These are the final years of William Burleton, my 4x great grandfather, continued from Part II .

William died 177 years ago and we can’t know his true personality, but I’ve always liked him as he presents in the records. It’s clear that people in his own day didn’t know how to take him. Some thought him pompous and entitled, some just thought he was useless. Others seem to have liked him well enough. He was never completely without friends.

I see him as an impractical man, someone unsuited to daily slog. He had grand visions for his own future but was completely unable to manage his finances. That was his greatest downfall. I think he had pride in himself but that pride took a battering as the years passed, as he had more and more need to prove to both himself and others that he could be the man he had always believed he would become.

By 1836 he was in prison, awaiting transportation to the colonies to complete a seven year sentence. He was an old man now, aged 54, but of general good health and a skilled miller. There’s little doubt that he knew his trade well, it was the one thing that had saved him again and again.

On 6th April 1836, William Burleton and 324 other male prisoners were loaded onto the ship Lord Lyndoch for its second convict run to Van Diemen’s Land.

Up till this time, William may have hoped for a reprieve; may not have believed it could go this far. He was not the typical convict. He was twice the age of most of his new contemporaries, of good birth and well educated. He was not a Welshman but due to his arrest and trial in Wales his cellmates were all from that country and many still spoke their own language. His differences might have seemed relevant. There was every reason to stay optimistic, but nobody stepped forward to save him from his fate.

The barque Lord Lyndoch was captained on this journey by the experienced John Baker. The surgeon was James Lawrence. It was an East India Company ship, leased to the British Navy in the usual manner. Built in 1815, it was in good repair but not of modern design. It was an experienced convict transport, there was no reason to expect any problems on the voyage.

An outbreak of dysentery while still at Sheerness delayed their departure. The earliest entry in the surgeon’s log is dated 10th April. The first two victims probably brought the sickness on board and both died after a week of treatment. No captain was going to make a long journey with illness on board, so the Lord Lyndoch sat in harbour until the infection was brought under control.

A fortnight after William came on board, they were cleared to leave. The ship departed quietly for Deal off the coast of Kent, its departure scarcely rating a mention in local papers.

Deal – arrived the ‘Lord Lyndoch’, Baker, for Hobart Town …

Globe 20 April 1836 p4 Naval Intelligence

Deal – the ‘Lord Lyndoch’, for Hobart Town, and several others, outward-bound, remain.

Globe 22 April 1836 p4 Naval Intelligence

On 24th April the Lord Lyndoch finally put out to sea. They made good time for an old ship, the whole journey taking 118 days. Conditions on board were stable, a small amount of jaundice and scurvy troubling the prisoners but the surgeon took quick action. William Burleton – recorded in the convict register as William Bourleton – was not treated for any illness on the journey.

There are very few references to the ship as it traveled, but they seem to have taken the usual route down the west coast of Africa, stopping at the Capetown for supplies. The only report is accidental, part of a conversation between rival newspapers in the colonies.

Bent’s News and Tasmanian Three-Penny Register (Hobart Town, Tas. : 1836 – 1837), Saturday 6 August 1836, page 4

The Lord Lyndoch arrived in Hobart Town on 20th August 1836 and the arrival was reported in pretty much every paper in the colony.

