Recently the South Australian prison records were digitized and made available on Familysearch and I’ve spent some time browsing the early years.

A fascinating part of the Adelaide prison records in the 1840s is that they state where the prisoner came from and what year they came to the colony of South Australia. There are some crimes that appear regularly, the main two being 1) refusal by an indentured sailor to return to his ship and 2) drunk and disorderly. Sometimes there were six or seven men from the same ship refusing to return, and often those sailors came from countries outside of Great Britain. One day I’ll explore maritime history in South Australia. I’ll add that to the list.

So, I was browsing the prison records and pondering on such crimes as ‘obstructing the footpath’ and ‘damaging melons’ and I started looking at the places of origin of the prisoners. That’s when I noticed how many ‘drunk and offensive behaviour’ crimes were committed by people from Van Diemen’s Land.

I’m sure everyone knows that Van Diemen’s Land is the primary focus of my research (closely ahead of Munster). So I started looking in the Tassie records to see who those people were, thinking they might have been former convicts.

I was right. Most of them got their conditional pardon and hightailed it out of the state through the late 1830s. It’s too early for the gold rush. I don’t know if they wanted a fresh start in a place requiring labour, or if they were trying to get back to England and just trying to save up for their ticket. By the time we’re into the 1850s there are prisoners from Port Philip as well, plus a couple from Sydney.

Yep, deeply engrossing stuff.

The Colony of South Australia

The colony of South Australia began officially in 1836. It was founded on the notion of free settlement by colonists who could either support themselves financially, or bring some skill with them that the colony required (which meant they could support themselves financially).

The colony was wanted by British folk who wanted a respectable home – ie no convicts, no slave labour, no suss religion – that sort of thing. People who wanted to emigrate, but wanted to emigrate to a place as civilised as the one they had left.

The colony version of a gated community, in fact.

Some people did ascribe to that ideal, but the whole scheme laid itself open to corrupt absentee landlords. A lot of dodgy practices took place such as applying for a land grant in a baby’s name to increase one’s holding, purchasing all the land along a creek so that landlocked grantees would go bankrupt and sell up cheap .. the kind of stuff you see in American Westerns with squatters and their hired gunhands.

The first settlers set foot on ground near Port Adelaide in 1836; just a couple of boatloads.

But with all its problems, some ethical and enlightened minds came out to help set it all up. It wasn’t all bad.

By 1838 the colony had a population of approximately 6,000, with maybe half of them in the designated principal port town, Adelaide. Colonisation started along the coast; the inland was too hot and dry and arid. A flourishing port town began on the Fleurieu Peninsula to the east of Adelaide. Others began on peninsulas to the west: the Yorke and Eyre Peninsulas. Travel between those growing towns was by boat.

Despite it’s lofty and exclusionary ideals, the colony of South Australia attracted ex-convicts and absconders from all over. It was something they hadn’t expected; something they had to find a solution for after the fact.

Dismayed by the need to do so, the administrators of South Australia designed and built their prison very early on; it was taking prisoners by late 1838 and construction continued for some years after.

By 1847 the population of South Australia is estimated at 31,000. Adelaide was still growing, plus people had moved inland. Not far in, but white settlers could be found as far north as Clare (about eighty miles) and as far west as Mt Barker.

By 1849 the population reached 50,000. It’s hard for any town to assimilate that much change.

Now on to the subject of this post ..

The Incarceration of Isabella Anderson

Isabella Anderson is an early female arrest in this particular register. Aged 41 years and single in 1848, she was found guilty of being ‘drunk and disorderly in Morphett Street’ and placed in prison for ten days. Her place of origin was Van Diemen’s Land and she came to South Australia in 1838.

I didn’t think that much about her until her name popped up again, just a few weeks later (1b).

“Common prostitute using profane indecent and obscene language in Hindley Park.”

She pops up again and again. It’s obvious she had a problem with alcohol, and struggled to keep a roof over her head. I started to feel sorry for her; a middle aged woman in a strange place. Who were her friends? Was anyone worried about her back in Van Diemen’s Land?

I delved a bit deeper. By matching news reports with the prison records I learned that Isabella Anderson was a highly visible character in Adelaide in those days, and was known rather unkindly as ‘Scotch Bella’.

