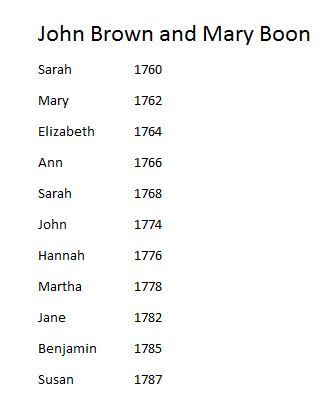

Another relative has agreed to take a DNA test for me, so I’m updating a branch of the tree that I haven’t looked at for a while. In doing so, I reconnected with Kate Fitzgerald and her plight struck me all over again. She deserves a blog post.

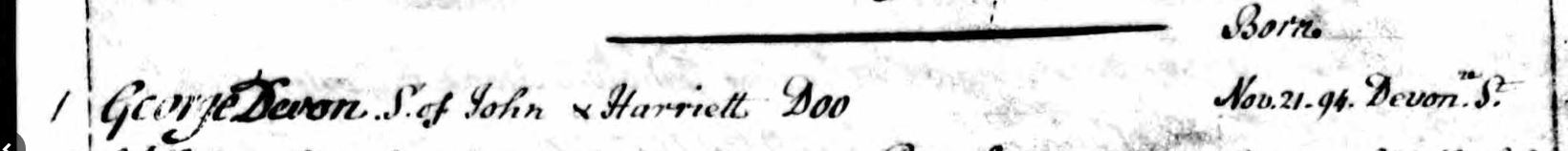

Her full name was Isabella Kate Johnston Fitzgerald, but she was always known as ‘Kate’. She was – according to a later note – born in Trinidad on the property of her Uncle Andrew Johnston who had a plantation. Her father was Robert Appleyard Fitzgerald, a self-centred Irishman of good family, keen to improve the family fortunes and create his own empire.

Not that his family fortunes were bad – he was born at Geraldine House in Limerick, the son of a silversmith of decent income who had married a wealthy woman. But the family lived in the shadow of former glory – a grandchild, it seems, of one of the Dukes of Leinster. Possibly by an illegitimate liaison, it’s hard to know. The point here is that Robert Appleyard Fitzgerald possessed a strong belief that he was born to greatness and all he had to do was make the right decisions and everything would fall into place.

He made a good start by marrying Isabella Forrester Johnston, daughter of Henry Johnston and Henrietta Ogilvie. They moved out to Trinidad, the plan being that Robert would purchase a plantation and make his fortune.

Yes, they undoubtedly had slaves. There are very few details about this location. Robert and his wife Isabella were, from all we know, very happy.

Kate’s little sister was born on 1st January 1826, also in Trinidad. But the family wasn’t settled.

That is, Robert wasn’t settled. Always with an eye to the next great thing, Robert was inspired by the Americas and the gains that could be made there.

They moved to Woodbridge, New Jersey. We know this from the births of two sons, William Henry Fitzgerald in early 1830, and little Robert Appleyard on 8th August 1832.

Sickness struck the family here. Little William died of cholera on the 17th August. It might even have been brought to the household by the doctor attending the baby’s birth.

The baby lived two weeks. He took his last breath on 28th August 1832 and was buried the following day. Cholera was given as cause of death.

After the baby’s death they made another move. By the end of that year the family was in New Orleans.

They were just in time for the Black Cholera outbreak of 1833.

There’s no indication of Kate and Ellen’s presence in New Orleans – or even in New Jersey for that matter. Possibly because of their mother’s health after the death of little Robert, they were sent back to England with Uncle Andrew.

It was, as events show, a decision that saved their life, but I’d like to point out that this might not have been the reason the family was separated. Robert was like this. He was not an evil man, he cared very much for the people around him. But he was entirely without empathy and at the heart of everything he did was himself. A true narcissist, not malevolent at all, very generous and pleased with himself for being so, but with no concept that what suited him might not be best for anyone else.

If he was truly concerned for his family, he’d have sent his wife as well.

The girls were quite possibly sent to England just because it was easier to travel without them. And because Isabella could be an engaged social partner if she wasn’t overburdened with family.

Here’s a quote from an academic article about the 1833 epidemic.

Local merchants tried unsuccessfully to calm panic by suppressing information. Cholera was not good for business. Business was depressed. Organized religion thrived. National and state days of prayer were appointed to appease an angry God.

During these frightening times, the people learned nothing about the infectiousness of cholera or about its prevention through sanitation. Their experiences tended to reinforce their belief in miasmas or divine retribution.

(3)

I think that explains the situation very nicely.