Hobart Town Courier (Tas. : 1827 – 1839), Friday 26 August 1836, page 3

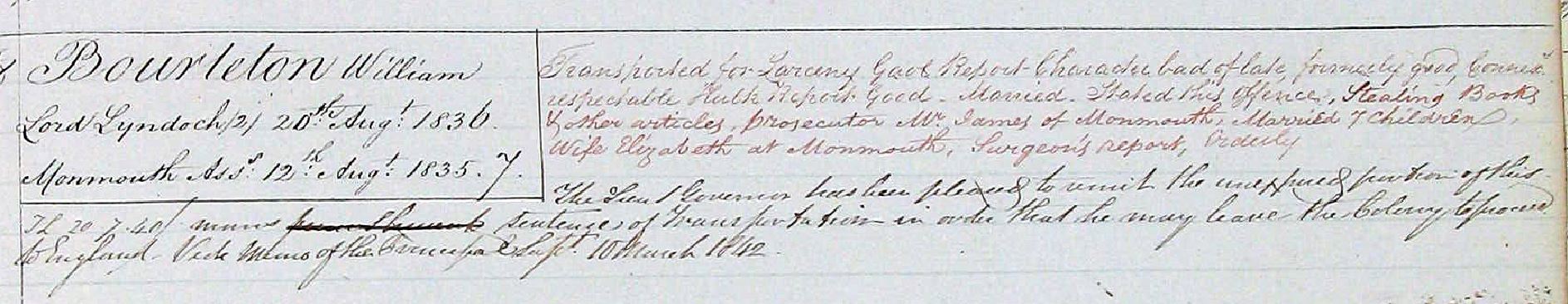

William’s conduct report is very short, but enough detail is given to track his life after arrival.

CON31-1-3 Image 106 page 154

Transcript of details above: Transported for Larceny,

Gaol Report: Character Bad of Late, formerly good, Connections Respectable, Hulk Report Good, Married, Stated this Offence: Stealing Books & Other Articles, Prosecutor W James of Monmouth, Married 7 Children, Wife Elizabeth at Monmouth, Surgeon’s report Orderly

You don’t often see ‘Connections Respectable’ in these records. You might see ‘good’, or ‘bad’ or often ‘indifferent’. But ‘Respectable’ probably means that William was telling people of his good birth and early prospects. He may have been negotiating for an assignment suitable for his position in society. Of course, position in society was officially gone once one became a convict, but in reality well born convicts still had some influence.

His name often appears beside Jenkin Jenkins’ in nonalphabetized records, so I think the two were friends.

His Description List is as follows:

State Library of Tasmania CON18/1/13 Page 284

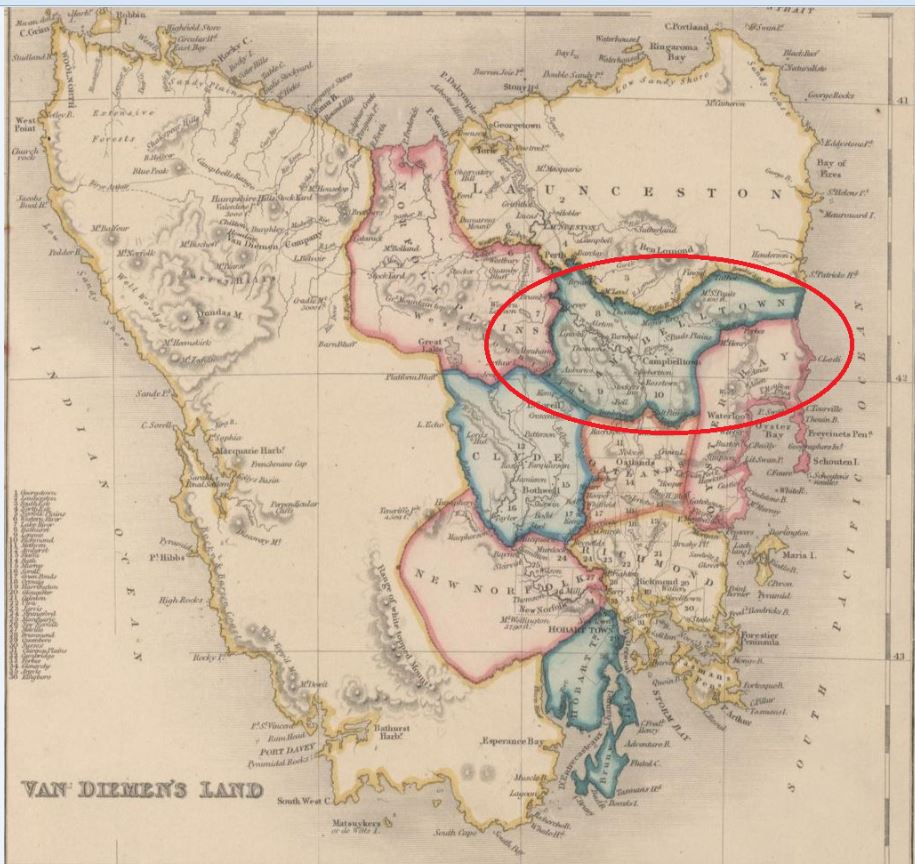

The British prison system was tasked with finding any skill that William possessed which could make him a useful resource. I really doubt he called himself a ploughman or a farm labourer. He was a Miller, that’s what he always said. But the colonies needed farm workers so any farm experience made him worthy of transportation. As it turned out, Van Diemen’s Land needed millers as well. William was assigned to settler Andrew Gatenby who had land at the Isis River north of Campbell Town.