Isabella Anderson in South Australia

The earliest record of arrest I’ve found so far is January 1841, she was drunk and disorderly at the Port. There are only men in the register before that. Isabella has the dubious honour of being the very first woman incarcerated in Adelaide Gaol.

She might have laughed about that. She was a woman of spirit in those days.

Just a few weeks later she was arrested again, the record calling her ‘a prostitute being drunk in the streets of Adelaide’.

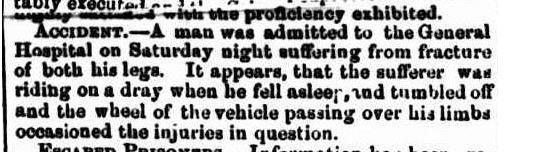

Newspaper reports about Isabella Anderson take us back to 1842, but it’s clear she was a known character about town before that: probably since her arrival in 1838. I’ve included these snips because they show some of Isabella’s personality.

(18th April 1842) (1)

Wed 1 May 1844 (2)

Wed 1 Jan 1845 (3)

A long time ago, I read some instructions on taking oral histories for a family history group. One of the suggested questions was ‘what are some colourful characters that you remember around town?”

The question was designed to draw out descriptions of people like Isabella Anderson. Not to ridicule, exactly, but with a failure to understand that they often did not live that way by choice. It seems like choice, because they choose it. But for many on the streets in the past and undoubtedly in the present, it was like choosing to sit on a stone floor vs sitting on hot coals. A choice between something bad or something worse.

In 1840s Adelaide, nobody knew what to do with “Scotch Bella”.

1 May 1845 (4)

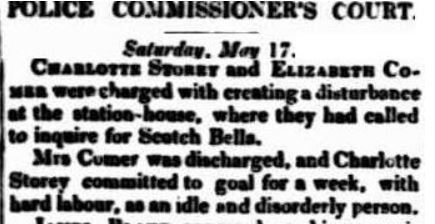

17 May 1845 (5)

21 May 1845 (6)

And so it goes on, chronicling Isabella Anderson’s descent into poorer physical and mental health until in mid 1846 we reach this event (7):

There’s a break after that. Isabella seems to have spent three months in the lunatic asylum before she was deemed cured and released to the world again. She went straight back in (8).

After this arrest she seems to have had another spell in the lunatic asylum, following which we get the spate of arrests in the prison registers shown above.

From this time there’s a change in Isabella’s mood. She’s not so happy. She starts thinking of Van Diemen’s Land as home. She’s clearly ready to leave South Australia now.

9th March 1848 (9)

Old lady? Isabella Anderson was forty three. Even by colonial standards that didn’t make her old. Most women were still having their last babies at this age, working in the fields, nursing family members, cooking and cleaning .. I expect it’s an indication of the impact of Isabella’s hard life. She looked old. She was over everything. She was feeling very, very alone.

27th May 1848 (10)

They didn’t send her back to Van Diemen’s Land. They just incarcerated her for another few weeks and then released her.

