Once upon a time I completed a course in genealogy which included some units in writing fictional accounts of our ancestors’ lives.

This was very hard for me to do, after years of diligently verifying each fact a minimum of three different ways before including it in my tree. My very first piece of flash fiction felt wrong, as if I were disrespecting my ancestors’ memories. It was like gossiping about a neighbour, spreading false ideas about their motives and personality traits.

Since then I’ve discovered that hypothesis is a useful tool. The trick is to ensure that anything fictional is clearly labelled as such. Of course, the canny genealogist considers every piece of information as fictional until proven otherwise, but to be complicit in creating fiction – well, that’s a whole new uncomfortable ball game.

In the past few years, though, I’ve seen it used quite effectively. One example is in the late Nigel Triffitt’s wonderful blog about the Triffitts of Tasmania. He mixes facts with speculation and uses his prodigious writing talent to bring that early settler family to well rounded life. I’ve also found that some respected researchers create suppositional trees while trying to sort family groups from a specific record set – such as all the baptisms of a particular church. Again, the trick is to ensure that nobody with access to that tree thinks it’s the final result. And as already stated, the seasoned family researcher doesn’t believe other people’s trees ever. We all do the research over again ourselves to see if we come to the same conclusions.

So that’s the preamble. Most of this post is flash fiction about my 3x great grandparents Francis and Fanny Eliza Burleton. The question I set out to answer in my fiction was how they could leave their first born (only) infant son in his lonely grave and move all the way to the southern hemisphere. How did they feel about that?