I found a wonderful snippet in the Boston Morning Post on 29th May 1833.

extract of a letter dated ‘Mobile, May 8’

“On my way to this place from New Orleans, I put up at a hotel near the Landing below the town. A Mr Fitzgerald, formerly a merchant of New York, but now of New Orleans, slept with his lady in a chamber next to mine. The next morning I heard him tell Mr B, a gentlement who accompanied me, on the piazza, that his wife had been sick all night with retching and cramps. I at once suspected cholera, and got out of bed to offer my services, but was told a physician had been sent for and would be there immediately. My suspicion proved correct, and she died in a few hours. The husband appeared very disconsolate. He has buried four children, two here, by cholera last summer, and has two living in England.”

For a random newspaper correspondence it’s remarkably accurate. I’m not aware of two more children dying elsewhere but there is time in their marriage for it to occur, so maybe that is true also.

I haven’t found an exact registration for Isabella’s death or burial, but this article matches dates in the family tree drawn up by Isabella’s grandchild fifty years later.

Back in England, Kate and Ellen must have been informed of their mother’s death. And eventually – for short spells only – their father joined them, and took them out to his parents at Geraldine House in Rathkeale, Limerick.

Their father wasted no time finding a new mother for his daughters. With his suave confidence and good looks, his stories of travelling the world, his incessant but skillful namedropping and no doubt sophisticated social skills, he presented himself as a real catch. And it’s true, he came from a good family, there was money behind him. And he had all the mystique of past tragedy into the bargain.

The lucky woman was another Isabella and she was twenty years younger than he.

Isabella Stevenson was British. Born in 1814 to a family of good name but diminishing finances, she was just ten years older than Kate, twelve years older than Ellen. Her journals and letters show her to be a very kindhearted girl, quite sensitive, but one who had never experienced true hardship or tragedy. There was no sorrow in her but the sadness she felt for others. And being very deeply in love with her mesmerising husband, she took his opinon on everything as her own.

How the girls felt upon meeting her can only be guessed. Kate and Ellen were barely out of mourning.

The marriage was a lavish affair on 6th May 1835 and the whole family moved into premises in Dublin.

Two children were born to Robert and his second wife while here. Caroline in 1836 and a baby boy who died in his first day of life in 1837.

Robert was as restless as ever. After the death of their son they went back to New York. They were living here when little Frances was born in 1838. But like all of Robert’s business ventures, they ended up in trouble and returned to Ireland where the family could help them out.

At the age of fifteen, Robert felt it was time that Kate blossomed into full adulthood. A good marriage, that was clearly his thought, to the most useful son in law he could find.

Kate was launched on society. She hated it. It was not a success.

This takes us to 1840.

Kate was fifteen at the start of 1840. Her stepmother’s letters describe her as a solemn girl who rarely showed any emotion and rarely said a word. Taciturn, some said. But it’s clear that she spoke to Ellen and to her father at times. It’s clear that she and her stepmother never found common ground. Kate’s inability to communicate and Isabella’s inability to comprehend the effects of grief were insuperable barriers. The two were civil, but that was all.

Kate wasn’t really alone: she and Ellen were inseparable. The two had suffered together and had come through together. She could talk to Ellen. And Ellen didn’t really need words anyway, Ellen understood everything about her sister. Could speak for her at social functions, at the table. In return, Kate was a pillar of support for Ellen, took on the role of mother so completely that Ellen overcame the shock of their loss.

By now Robert was feeling the pinch again, his finances in poor order. He couldn’t throw a dowry behind her, not the way that would secure her a husband no matter what.

He turned his attention back to the world at large. Listened to stories about the antipodes, about the great need for educated men in senior administrative positions in the colonies. In Australia.

The girls were not part of this decision, but they seem to have coped with everything while they were together. So the plan was made; the two of them, their father, their sociable, cheerful and once-more-pregnant young stepmother and their little sisters (aged five and three) were to leave everything they knew and go out on an adventure.

Unlike the bounty immigrants and convict families, they were not leaving home forever. That was never the plan. They’d be back. But it still meant leaving everything they held dear. It would be an absence of some years.

Isabella’s day book gives a few details.