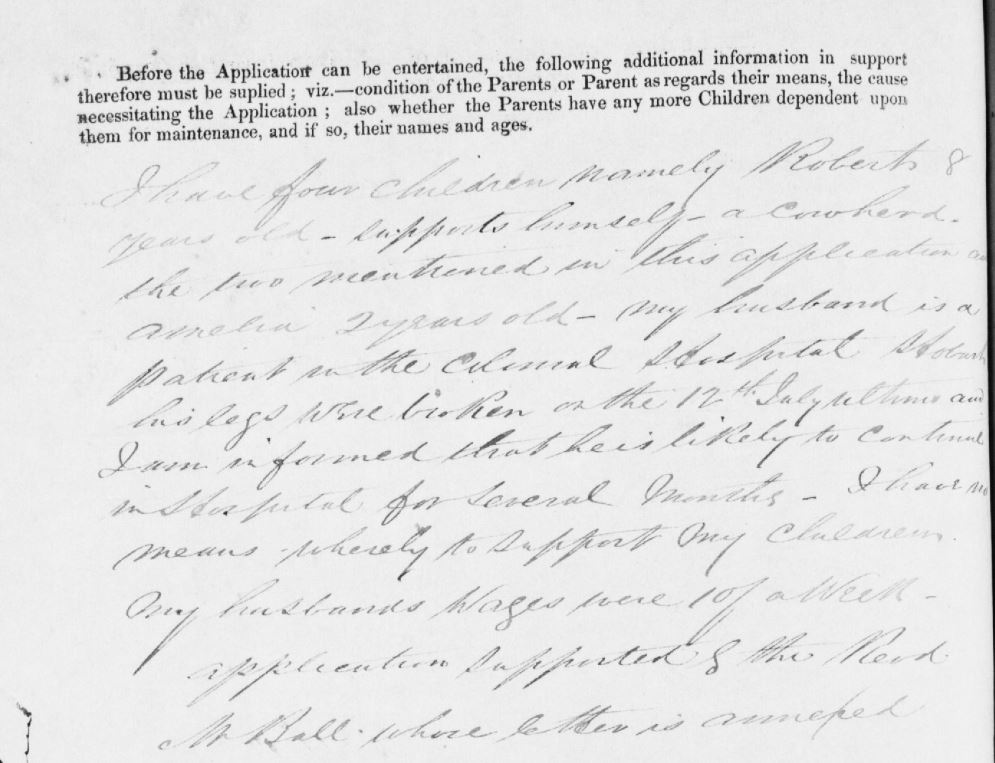

By this time I was quite invested in poor Isabella. I wanted to know how she ended up in that position. How was it that she was in her forties and single in a world where there was always some man to take a bedmate into his home? Fair enough, by the time she was in her forties she was addled and mentally damaged, but had she always been that way? She got to South Australia somehow, and Sergeant Lorymer said she was capable of work, he’d seen her do it.

If she was capable of work of any sort in a colony where women were in short supply, why was she single? And was she actually Scottish?

I can now answer some of those questions. Here’s the full story of Isabella (Bell) Anderson as I understand it.

NOTE: I should state here that I seem to be the only one following this connection for the Bell Anderson discussed next. It bothers me when that happens, it can mean I’ve missed some vital detail. But I’ve looked at the alternatives and I’m confident they can be eliminated. This is still the most compelling match for Isabella. (See section below blog for discussion of these alternatives)

The Whole Story

Isabella was born on 23rd December 1804 in a place called Dysart in the Scottish county of Fife. Her parents were Robert Anderson and Margaret nee Bruce, and she was the sixth child of eight. There’s few clues about her childhood. All of her siblings seem to have lived to adulthood.

She was baptised Isabella, but she was known as Bell to her family and friends. She first enters the criminal records at the age of eighteen.

I ordered the record and it came through very promptly from ScottishIndexes. Bell was arrested for drunkenness and interrupting passengers. In short, she was just the same then as she was in later years; alcohol made her vocal. She wasn’t afraid of attracting attention. She wasn’t afraid of conflict. And even then she had little hope for the future.

Edinburgh was a hard place to be vagrant. Bitterly cold, the inhabitants deeply suspicious, the wharf areas full of damp and decay. And utterly filled with desperation and depravity. A young girl in the midst of all this was at risk of all kinds of danger. She had to be tough just to stay alive.

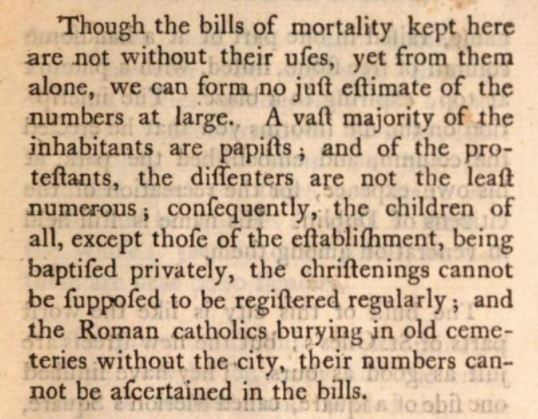

This is an excerpt about recommitments to Edinburgh Bridewell, the city’s main prison.

Bell spent 30 days in gaol, from 17th April to 17th May. After leaving prison she seems to have stayed in Edinburgh.

She’s put her age down slightly in this record; she was actually 19. The record also refers to a previous commitment on 22nd December 1822. She was seventeen then.

Every year from 1824 to 1828, there’s a record for Bell Anderson going into Edinburgh Bridewell for some short time. She was caught in the cycle of crime. And even then, it seems, alcohol had a hold on her. Maybe a physical hold, but certainly it was her escape, her way of relaxing. Her way of feeling human in a very harsh world.