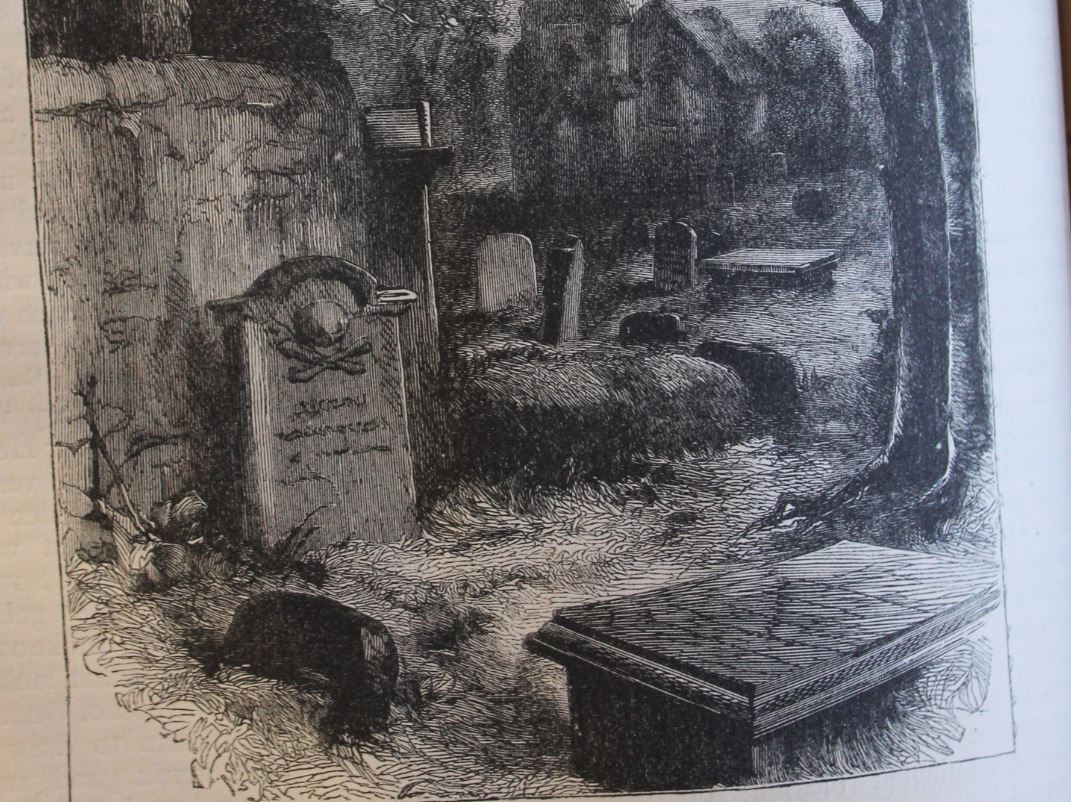

While it’s not ‘true’, I incorporated as many facts as I could. The family relations are correct. The cemetery is the correct cemetery. The personalities of Francis and Fanny Eliza are as correct as I can make them using their own voice via family papers and wills.

I like this couple so much that I wanted to share my vision of them with the rest of the world. Their story makes an epic tale of success in Australia tied up neatly with the success of Bowna and the beginnings of the iconic Hume Highway.

Two courageous young adults of good intellect. Both were poor relations amidst the solid wealth of their cousins in the Somerset village of East Harptree. Both had the capacity to be so much more. It must have been tough.

