A lot of people have written very well about this. It impacts every researcher who uses DNA matching and everyone has a different opinion. Which interests me as much as the event itself.

I’m no kind of expert. This post is about what the change means to me and the way I do my research.

So for context – if you do a DNA test with Ancestry, and you have a family tree on their site, and you link your DNA test to yourself in your tree, then Ancestry will compare your tree with the trees of your matches to see if it finds any common ancestors. It will then highlight these common ancestors so that you can compare the trees and see if you agree. If it’s correct then yes, you’ve found a cousin.

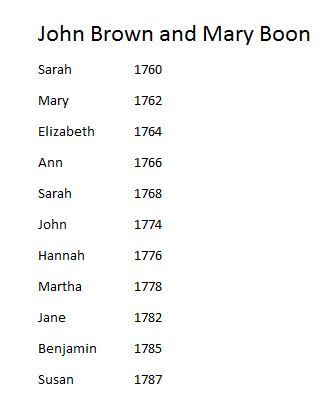

It looks like this:

The above match is female, has a linked tree with 79 people in it, shares 7cM with me which is a reasonably small match, and apparently has a common ancestor. I can then click on the tree link and check it out.

The suggestions go all the way down to myself and my match. I’ve cut off the lower ones for the sake of privacy.

I have several matches to these ancestors, one of whom is through an ancestral daughter who I’d never managed to trace. The common ancestors are definitely the same people. The paper trail verifies their movements. These are genuine matches. Two share 7 centiMorgans with me, one shares 6 centiMorgans.

Is it actually a DNA Match? I don’t know, because Ancestry doesn’t give us access to a chromosome browser. To me, it doesn’t necessarily matter. Well – it does and it doesn’t.

And this, I think, is where all the confusion and different opinions and complexity comes in.

On Family Tree DNA you do get a chromosome browser.

I picked two matches who also match each other and here’s the place that we all match. Same place on the same chromosome, that’s what makes it a real match. Of course, chromosomes are paired – there are two ‘number nine’ chromosomes, one that we got from our father, one from our mother. It takes a bit of comparing with known matches to determine which of that pair these matches are actually matching with. If they match in the same place on different chromosomes they are not a match, but if it’s the exact same one they are. Working it out can be done, and many of us enjoy that game.

If you can figure out which ancestral line a specific segment was inherited from, that’s useful. For the above ancestor John Peard and his wife Bridget Woodley, I could look for that precise segment match among the unidentified hordes who also match me, but haven’t got a tree – and I could say positively ‘This person also descends from John Peard and Bridget Woodley’. Or maybe I could say, ‘this person descends from a sibling of John Peard and Bridget Woodley’.

My example match is so far back, it takes a solid paper trail and a lot of time and a lot of matches with trees to even begin. I’ve been lucky with this one.

This is Ancestry’s ‘thrulines’ facility. It has pulled together every DNA match with those same ancestors – or with enough ancestors that some tree in the system can bridge the gap – and it shows them to me. I have twelve matches on Ancestry who also descend from John Peard and Bridget Woodley. It’s quite amazing, because I rarely stumble across Peard researchers. I’d never have found these guys were it not for DNA matching. I have another four on FtDNA who haven’t tested with Ancestry at all, including one who descends from John Peard’s brother. That’s sixteen matches back to my 3rd/4th/5th great grandfather in this family line.

The one on the far right is a genuine match but their tree is slightly wrong, so they don’t show up in the correct place.

Onto the harder ones:

The magic number in Genealogical DNA is 7 centiMorgans. Some scientists determined several years ago that a match of this length (or longer) is more likely to be genuine. If you go smaller, some will be genuine, some might not. And then you get what is called a ‘false match’.

I hate that term. It’s misleading. But that’s what everyone calls it.

A false match isn’t actually a false match. It’s not like a ‘false positive’ in a medical test. It’s not saying there’s a match when there isn’t. There really is a match.

Someone else’s chromosomes could have accidentally come together in the same sequence as yours – that can happen, and since they don’t share your ancestors at all it’s useless to spend time looking for a connection. This is the most genuine form of ‘false match’. It’s like the two boys in ‘The Prince and the Pauper – they looked identical, but they were not actually related at all. In a perfect world, there’d be some way of spotting these and filtering them out so what we could see were just the real ones.