The various incarcerations suggest she was drinking heavily and becoming very comfortable with gaol. The alcohol took hold with a vengeance. But at this stage drinking was a happy thing; something you did with your friends. They were all drinking as much as each other. There was camaraderie and solidarity. They were found family.

Somewhere around 1826 she met Robert Donaldson.

When Bell was twenty two years old, Robert was twenty eight. He was a tailor from Perthshire, black haired, brown eyed and tall. In 1828 he was lame in the left leg, there’s no indication if that was a recent injury or if he might have been born that way.

In her 1827 criminal record, Bell is surnamed Anderson. In 1828 she is Bell Robertson nee Anderson, and the two of them have a child, for whom I can find no baptism.

There’s no record of a marriage that I can find either. Maybe no ceremony was conducted, maybe the birth of the child was ceremony enough.

So contrary to the ‘single’ status we see in the South Australia records, by the end of 1828, at the age of twenty two years, Bell was a married woman and a mother.

A report of this court appearance was printed by various Scottish papers.

“In the case of William Paterson, Janet Morrison, Marion Campbell or Ross, Robert Donaldson and Isabella Anderson or Donaldson, accused of robbing of his watch a man who had been inveigled by some of the females to a house kept by Paterson – Campbell and Anderson were sentenced to be transported for 7 years – Paterson, Donaldson and Janet Morrison to be transported for fourteen years. The Lord Justice Clerk, in the course of his observation on this case, dwelt most strongly and most justly on the evil tendency of such houses as that kept by Paterson, but for which, crimes in this city would be much less frequent, and the property of the citizens much more secure.“

(Inverness Journal and Northern Advertiser 26 December 1828)

Reading between the lines, the house was the centre for an organised gang of criminals, maybe a brothel as well. It must have been exciting for a youngster like Bell. She possibly met the others in one of her first gaol stints. Her baby lived there too. Maybe was born there.

This time, incarceration tore Bell’s world apart.

The baby’s name was Joan and she was just seven months old at the time of sentencing. All we know about her comes from the ship’s medical log.

Back in gaol, Joan was forcibly weaned from her mother “in preparation for the journey.” It was probably intended that she should die. Babies did die during weaning, it happened in Van Diemen’s Land after arrival.

Joan lived. She was taken on board the ‘Lady of the Lake’ with her mother and the two other women.

It was a journey that shook even the surgeon. His notes are heartfelt. He tried to maintain health on board – but they were handicapped from the start.

There are some dire notes in the medical log for that voyage (11b).

“From 18-31 May 1829, we received 10 free women and 19 children; 81 female prisoners and 17 children, the largest ever sent to New South Wales in so small a vessel; and I may here observe, she was the smallest ship ever taken up to convey convicts. We were visited repeatedly by Mrs Pryoe and Miss Lydia Irving, the quakers, while at Woolwich, who appeared to be indefatigable in endeavouring to impress upon the prisoners the necessity of abandoning their evil ways, and becoming useful members of society. After several excellent admonitory discourses they distributed to them testaments, religious tracts, and several articles of comfort for their use during the voyage. “

Later in the journal:

“On 8 July 1829 we reached Teneriffe to replenish our water, and procure fresh provisions for the convicts. Anna Maria Dix an infant nineteen months old died (on the 30 July) of atrophy, arising in some respects from want of proper food, having been deprived of its milk diet on embarking at Woolwich. On the 16 October 1829 it blew a complete hurricane, when the ship was obliged to be hove to the wind. On 30 September 1829, Christiana McDonald, a convict, aged 18, fell overboard, in endeavouring to save her cap, which was blown into main channels. The ship was going through the water at the rate of eight knots at the time. The helm was instantly put down, and a boat lowered, but she sunk almost immediately. All prisoners were landed on 6 November 1829. I may here be permitted to observe that a ship of the small tonnage of the Lady of the Lake is by no means adapted to carry out female prisoners from being constantly wet between decks and the hatches being obliged to be put on, thereby causing great deterioration of the atmosphere in the prison.“

The surgeon wrote at great length about the patients in his care. The first was little Anna Maria Dix, mentioned above. But there were many others, including little Joan Donaldson.