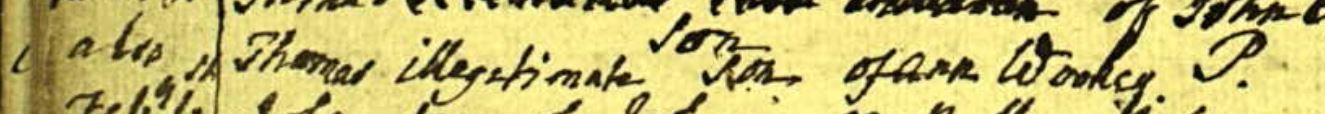

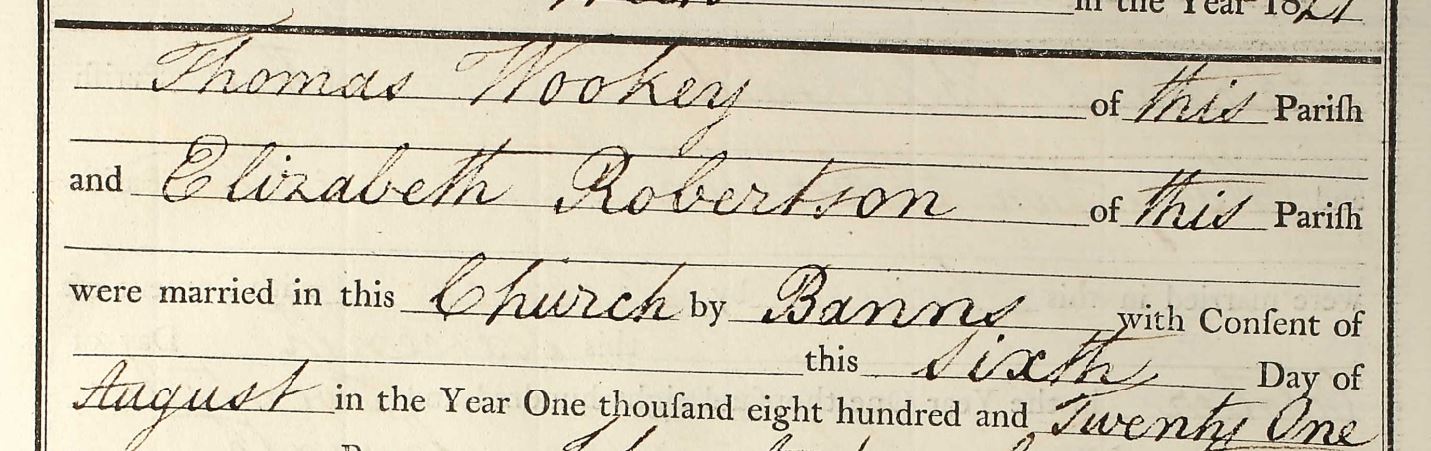

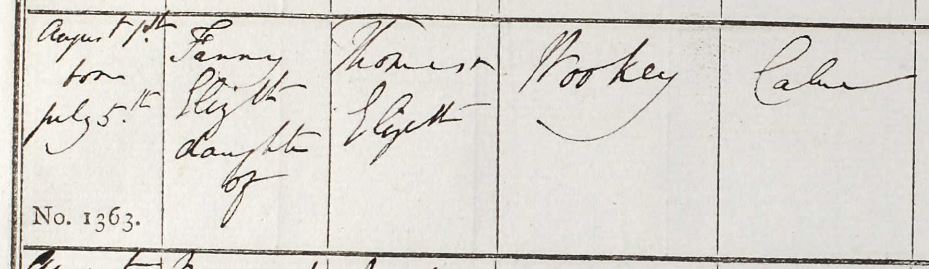

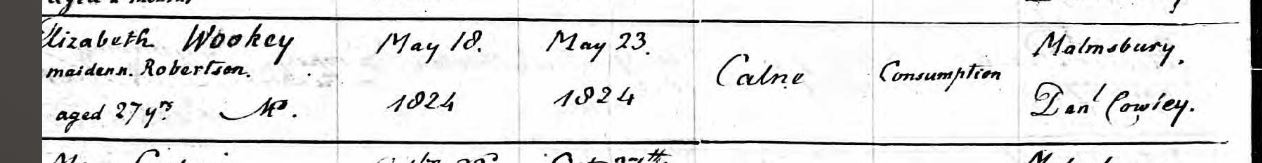

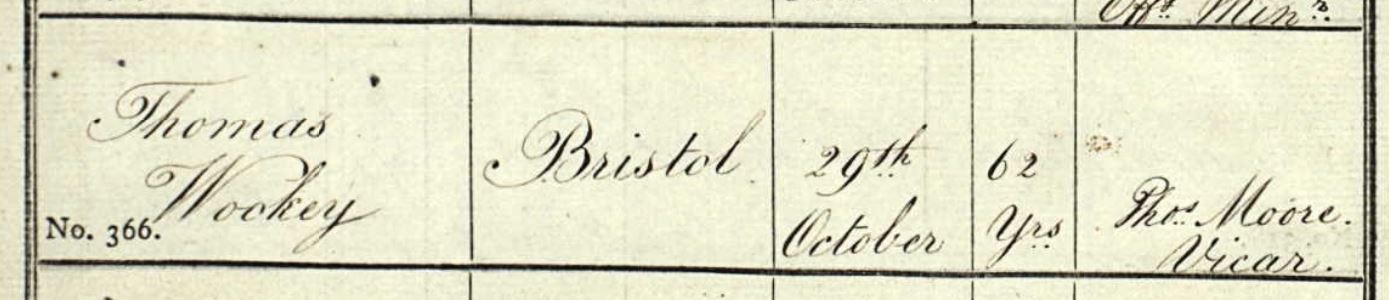

I’ve covered some ancestral background of this couple in previous blogs. William Burleton and Thomas Wookey are the fathers of Francis and Fanny Eliza respectively. I’ve written a little about Fanny Eliza and I’ve also touched on William’s father John Burleton. After marrying in East Harptree, Francis and Fanny lived in nearby Coley where their daughter Mary Anne and son Albert Edward were born. Albert lived for eight months. This fictional piece is set at his burial in East Harptree.

Fictional Piece – A Burial at East Harptree

On a balmy morning in spring when new leaves budded on the trees and robins fossicked for twigs to make their nests, Francis Burleton followed slowly behind a tiny coffin destined for the East Harptree churchyard.

Fanny Eliza, black clad and very contained, walked at his side carrying their daughter. His wife’s haunted poise wrenched the breath from his chest. Mary was settled deep into her mother’s arms, very aware that catastrophe of some sort had struck the family. She was good as gold this day, quiet as an old woman with her little toddler fingers wrapped in black mittens against the cold.

At the churchyard he waited with his wife and his brother Will, lost in thought. Would the sunny girl he had married emerge again? Or was she now a different creature? Could any of them be the same again?