But there are other sorts of ‘false matches’. You might match in much smaller segments from different ancestors that have ended up next to each other so it looks like a bigger match than it really is. A 4 centiMorgan segment from your father’s side next to a 5 centiMorgan segment from your mother’s looks at face value like a 9 centiMorgan match, until you check the matches in common. With the massive endogamy coming out of little villages across the world where cousins married second cousins and their children did the same, century after century, you end up with a lot of third/fourth cousins emigrating to the Americas or Australia or Canada who actually share enough DNA to look like first cousins. So we can look closely related when we aren’t.

That is, if I have an ancestor from West Limerick and you do too, we’re likely to have a very small DNA match whoever our ancestors were. And if I have an ancestor from Isle of Harris in Scotland and so do you, we’ll share DNA from there too. Just think how many people must have one ancestor from West Limerick and another from Isle of Harris. If those two segments are next to each other it looks like a different match to the one it really is.

It is still a genuine match though, really. Just way too hard to identify, and there’s always the chance that one portion is an accidental resemblance even if part is by descent. That one takes some untangling.

The next ‘false match’ is where the match has come down unchanged for so many centuries that the common ancestor is way before written records. This happens more often than anyone first imagined, and those segments are known as ‘sticky segments’. Since they have come down unchanged to so many people, you end up matching thousands of people who seem like fifth cousins but are really twenty fifth cousins. You’ll hear this multi-match chromosome region referred to as a ‘pile-up’ region.

Once again it’s a genuine match. But at this point we can’t use them. Nobody has the trees. I think in time we’ll get there, with enough people testing, enough records coming on line, enough chromosome painting. But not yet, and the process is fraught with error. So for now it’s a ‘false match’.

That’s the background.

DNA testing at Ancestry has really taken off. The site is groaning under the strain of all those testers, stuck at home now due to lockdowns, isolated and diligently exploring their match. Site response times are very slow. We often get error messages saying their backend servers are overloaded. It can’t go on this way.

So they’ve decided to remove all those 6 and 7 centiMorgan matches, because most are ‘false’. And the remaining 8+ matches will be far clearer.

So, what do I think about that?

A lot of people are utterly appalled. Even more people, I think, are happy about it. My knee jerk reaction was horror, because I hate to let anything go before I’ve had a chance to look at it for myself.

Now, I’m lucky. I come from Tasmania, a small island settled by convicts and soldiers. Every step my immediate ancestors took was recorded. Not only that but the records were deemed to be part of our heritage and were digitized and made available to us all for free. Civil registrations, convict files and newspapers. And being an island, all entry and exit was recorded too, in shipping records. We have excellent paper trails back to England, to those 7th/8th/9th great grandparents. So we – like most others – can really make use of small matches. But most people can’t. So to most people, those tiny impossible hints really are ‘false matches’.

I would prefer that it didn’t happen so soon, but they just might be right. In some respects.

I have a total of 38,047 matches on Ancestry. 410 are close matches (fourth cousin or closer). I know just how I connect to every close match that has a tree with the exception of four, and for those I at least know the region/ancestral branch. I can take a guess at many close matches without trees, but a few of them are a complete mystery.

What would I have lost had I never looked at my 6-7cM matches?

Actually, a lot!

I have identified twenty cousins through 6-7cM matches. Some were the Peard matches mentioned above. Another is the sister of my Irish Catholic ancestor Mary Woulfe of West Limerick, born in Sugar Hill at the cusp of parish records. Others are descendants of the Brown family, subjects of my last blog post.

Yes, some of my most exciting discoveries have been made through matches at this level. No, I’m not sure if they are DNA matches, but DNA matching has brought me paper-verifiable matches that I’d never have found because they moved to districts I could not have predicted.

So if you want DNA purity, then yes, this is probably the best idea. And Ancestry’s common ancestor feature only works back to about eight(?) generations, if you match at the ninth you have to put in the legwork yourself and look at trees, search for names. It’s a good idea for Ancestry, they can reduce their server overloads and keep us genies focused on more accurate data, not screwing up our trees making fake cousins fit when they don’t. I get it.

All the same, I wish I could have looked through my 30,000 or so 6-7cM matches before it happened. But if I’ve missed some amazing breakthrough, I’ll never know. So I’ll let it go.

It’s a pity, but it’s not the end.