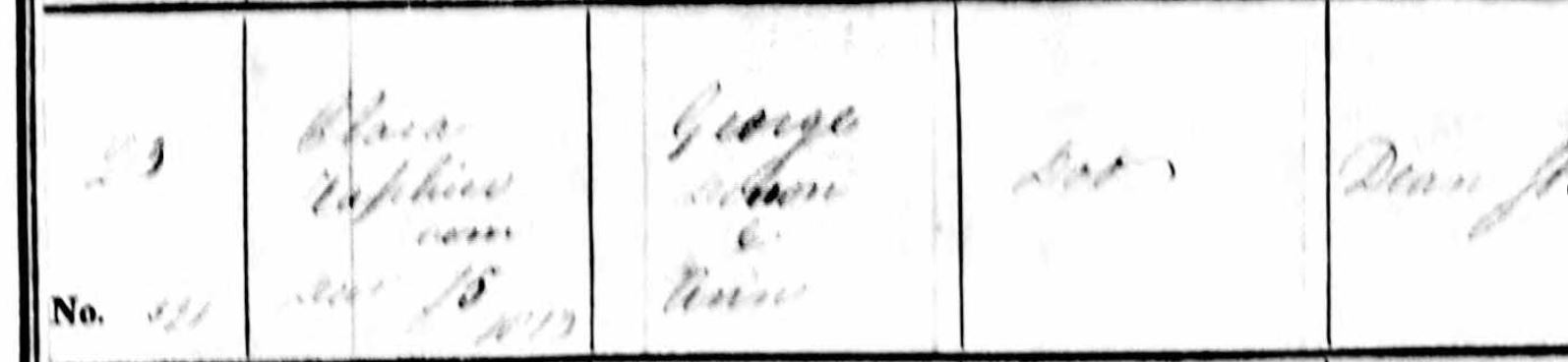

They went by ferry from Dublin to Hennor House in Hertfordshire, Isabella’s childhood home where her widowed mother and her brother still lived. Isabella was about seven months pregnant.

Kate turned sixteen on 24th June 1840, around the time of this journey.

In London they stayed with Constance. I’m a bit confused about that since Constance was a single woman at the time. I’m thinking they were actually all with their Aunt Frances Middleton, wife to Lambert Middleton who certainly had a town house. But I’m not quite sure. Isabella was very close to ‘Aunt Middleton’ and many of the surviving letters are correspondence between the two.

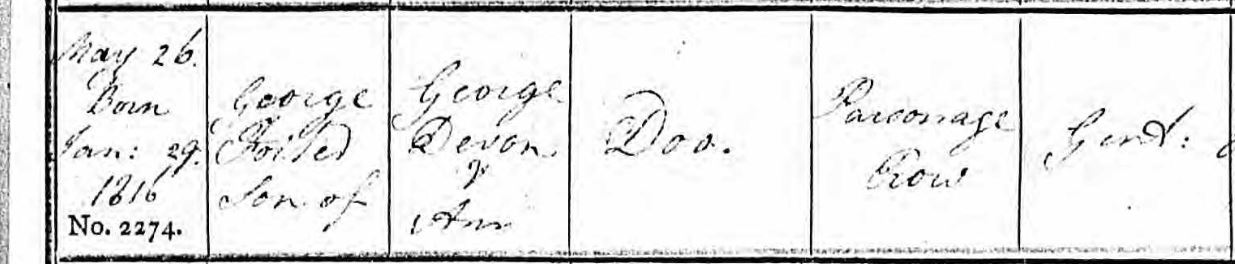

Kate’s new baby sister was born on 8th August 1840, mere days after their arrival. She was baptised Constance Dundas Fitzgerald in London. And on the 7th of September they were on board the ship Alfred.

The voyage was against the advice of Isabella’s brother-in-law doctor , and her mother, it seems, said some almost-harsh things about Robert and his lack of responsibility in putting a newly confined woman through such an arduous journey.

Through her months on the boat Isabella pointedly includes any meagre evidence she can find to ‘assuage’ her mother’s fears on that matter.

I know this post is about Kate, but Isabella’s journal gives some very telling details.

Keep in mind that she wrote the journal with a view to mailing it back to England for family to read, in lieu of letters. So she’s phrasing things carefully.

7th Sept 1840 Much engaged during the day in arranging state rooms, and securing trunks, boxes, books etc secure in their places. The sea smooth, a light fair wind, lovely evening, a glorious sunset, closed this first day of our long, long voyage and retired to bed at 9 o’clock fatigued in mind as well as body …

Journal of Isabella Fitzgerald nee Stevenson

She describes their embarkation in greater detail later, but I’d like to point out that this woman gave birth to her fourth child just four weeks earlier and she’s also caring for the other two, while tackling these settling in tasks. No wonder she’s fatigued! She does have two servants to help, but they are a pair of Irish girls working for their passage who have never acted in that capacity before, and the whole voyage is a matter of training them in the duties she needs them for, so she is actually doing most of the care herself.

It shows the family dynamics. She’s in a weakened physical state, she’s basically cabin bound, her husband is off hobnobbing with the Captain and other guests. And nobody is spending much time with Kate and Ellen. Not that they need it. They’re very self sufficient. And they have each other.

I wish to reinforce that fact. They have each other.

From Isabella’s diary.