Surgeon’s Report Joan Donaldson

“August 9th 1829. Joan Donaldson aged 12 months. “

“This infant was a puny weakly child when received on board – was weaned at seven months old preparatory to accompanying her mother Joan [sic] Donaldson alias Anderson, a convict. The change of diet from that of (cow’s) milk to oatmeal and rice made a very striking alteration in her appearance the first month after quitting England. In fact, she never relished either gruel or rice, and latterly refused the former altogether, but made use of ??? and biscuit powder however this was soon expended.“

“On the 9th August she was very much emaciated and debilitated.“

“Difficult dentition about this period ushered in a train of febrile symptoms, accompanied by great irritation and almost total loss of appetite.”

The surgeon describes how he treated little Joan with mild purges and tepid baths.

“3rd September 1829: Eruption made its appearance behind the ears, head and different parts of the body. She was also attacked by diarrhea, aggravated by the increased irritation.”

She was dosed with ‘Cretaceous mixture with the addition of Tincture of Cinnamon’, plus occasionally a “mild purge of calomel and rhubarb“.

“10th September 1829: The irritation was much abated, but she had become so reduced, and appetite having failed, that I entertained no hopes of her recovering. On the 10th September as 6.30pm she expired.“

Poor Bell.

What she really thought, we’ll never know, but she’d grown up so lonely, so unprotected that I suspect she cleaved very hard to that child. And now Joan was dead; killed by the meddling of the authorities who thought they knew better than she did.

Bell had the rest of the journey to dwell on her thoughts.

The ‘Lady of the Lake’ arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on 1st November 1829.

The three women were sisters in adversity. It was probably a mistake transporting them together, they were trouble from the day they arrived. Bell, Marion and Janet’s conduct reports look remarkably similar. Obscene language, drinking, not showing up for duty. Janet went off to some drinking establishment with her master’s child in tow. Bell was recalled from one position for disgusting language in front of the mistress’s children.

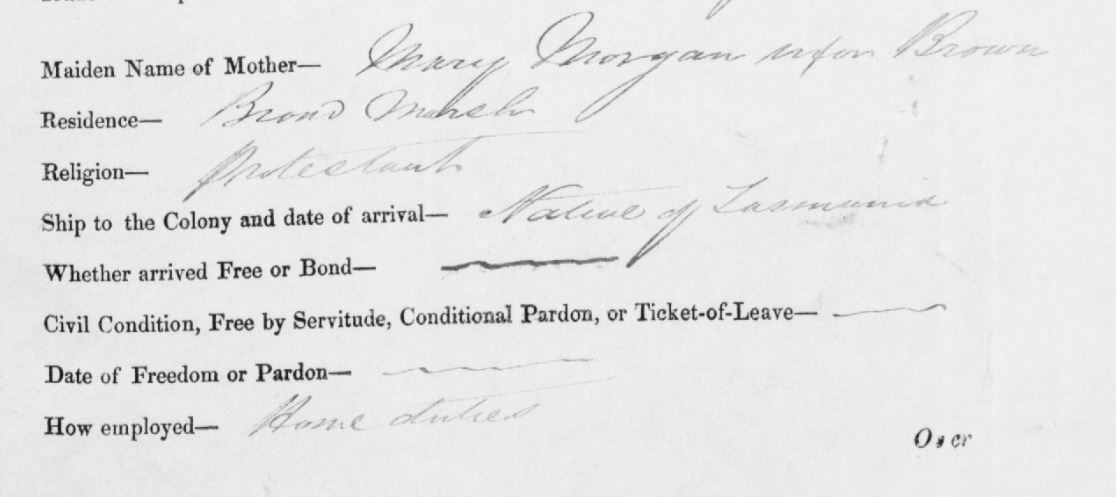

It’s probably too hard to read in this blog, but here is Bell’s conduct report. Full of detail. Full of strife.

The authorities had this strange idea that domestic service came naturally to a woman. There was a bit of training on the boat, but it was a big ask for girls who had run wild since childhood. It might have worked .. but Bell knew that authority figures couldn’t be trusted. She was tougher, stronger, in her own eyes far more resilient than a woman whose principal focus was getting bread to rise and putting a ribbon in the hair of a pampered child. A woman who had everything Bell had lost – how that was thrown in her face! Every day when she woke, she was in the midst of the world she’d thought she had.

From the vantage point of the educated future we know it wasn’t really like that. Bell was not in a good place. Her version of domesticity was full of danger and unhealthy living. She was about to raise that child in very risky conditions. But Bell wouldn’t have seen it that way, and Joan had died a needless death that nobody should have to die.