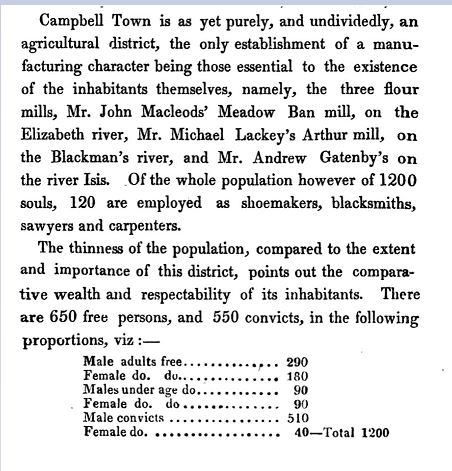

This description of the region was published four years before William’s arrival and references the mill in which William worked.

We don’t have much detail of William’s daily life here, but the absence of notes in his conduct report suggests that he settled well. He coped with the cold and the bushrangers and the different types of grain. No doubt he wrote letters back to Wales and perhaps to Somerset as well, but if so, none have survived.

He received a ticket of leave in 1840 and letters written to the Lieutenant Governor in 1842 by Andrew Gatenby and John Gellibrand – two very influential men in Van Diemen’s Land – refer to William Burleton as a man who has contributed to the establishment of the settlement. Both men recommend him for an early pardon and request that he be allowed to return to his family in Wales.

It’s another indication that his inability to handle money was the root of all his troubles. While he was not required to manage finances he achieved very well.

The final part of his conduct report (above) states:

“The Lieut Governor has been pleased to remit the unexpired portion of this man’s sentence in order that he may leave the colony to proceed to England”

Conduct report for William Bourleton State Library of Tasmania

CON31-1-3 Image 106 page 154

It must have been a great moment for William. Finally he had the respect of some capable men – Gatenby and Gellibrand – and he might have learned some practicality during his time in the colony. But he was now aged 60 and clearly just wanted to go home to his family.

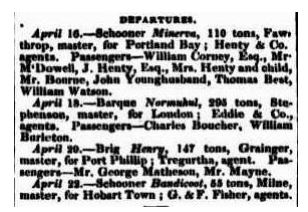

He booked onto a ship called the Normuhul, a small vessel leaving from Launceston for London on 20 April 1842.

Exactly six years earlier he had stood on the deck of the Lord Lyndoch as it waited at Deal, had probably looked across to the British shoreline and wondered if he would ever see it again. Now, no doubt, he stood on the deck of the Normuhul and looked at the forests along the Van Diemen’s Land coast. Probably, he was promising himself that he would never return. But maybe he intended to fetch his family and bring them back? Many did exactly that.

I haven’t found a picture of the Normuhul, but I like to think it was a pleasant boat since it was part of William’s almost triumphant return. He was the recipient of a full pardon, he was still a legitimate British citizen and he was going home at last.

It seems absolutely tragic that he didn’t get there. He’d probably written a letter telling Elizabeth that he was coming back. But it just wasn’t to be, the William Burleton streak of bad luck had returned.

It took me years to find William’s death. I knew that Elizabeth called herself a widow in the 1851 British census, but I never could find when he actually passed away.

Here it is in a section titled ‘Shipwrecks and Casualties at Sea’

South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), Saturday 13 May 1843

The wreck was never recovered so we don’t know exactly where they went down. This was a misfortune entirely outside of his control for a man who always tried so very hard and failed so often. But he died with a clear record and at long last, leaving a good reputation behind him in Van Diemen’s Land.

Some of his family remained in Monmouth and their descendants are still there today. The rest returned to Somerset.