I’ve skipped a lot of fascinating events in an attempt to keep it focused on Kate:

8th Sept Our meal hours are, B/fast 8; Luncheon 12; Dinner 3; Tea 6 and Supper 9 o’c. My seat at table is next to the Captain at his right hand; next to me, Robert /of course/; and then Ellen, close to her cabin door, Kate opposite to me between Mr Brett, first mate, and Mr Massy, a young Irish man, acquainted with the Limerick folks; Kate’s remarks as usual – few and far between!

12th Sept No incident worth recording, except a severe fall of a poor woman by which she fractured her skull, bled, blistered on the head and cupped on the neck. Robert assisted the Doctor. Another woman in the hospital with slight fever – great attention paid to cleanliness and fumigation to prevent disease; our Doctor – very gentlemanlike, intelligent, active and decided – keeps the people in good order.

18th Sept. Fresh breezes and squalls going our course towards Madeira, which we expect to make tomorrow; opened the piano and found the sound much deadened by the case, the ocean up to this time has rolled too much to attempt it; it is with difficulty we keep our seats at table, all holding on by our neighbours!

21st Sept To bear the heat; Kate and Ellen play and sing, occasionally, but the Piano being in the public Cabin or Cuddy, they cannot with any pleasure to themselves practice regularly. People continue healthy, only two in the hospital, the woman with the fractured skull and the woman with slight fever before mentioned, both mending slowly; several children have whooping cough.

28th Sept On Sunday night a heavy fall of rain with tropical lightning, such as is never seen in England, but no thunder; on its departure it took from us our lovely “trader” [wind] and we are now quietly moving with that lazy motion, so very undecided, that we are apprehensive of a calm, a calamity indeed, to our crowded ship, and without a breeze to give a circulation of air between decks we cannot expect to be entirely exempt from the visitation of fever, which but too often afflicts Emigrants in this Torrid Zone and frequently carries off numbers.

29th Sept Since Sunday the heat has been oppressive. The thermometer varying from 80 to 84. The hot winds from the coast of Africa are blowing upon us, making us all weak and languid. We sleep with our Cabin windows all open, have all left off our night caps, not excepting little Con, who suffers from the heat as much as any of us; she only wears the day caps when she goes on deck. Kate and Ellen /wonderful to tell/ have left off two garments; Carry and Fanny trot about in their frocks and “first things” only and no socks; the Doctor’s children the same. They are terribly burnt, so are we all, as we sit writing and reading on deck, without our bonnets but there is an awning put up every day.

30th Sept Kate and Ellen spend most of their time on Deck, working or reading, they also have regular lessons from Robert, in geography; and Robert often reads to us, while working. This plan tho’ has been a little broken in upon by the heat.

Oct 12th Lat 4.34 Lon 23.53 . Thermometer 80 by which it appears that we have only made 200 miles southing, during the last eight days, this is rather melancholy, still, we ought not to repine, but rather be thankful that we are all still preserved from sickness. The people [284 bounty emigrants in steerage] are lively and as happy as circumstances will permit, the poor creatures having many troubles and deprivations which they bear remarkably well, their greatest being the want of good water, a thing which time only can remedy by self-purification; it is really most loathsome and affects for tea so much that sometimes we can scarcely drink it. It is fortunate for us that we brought a filter, what we should have done without it, I know not; we are limited in the quantity of washing and drinking water, but with a little care find it quite sufficient. We have a good luxury, … a shower bath in our greater gallery or closet .. however, I have not partaken ; it has lately been put in order and Kate, Ellen and Robert take one almost daily before breakfast.

Nov 28th Our good fortune continues and we are making rapid progress but the vessel rolls terrifically at times, so much so that we have been obliged to have stanchions put up in our cabins by which to hold on, before which, we could not keep our seats, but were continually sliding up or down the window seat and lockers tumbling one over the other and I have adopted an excellent plan of securing myself when Baby is in my arms by tying myself to one of the posts by a rope around my waist! It is quite amusing to see Carry and Fanny balancing themselves with the motion of the vessel; when a heavy roll comes they lie down on the floor until it is over! You can easily imagine what uneasy, restless nights we often pass, with the exception of Kate, Ellen and Baby! All of whom sleep sounder the greater the motion! The rolling I spoke of in my letters from the Cape was nothing compared to what we have suffered from since we left it and it is only on a quiet day now and then that I can proceed with my journal, besides which it has now become cold, and our cuddy looks comfortless enough without fire and carpet.