Plus, Bell was probably battling alcoholism before she even left Scotland, and in this land where wages were sometimes paid in ale, she had no hope of staying sober.

Here is Bell’s description:

A tiny woman with hazel eyes and dark hair, but larger than life like so many of those Scottish convict women. Volatile and restless, Bell owed nothing to anybody.

Her husband arrived the following year and his convict career was as active as hers. Plenty of drunkenness, absconding, petty thefts.

They never got back together. It seems as if they planned to at the start, each declared that their spouse was being transported too. But as the years went by, it just didn’t happen.

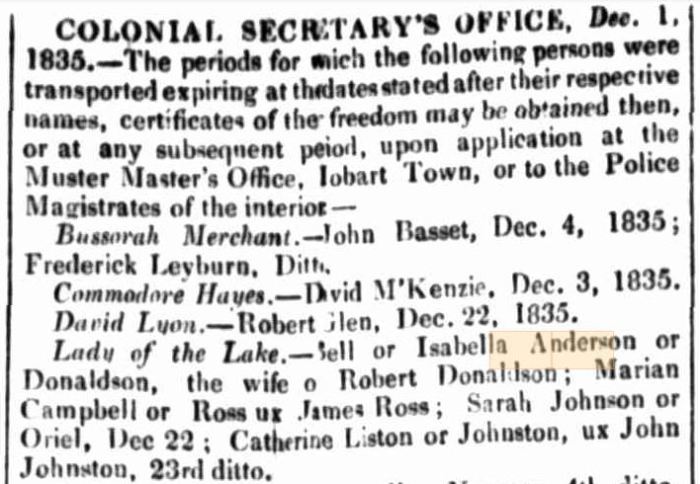

Bell and Marion’s time was up in 1835. (11)

The freedom was too much. Bell had never experienced normal life. I don’t know what her childhood was like, but given she was in prison by the age of seventeen, she’d found the wild side long before she knew anything of domesticity. Finally free in Van Diemen’s Land, she could only do what she had always done – drink. (12)

‘Glorious’ is an old word meaning ‘blissfully drunk’.

What was she to do? Bell was married. Her husband was inaccessible, but he was nearby and that meant she wasn’t free to hook up with someone else – at least, not very publicly, which meant a respectable man was unlikely to have anything to do with her.

Honestly, I don’t think Bell wanted a man in her life. She was independent. She had a sense of humour and people liked her. That’s why the two women came looking for her at the gaol that time. That’s why the journalist constantly wrote up her arrests. That’s why people discussed her possible death in those early years. She was a huge problem, but they didn’t hate her for it. They tried to help.

Bell lived in a world of prostitution and deception, but none of her difficulties involve men. She drank and got mouthy, that was all. But she drank alone, or she drank with other women. If there really were sexual encounter, they seem to have been purely business.

To me, it seems like she had a deep distrust of men. Any time a man showed interest she probably ran a mile from him.

She spent most of her convict years at Georgetown in the north. Maybe she went bush. Van Diemen’s Land was a small place in those days. If she’d stayed in Hobart or Launceston I think we’d see more of her in the police reports.

As for her friends, Janet was only halfway through her sentence, and Marion .. there’s a Marion Campbell (widow) who married convict Stephen Barnes in 1836, that might be her. Maybe. Those two lived very quietly as married servants in a household.

Bell went to South Australia in 1838, the year her husband was granted his ticket of leave.

Did she know he was getting that? Had they planned to go together, for Robert to abscond with here? Or was she leaving before he could gain his restricted freedom?

There’s no clear record of Bell’s journey to Adelaide. Various ships left from either Hobart or Launceston, some not listing passengers by name.

Perhaps the plan was for Bell to go first and set them up in Adelaide, and for Robert to follow when he was actually free. Or maybe he was ready to abscond, that certainly happened with ticket-of-leavers.

But he ended up arrested for drunkenness and you can’t get drunk when on a ticket of leave. His ticket of leave was revoked. Did Isabella wait in vain, thinking Robert had just abandoned her? Did she stay single for him until it was too late, until her health and her mind was gone?

Bell was already in Adelaide, using her maiden name and declaring herself a single woman.

Maybe it was Bell’s fresh start. She very firmly called herself single; even in the news reports she referred to herself as ‘Miss Anderson’. Was that irony? Was she remembering a husband and child whenever she said it?

