally used. Glanduff, the residence of at least two of our Dillane brothers, is the red dot in the far south. Athea, the place where their children were baptised, is the red dot in the upper left. Although not a huge distance by today’s standards, it is a distance of about twenty miles.

The townland of Glanduff -also known as Glenduff and sometimes Glinduff – was mostly the property of Eyre Massy at the time of these baptisms. It was and still is part of the parish of Monagea.

In the 1820s, a detachment of the 40th regiment was stationed at Glanduff and was later replaced by a detachment of the 42nd. Some very interesting stuff was happening there in the 1830s and 1840s.

The trouble with stepping a generation back – as we do in family history – is that we find ourselves at the end of a long piece of action. It’s like starting a movie in the last half hour. But for the sake of tracking the record it has to be done this way. So apologies if it gets confusing.

Most of us who research Irish ancestry will know about the conflicts which occurred there, the whole England and Ireland thing with protestants coming in and taking Catholic land. That’s an oversimplification of course. There were people possessed of the favour of one monarch who were given land that used to belong to the people favoured by the former monarch, regardless of their religion. There were people with money on all sides, including Catholic, who managed to keep their holdings and summon armies. Each county has its own stories, its own armies who fought its own enemies. It was a complicated thing. So to research ancestors in the county of Limerick, it isn’t enough to know a general history of Ireland. It helps to know the history of Limerick. It’s probably a life’s work really.

King John’s Castle – Limerick City taken by William Murphy 2011. CC 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/ Some rights reserved. No changes made.

The siege of Limerick (the castle/city of Limerick that is) occurred in 1691. The obituary of an elderly Woulfe in the 1920s (born circa 1830) stated that his ancestors had proudly served in the castle holding off the attackers. This is an indication that stories about that event were still part of oral history across the next few centuries.

The city of Limerick was an urban environment – by 19th century Irish standards – whereas the area to the west was wild with very little infrastructure. As late as 1820, many of the roads lacked bridges and were impassable after heavy rain. There wasn’t much travel happening at all. There was a lot of poverty and a lot of crime, some of it deadly.

The Dublin register reported the following on 09 February 1822:

Four men of the 40th Regiment, who were left at Glanduff to give up the Barracks, were surprised on Tuesday morning. While two were carrying the furniture up to Glanduff House, a party rushed in suddenly, and overpowering those left in the Barracks, got clear off with the entire of their arms, ammunition and accoutrements.

It was a time of violent secret societies on a mission to defend the powerless Irish tenants against their oppressors. Two of these societies were the Rockites – led by a succession of ‘Captain Rock’s – and the Whiteboys who were based in Cork.

The same newspaper gave the following reports amidst a large number of other incidents.

A party of Whiteboys went into Drumcolliher on Monday night, firing shots, after which they retired, saying they were not sufficiently prepared. On Tuesday night they attacked several houses, and succeeded in getting twelve stand of arms from different inhabitants in the town.

On Monday night another party went into the town of Abbeyfeale.

Wednesday, at two o’clock in the day, three men in women’s apparel went into a field at Dobile near Rathkeale, and shot a horse engaged in ploughing, belonging to a farmer named Scully; the three fellows announced themselves as Lady Rock and her suite, and mentioned that if Scully did not leave the country they would serve him as his horse.

On the above map, Drumcolliher is to the right (the east) of Glanduff. Abbeyfeale is close to Athea. Our Dillane ancestors were living right in the middle of all this action. Knowing their future and the personalities of later Dillanes, they were probably a large part of it. There are disputed reports that the first Captain Rock was one Patrick Dillane of Croom who to avoid capture apparently escaped into the wilds of West Limerick in the 1820s.

It was a long and convoluted trail which led me to Croom – in fact, a DNA match with another Woulfe descendant. She descends from a Sheehan of Shanagolden who married a daughter of Patrick Maurice Woulfe. They were actually married in Athea, but since her husband’s parish was given as Shanagolden I followed them in the records and began to find more Dillanes including the following marriage.

Marriage of John Dillane to Maria Wolfe of Athea at Croom 15 June 1808

I am fairly sure that this is our line and that we have two generations in a row of a Dillane marrying a Maria Woulfe. It would help explain why so many distant cousins are showing as a bit closer than they should. Why Croom? It’s so far away that I still feel the need for another corroborating detail to confirm it. I was pretty sure given the children’s names that the mother was going to be a Bridget, which is not borne out by this record. That said, they all have an elder daughter called Mary as well so this fits too.

I’m also pretty sure that I have found John’s baptism and a couple of his siblings were also married in Croom, which makes it more likely that this is he.

Baptism of John Dillane at Monagea 30 Dec 1789

So here we have another few useful details, including the residence of Meenileen – known to us also as Meenoline – the home of a well established branch of our Woulfe family. Meenoline is marked on the above map, just south of Sugar Hill. In the 1828 tithe applotment books, one Edmund Dillane can be found residing at Sugar Hill.

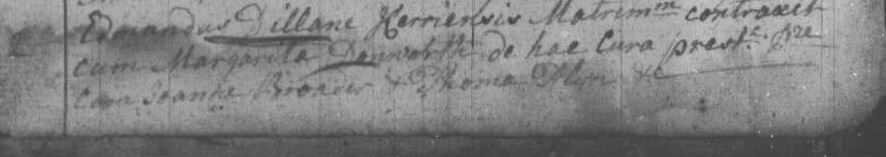

To hastily conclude this blog post since it is getting rather long, here is the marriage of Edmund Dillane and Margaret Dunworth.

Marriage of Edmund Dillane and Margaret Dunworth 15 Jan 1789 in Monagea.

I have found a few children now for Edmund and Margaret – as well as John, there are daughters Mary, Catherine and Julia (Juliana).

This will not be conclusive for some time yet, until I can piece the whole extended family together and figure out why a Dillane from Monagea might have travelled as far as Croom to marry a girl from Athea. Maybe it was a runaway match? This was also the era of marriage by abduction, something else which the papers were full of. But it is all guesswork just now.

At the very least, I have a likely hypothesis for myself and other researchers to work from.