Dec 8th 1840 The appearance of Cape Town from the bay is not very striking, being situated in a hollow at the entrance of a valley and the best part of it being hid by the termination of a hill, still, several good houses could be discerned thro’ the telescope, all being painted white and green, many of them having flat roofs; also two churches with spires, the one Lutheran and the other belonging to the Church of England. The scenery is magnificent, the Table Mountain, 3500 feet high, overhangs the town, rising almost perpendiculously at its back, its sides being flanked with beautiful hills, with immense ranges of rock of great height in the distance. …

On Saturday we went on shore escorted by Mr Bennet and Mr Massey, the town contains two or three handsome buildings, with a valuable library, and fine reading room, but the place was too Englified …

I took dear little Carry with me, who was much amused with the children, and talked much of being at the “Cape of Good Hope”, laying such stress on each word. The sensation of walking on solid ground was delightful at first, but the sun was very powerful, and we soon got tired, having been long without exercise, and I glad enough to get back on board again where I had more enjoyment from the recollection of my visit to Cape Town, than I had whilst there, particularly as dear Robert was not with me, whom I reluctantly spared to accompany Captain Crawford in a gig to “Constantia” about 12 miles from the town, where there is a vineyard producing about 5000 gallons of dark, sweet wine …

Dec 26th 1840 On Christmas Day the emigrants were treated with a dinner of fresh meat, plum pudding and wine; our treat was to be startled out of our sleep at 12 o’c on Christmas eve by the Band, playing in the cuddy and the Captain wishing us the compliments of the season thro’ his speaking trumpet! Our latitude was 45 deg 9 mins East Lon 95 deg 37 mins – bringing us within a few days sail of the South Western point of Australia; being the Swan River settlement. Thus our Christmas Day was passed at sea, contrary to the expectations of many of us, who had hoped to partake of Christmas fare with there friends, but for ourselves, who have no one to welcome us, or make merry with at the new home to which we are going, we did not regret it.

Jan 1st 1841 New years Day was ushered in by music at midnight, and a similar ceremony gone through that took place on Christmas eve. It being Ellen’s birthday, it was the Captain’s wish to have a sort of fete in compliment to her, but Robert requested that he would not notice it, as it might give opportunities for freedoms which we should wish to avoid; her health was however proposed by the Doctor, and drank in champagne. [NOTE: Ellen turned fifteen]

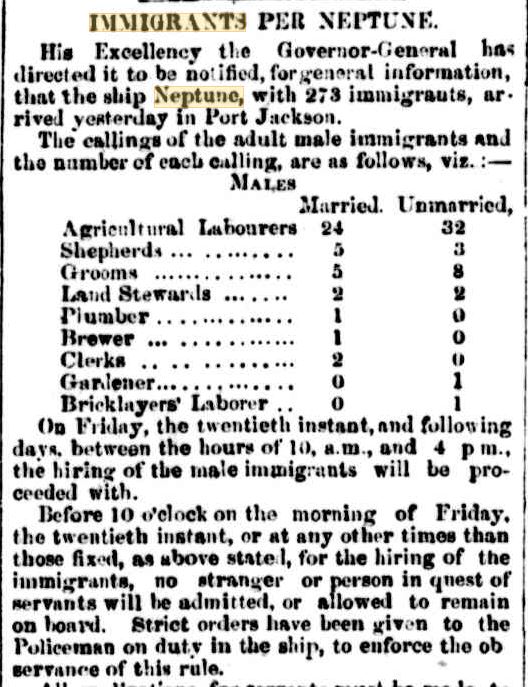

Jan 18th 1841 (Sydney) The anchor is dropped and we are once more quiet so far as the motion of the vessel is concerned; the harbour is extremely beautiful, appearing like a large lake enclosed with wooded hills and we have a peep of the town at a little distance; the vessel will be hauled up to Walker’s wharf in a few days. 6 o’clock. Robert and a few of the gentlemen have been ashore looking for quarters, which by all accounts are very difficult to be procured, and rents exhorbitant, which news does not tend to raise our spirits; lodgings of some description must be got immediately as it is expected that we leave the vessel in 48 hours from the time of arrival; the heat coming so suddenly upon us is almost overpowering.

A letter from Isabella to her mother the following day (19th Jan 1841).

My dear, dear Mother,

After hard work we have left the Alfred and got into lodging for which, we must pay 4 pounds per week, and we are considered exceedingly fortunate in getting them, even at that price. Robert has seen the Governor and the Colonial Secretary and has been received in the most flattering manner. May God grant him success. We are only this moment got in. I have much to do before night. Farewell dear Mamma.

The end of a long and difficult journey, but Isabella’s version was that of a cabin bound mother. Out on deck, things were different. For Kate, they were simultaneously better and worse.

The cabin passengers became quite well acquainted on this journey. They came from similar backgrounds, and among them were some of more impressive families than the Fitzgeralds, including Alexander and Thomas Crawford, Superintendent Cartwright and his family, a Mr John Bennet, Miss Harnett, and brothers John and Rawdon McDouall.