All we know is how she lived through the next decade.

In the 1850s she settled down a little. Her health was very bad.

Let’s skip forward a few years to 1st March 1853 (13).

These are the last years that Isabella appears in court, so I’ll put them in. This is 21st March 1854 (14)

And two days later on 23rd March 1854 (15)

It was the final charge for Isabella Anderson, and I expect she was probably glad of it. She spent a short time in gaol and on 4th May 1854 she was taken to the lunatic asylum.

Here’s a truncated version of that last gaol record:

There’s nothing else in the papers about Bell Anderson until 1860. She gets a brief mention in a report on the asylum. It’s an indication of the level of her notoriety nearly a decade before.

23rd Jan 1860 (16)

Bell passed away in the Lunatic Asylum on 27th April 1866, aged 52 years, although not even Bell probably remembered her actual age. She was buried in West Terrace Cemetery in Adelaide and has an entry on FindAGrave, but the grave has been reclaimed for another person now.

No trace of Bell remains. I’ve managed to trace one of her sisters, Elizabeth Bruce Anderson, who married James Weir and emigrated to Canada. Elizabeth wasn’t as wild, it seems. Maybe she breathed a sigh of relief when she lost sight of her troubled little sister.

It’s possible that after her first gaol term Bell was ashamed to go home, or maybe she was banned from returning. Whatever the story, it’s a shame that Bell never did find a place where she felt she belonged. But hopefully the last few years were ones of peace.

Without meaning it, Bell has earned herself a place in the history books as one of the best chronicled colonists of South Australia. I like to think she’d find that funny too.

Bell Anderson alternatives in current research:

There are two

- A baby Elizabeth Philips was baptised in Launceston Tasmania on 30 Jun 1837, parents Henry Philips and Isabella Anderson. This Isabella was likely to be Isabella Henderson of the ship Mellish whose marriage application to Henry Phillips was approved that same year.

- Isabella Donaldson aged 64 died in Hobart in 1863, wife of a carpenter. I think that Isabella was the wife of William Donaldson, carpenter. Her death notice was in the paper that year. William Donaldson married Isabella Trotter in Dunino, Fife, Scotland and they had one son, Benjamin Trotter Donaldson. William Donaldson, carpenter, died on 20 Jun 1883 in the Tasmanian Huon, his death informed by his son Benjamin.

References

(1a) “Australia, South Australia, Prison Records, 1838-1912.” Database. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 10 February 2021. Citing Attorney General Office of South Australia, Adelaide.

(1b) “Australia, South Australia, Prison Records, 1838-1912.” Database. FamilySearch. https://FamilySearch.org : 10 February 2021. Citing Attorney General Office of South Australia, Adelaide.

(1c) (1842, April 12). Southern Australian (Adelaide, SA : 1838 – 1844), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page6245883

(2) AGRICULTURAL AND HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY. (1844, May 1). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 2. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27447055

(3) POLICE COMMISSIONER’S COURT. (1845, January 1). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27448889

(4) (1845, May 2). South Australian (Adelaide, SA : 1844 – 1851), p. 2. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71601339

(5) POLICE COMMISSIONER’S COURT. (1845, May 17). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27450146

(6) POLICE COMMISSIONER’S COURT. (1845, May 21). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27450186

(7) Friday, 24th April, (1846, April 25). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 – 1904), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158922328

(8) POLICE COMMISSIONER’S COURT. (1845, August 23). South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register (Adelaide, SA : 1845 – 1847), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article195933068

(9) APA citationThursday, 9th March. (1848, March 11). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48727398

(10) Friday, 26th May. (1848, May 27). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48729070

(11) FROM THE HOBART TOWN GAZETTE. Friday, Dec. 4, 1835. (1835, December 10). Launceston Advertiser (Tas. : 1829 – 1846), p. 4. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article84776811

(11b) National Archives of London ADM 101/41/9

(12) LAUNCESTON POLICE INTELLIGENCE. (1836, January 16). The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 – 1880), p. 2. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65951338

(13) POLICE COURT. (1853, March 3). Adelaide Times (SA : 1848 – 1858), p. 3. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207010884

(14) WILLUNGA DISTRICT COUNCIL. (1854, March 21). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48554144

(15) SOUTHERN RACES. (1854, March 23). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved January 26, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48553886