Here was the grave of John Burleton, his grandfather. He remembered a solid man of stoic demeanor and poker face, the last of the old style of yeoman farmers. Church warden, local magistrate and of impeccable reputation. John Burleton had even entertained aristocracy at Eastwood Farm. His excellent husbandry added wealth to local importance. It meant something here in Somerset to be a Burleton.

But Francis remembered that time when he was just a boy where he had no place to be, overhearing a tirade of abuse hurled at his Papa by this great man. John Burleton with florid cheeks and booming voice in the parlour at Eastwood Farm. And his own Papa, six inches taller but cowed and silent, accepting the abuse.

“A bankrupt! A Burleton in the bankruptcy courts? How DARE you show your face on this property now! I might have known you’d throw it all away, boy, but I’ll be damned if I’ll permit you to take us with you.”

Even then, afraid to move for fear of being spotted, Francis had marvelled at the difference between the two men. His grandpapa so black and stiff. His father so ethereal, tall and thin with light wispy hair. His grandpapa with rigid routines and his papa with a new grand scheme every day. But Francis did not, back then, know what bankruptcy was.

That was just before the move to Wales escaping whispers and recriminations. Mamma staunchly supported Papa, as always. The Burletons never had approved of her and she was happier in Wales. Until the dreadful day that Papa was transported to the colonies as a common criminal. That day shattered all the family’s hopes, silenced their dreams and forced them to reassess their whole world.

It really was not Papa’s fault. He had set the Welsh town against him with his criticism and grand schemes, had upset the natural order of things as he always did. He wasn’t a criminal, but he had disrespected the property of others. They’d taken action, got him shipped off. It was a stitch up.

Francis and Will were brought back to Somerset, placed at Eastwood Farm with their Uncle Robert to learn good management. They were servants on the property that might have been their own had their father not been who he was. It was a heavy enough trial to endure. But how could they blame Papa for being himself? Papa was born that way, with some odd twist in his brain that denied him the gift of foresight. Papa’s dreams were more real to him than reality. And the fact was that Uncle Robert had taught them a great deal. They could now do what their father could not – keep a farm and family together, make it work for them.

As a bitterly cold drizzle settled over the churchyard, Francis caught the eye of his brother. Now Will was heeding the call for emigrants and leaving them. Heading off to the wild lands of New South Wales in search of gold and pastoral land. The thought pulled him back to the present and Francis looked round at the rest of the mourners waiting with him.

Uncle Robert stood alone, solid and poker faced just like a Burleton of old. He wasn’t happy with the funeral arrangements. Little Albert should have been buried in the Burleton plot, but Fanny Eliza had put her foot down and she was a Wollen.

Wollen. An old name, true aristocracy. They’d daughtered out now and Fanny’s mother had been one of the last. Francis had married her for herself, not her family name. Yet, she had a power over the Burletons that he could never have imagined and she was not in awe of them at all.

He watched her move quietly to her mother’s grave and place a finger lightly on the headstone as she always did. Just a quiet ‘hello Mamma’ to the woman who had died before her babies could come to know her. It was Fanny Eliza’s decree that her first born son would be buried here, with his grandmother to watch over him for all eternity.

The tiny coffin was lowered. Francis and Fanny Eliza cast the first sod. They watched their cherished son vanish from view forever. Francis had the distinct impression that Fan was burying her innocence in that little grave with her boy. When it was done she looked at him. Silver droplets of rain shimmered on her smooth dark hair. Serene. Peaceful. Determined. Changed.

“Will has the right idea.” She said. “We have nothing here. Mamma will care for Albert now.”

Francis looked at her in puzzlement.

Fanny Eliza looked across the churchyard. “I want to move to the colonies. This place is not good for children.”

Move to the colonies. Will had suggested it weeks ago and he now felt a stirring of curiosity. What might it be like?

But if Fanny Eliza had decided there was no question.

“Yes.” He looked solemnly at her. “Let’s do that.”

They walked across the churchyard to rejoin the mourners.