John Crichton Stuart McDouall was twenty one at the time of this voyage, his brother Rawdon was nineteen. They struck up a friendship with the Fitzgeralds.

To be more precise, John McDouall and Ellen Fitzgerald struck up a friendship, with the blessing of Ellen’s father who for whatever reason failed to say a thing about it to his wife.

Things came to a head upon their arrival in Sydney. Here is another letter from Isabella to her mother.

28th January 1841

My dearest Mother,

Having settled ourselves so far as to be able to turn around and look about us, my objective is to give you, in whose thoughts and fond solicitude I know I have so large a share, some account of our proceedings and prospects. The latter, judging by the very friendly receptions my dear Robert has met with, are promising, and I thank God. He who has so mercifully upheld us through so many trials and difficulties, and raised up a friend to help us, from whom Robert has borrowed money, but He only knows when we may be enabled to repay it. Business now is greatly depressed, and two or three large houses have failed; everywhere there is the same tale of distress; farms are given up and sold at a sacrifice; cattle can be purchased at 3 Pound a head, sheep 5 shillings and lambs into the bargain, any person having money here now could double it in twelve months, but alas we have it not. From all we have yet heard, it seems most likely that New Zealand will yet be our destination; there is nothing to be got here but a Police Magistracy with from 250-300 Pounds a year, all other situations being and to fill which we should be obliged to go three or four hundred miles up in the country, entirely cut off from society and without any prospect of advancement, whereas in New Zealand some of the best appointments are yet to be made and Government has been on the lookout for persons competent to fill them. Six months ago he could have got the best appointment the country affords, that of Colonial Secretary, still, from Robert’s knowledge of business and his having held the above named situation in the West Indies, I have every confidence he will yet get a good one. He will have another interview with the Governor on Saturday; he has seen the Attorney General and Postmaster-General and will soon have delivered all his letters …

And another letter to follow:

10th February 1841

All that we have heard is in favour of going to New Zealand, which we have finally decided. We go to Auckland on the ‘River Thames’, on the eastern coast of the northern Island .. carrying letters from the British government to the Governor Captain Hobbs, one of which is from Lieutenant John Russell which is considered as good as an appointment.

I go to encounter great inconveniences doubtless, and probably hardships situated as we are without means, still having firm confidence in Him who has so mercifully supported us thus far.

But I must hasten to communicate what, tho’ left to the last is the most important news I have to tell .. it is this: Ellen is going to be married. To a gentleman who came out with us of very good family and independent means, the son of a Clergyman, who is a Prebendary of the Cathedral of Peterboro .. and he is first cousin to the Marquis of Bute. But I am happy to say that his high connection is not his only recommendation; though very young, only 23 years, he appears very steady, sensible and intelligent, his manners quiet but pleasing and has been accustomed to female society having several sisters; altogether. He was a favourite with us long before we suspected anything, which was not until a week or two before we landed, thou’ I believe they have pretty well understood each other from the time we left the Cape. They are to be married on Tuesday the 23rd. When matters were first arranged we had no idea of it taking place for a few months, which would have given Mr McDouall an opportunity of purchasing an estate in the country, but when we finally decided to go [to New Zealand] without loss of time the gentleman did not much relish the idea of his intended bride being taken away from him, so Robert proposed our waiting a fortnight in order that the marriage might take place.

Kate is to remain with them on a visit for three or four months, thus our expenses down to New Zealand will be much lightened ..

It was the best arrangement for Kate, in a circumstance that couldn’t have been easy. A few months to ease the parting blow, to step back from that formerly inseparable companion and allow a stranger to move right into her place. However kind Ellen might be, it was going to be tough. However generous Kate was, however much she wanted Ellen’s happiness, it was going to be sad in some ways. But at least she was still valued for herself here .. not just an additional expense ..

The next details also come via Isabella, from her day book this time. (Ellen married to John McDouall at Sydney. Accompanied by Kate to Parramatta.)

(Sailed from Sydney for New Zealand.)

In the end Kate spent several months with her sister. Long enough for a lot of letters to pass between family members in England, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand, many of them written on scraps of paper with densely crossed lines. Robert had secured a position as Registrar of the Supreme Court and Manager of Intestate Estates. Jobs for a general clerk, and in a brand new colony, how many Intestate Estates were there likely to be? But they were desperate by then, and in debt. And the society was high.

Kate knew little of that, just the optimistic letters sent by her father and stepmother. In the surviving records the only letter came from her father and was addressed not to his daughters but to Ellen’s husband ‘Mac’. Paper was very scarce. In this letter he asks his son in law to pass on a message to Kate.

Perhaps she had her own and it has been lost in time.

On the surface, all was fine. She stayed in Parramatta with her sister and brother in law, and others of his family. And when John purchased his rural property at New Freugh, she boarded a ship for New Zealand and went off to her new home. Back to her father.

She was on her own for the first time and still very young, still a girl who scarcely spoke, who gave no hint of her feelings. No doubt missing her sister. It must have struck her that she was finally, truly, alone.

She just after Christmas and must have missed Ellen’s sixteenth birthday by a matter of days.

They met her with warmth, according to Isabella. And introduced her to their new friends. To Governor Hobson and his wife who had become a good friend to Isabella, and to Colonial Secretary Willoughby Shortland who had come out with Hobson and was – like Robert Appleyard Fitzgerald – angling for a decent promotion. Robert’s competition, but far better connected, the heir to a large estate in Devon. A man from a good school who was not only educated, but understood social nuance in a way that Robert did not.

When Kate first met Willoughby Shortland he was thirty seven years old. Kate was seventeen.

There used to be a lot more data out there about Willoughby. And much speculation. Online trees link him to a Maori woman with whom he may have had three children. I have no idea what facts support this, if any. But I shall place those details here in the hopes that someone who reads this can confirm or repute.

So, Willoughby’s official background:

He served on Jamaica Station from 1829–33 where he was associated with Captain William Hobson, and where he attained his first command, HMS Monkey, in 1830. He was invalided home in 1833, but six years later accompanied Hobson to Sydney, where he was appointed to New Zealand as Police Magistrate. Shortland became New Zealand Colonial Secretary on 3 May 1841 and on Hobson’s death (10 September 1842) succeeded him as Administrator pending Governor FitzRoy’s arrival 15 months later.

An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/shortland-commander-willoughby-rn

And the New Zealand oral history that is believed to refer to him:

Mordechai was of Jewish descent. Te Ruki Kawiti wed him to his only daughter to lift the Tapu of the Puhi that he had put on her. After they had three children two of which were twins (Hoterene and Riria) the people of the Rohe told Kawiti that Mordechai had to leave so that Tuwahinenui – (Kawiti’s Daughter) could be tomo to Ruatara (One of Kawati’s main warriors). Upset by this, Mordechai left for Australia with his two sons Hohaia and Hoterene. Whilst gone Riria fretted for her twin and her health took a turn for the worst. Kawiti sent people to search for him and to ask for Hoterene to be brought back to save the life of his sister. They found them and Hoterene was brought home to his sisters side. Her health returned, however nothing was heard of Mordechai after this. It is uncertain as to weather he remained in Australia or returned to Israel.

https://www.geni.com/people/Lt-Willoughby-Shortland/6000000009076741667 (Yes, not a very credible source. But there are a variety of sources listed there that are no longer accessible, so it can’t be discounted yet.)

And another oral history:

When Lt. Willoughby Shortland in his role as Colonial Secretary took the Treaty of Waitangi to Tuahine’s father Te Ruki Kawiti after all else had signed in the north, Kawiti told him that the cost of his signature was Willoughby’s name. Willoughby married Tuahine, Te Ruki’s daughter and fathered birth to twins who carried his Shortland name. Te Ruki took Shortland, translated it into “Hoterene” and gave it to Tuahine’s son, who then became known as Hoterene. All Shortland lines of descent in Ngati-Hine come from him.

It’s true that there are Maori people with the surname Shortland. Willoughby’s brother Edward had a strong interest in the Maori language and lived with a tribe for some time. But the three abovementioned children were born around 1833 to 1840, before Edward arrived in the country.

Anyway, it gives a clue as to the Shortland involvement in local affairs.

Why is this relevant?

Because on the 8th of January 1842, one week after he first met Kate, Willoughby Shortland proposed to her.

Kate said no.

And that is the event that prompted me to write this post.

Poor Kate. She’s lost her sister, the only one who truly cared for her. She has no mother but overworked Isabella who sees the proposal as an ideal solution to the Problem of the Difficult Stepdaughter. It’s perfect for Robert who knows he’s not going to get a promotion without better family contacts.

I think it was set up between Robert and Willoughby. I think someone was pushing Willoughby to shake off his Maori connections, and whatever other sordid entanglements he’d formed. And Robert always saw his daughters as magnets for useful sons in law. I think the second she disembarked from that boat her father was deciding how to bring her thoughts round to a marriage. And Willoughby sized her up the second he met her, knowing he already had her father’s approval. And probably the approval of William Hobson and his wife who was Isabella’s friend.

In a letter to her Aunt Middleton, Isabella mentioned the fuss. How astounded they all were at Kate’s obstinacy, how embarrassed they were. How Robert had had several long discussions with her and how strange it was that Kate couldn’t see what a wonderful opportunity was before her, especially when she’d just spent time with Ellen and could see the advantages of a good marriage.

I feel so, so sorry for Kate.

Yes, she did know the advantages of a good marriage.

Ellen’s was a fairytale romance, swept off her feet by a young man who adored her. A linking of like minds, two equals with great respect for each other. And that comes through larger than life. John McDouall treated his wife with complete respect. In his letters he acknowledges her opinion. Her likes and dislikes. It’s clear they discuss matters and form mutual agreements.

And here’s Willoughby – formal, somewhat arrogant, seeing her as a way out of a difficulty. I mean, it’s possible that he fell in love with her. But if he did and she then said no, would he have pursued the matter further?

It’s hard to know what’s in someone’s head. But I don’t think that was it. Especially looking at later years. And whatever his feelings, Kate said no!

But her family were so blinded by the brilliance of the marriage that they didn’t care.

A lot of my ancestors were in arranged marriages. It can work. I don’t personally have a problem with it. Only with this one because poor Kate said no. But she had no friends to take her side. And she was just seventeen and her mother was dead and her sister was an ocean away.

In the end, Kate said yes.

A superseded version of the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (1966) says the following about Willougby. Note there’s some bias here. But I particularly wanted to show that this opinion is out there.

In office, Shortland by his pomposity, flamboyancy of character, and lack of tact, quickly made himself obnoxious to the colonists, while his abruptness in dissolving the Port Nicholson Settlers’ Council aroused resentment throughout the New Zealand Company’s settlements. His abysmal ignorance of financial matters, and his recourse to the questionable expedient of issuing unauthorised drafts on the Imperial Treasury, added considerably to the colony’s public debt. Governor FitzRoy chose to blame all the shortcomings he found in the New Zealand Administration upon Shortland, whom he accordingly dismissed from office on 31 December 1843.

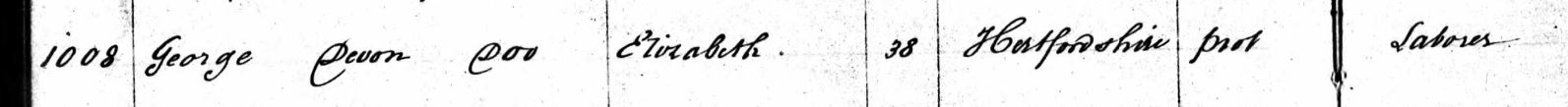

The Colonial Office did not share FitzRoy’s view in this matter, and considered his dispatches were at the least satisfactory, factual, and to the point. Accordingly he was appointed President of Nevis in 1845, and Governor of Tobago (1854–56). He retired from the Navy with the rank of Commander on 1 July 1864, and thereafter lived on his family property, Courtlands, Devonshire, until his death on 7 October 1869.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/shortland-commander-willoughby-rn

I don’t think Willoughby was a bad person. To me, he seems to be another troubled man whose family were determined to rule his life. Not an individual, pushed into a career path that didn’t suit him. Somewhat entitled, perhaps. It’s hard to look behind the official facade. Maybe he didn’t want to get married either.

Maybe he and Kate actually had that in common. And for different reasons neither dealt well with people.

On the 19th April 1842, Willoughby and Kate were married in Auckland. They settled in their own place, held parties, dinners and basically lived it up. And this did not change after the Hobsons left and Willoughby acted as Governor.

Isabella complained in a letter to Ellen that she was never invited to Government House. That her daughter Connie had scarcely set foot inside those walls. And that Kate showed no signs of ‘starting something’ months after the wedding.

Which shows that Isabella was not in Kate’s confidence.

There never were any children. When Willoughby moved on to Nevin, Kate went to Courtlands, the family estate in Devon. Later, Ellen’s daughter Isabella McDouall moved in with her so she was not alone. In fact, she may have had some happy years.

But she never again had the close companionship that she’d had with her sister in those early years.

In my tree, she looks like this. Larger than life, and yet faceless in the midst of a family of assertive individuals. Maybe I’ve corrected the imbalance with this blog post. I hope so.

References

- Matt Lemmon from Colorado, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Cartoon by Grandville: Cholera Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org “Chut! Il souffre horriblement du cholera.” Cartoon By: GrandvilleMoeurs Intimes, Series 5 Cabanes Published: 1910 Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

- ‘The Black Cholera Comes to the Central Valley of America in the 19th Century – 1832, 1849, and Later’, Daly, Walter J., published in ‘Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association’ via website https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2394684/

- Dublin Four Courts Alphonse Dousseau, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Botany Bay National Park. Maksym Kozlenko, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Winterslow mountains Michal Klajban, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons