Back to Alice’s Train Journey Part One – Perth to Northam

Back to Adventurous Alice Part Three – A Single Young Woman in Western Australia

Continue to Alice’s Train Journey Part Three – Southern Cross to Kalgoorlie

Skip Forward to Adventurous Alice – A Single Young Woman in Kalgoorlie

Victorian Railways photograph of New A 398 leading a B class up Glenroy Bank on the Sydney Express, circa 1900.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_and_B_class_VR_locomotives.jpg

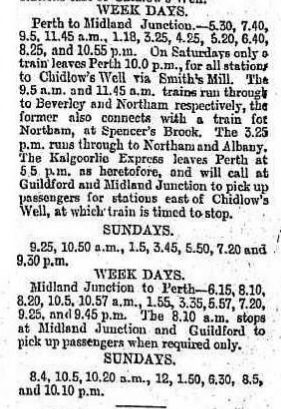

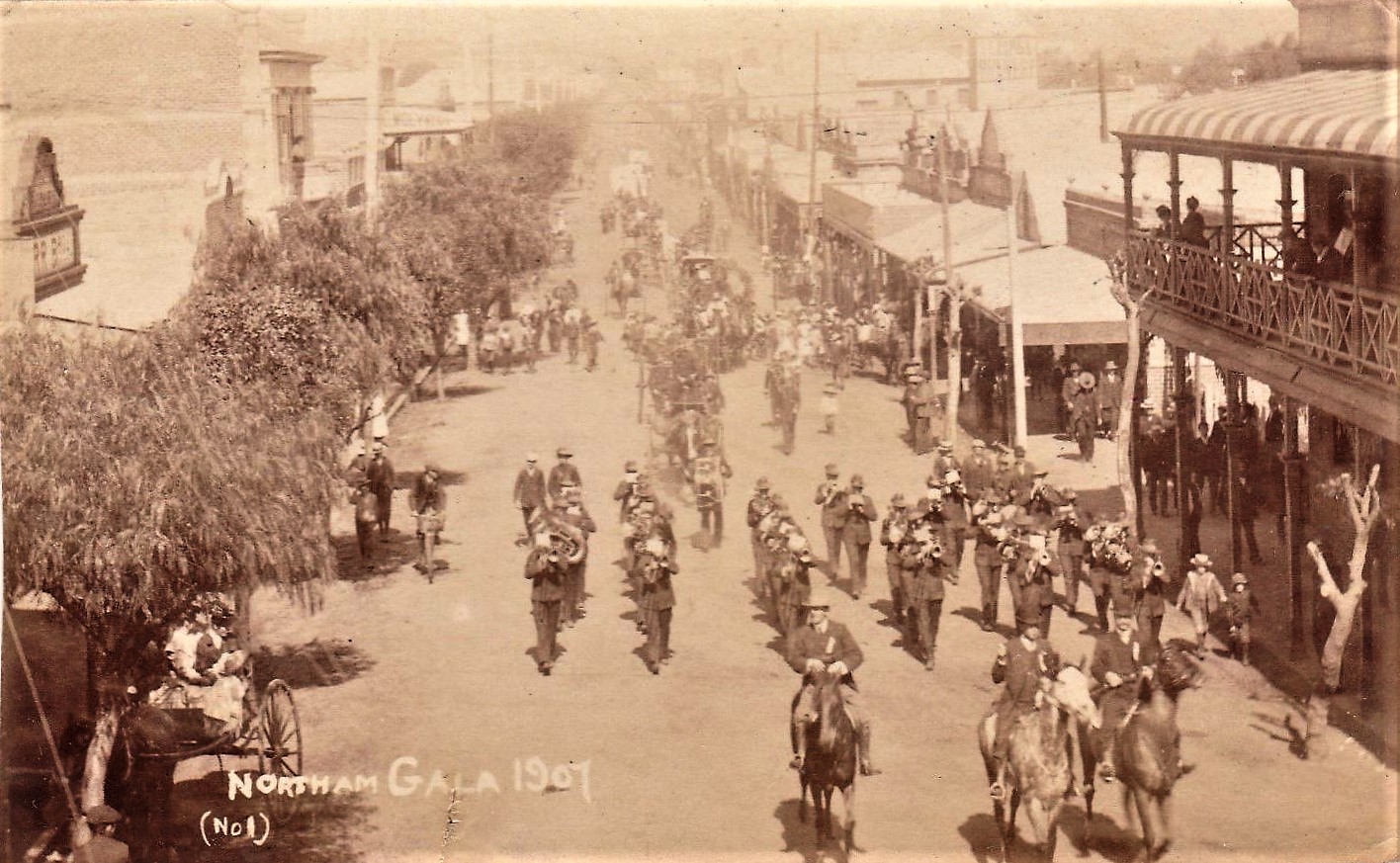

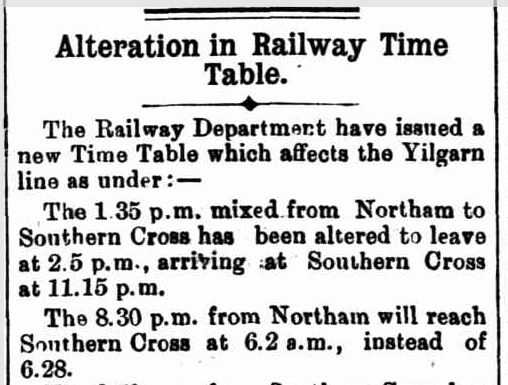

Now at Northam, Florrie and Alice were ready to board the train to Kalgoorlie. They may have been travelling on the newly rebranded Kalgoorlie Express (still commonly referred to as the Coolgardie Express) or they may have been travelling on the ‘mixed’ train which stopped at all stations and pulled freight, so was slower – but much cheaper.

A timetable was published in the ‘Northam Advertiser’ in 1896 which seems to have continued till July 1897.

“Alteration in Railway Time Table.” The Northam Advertiser (WA : 1895 – 1918; 1948 – 1955) 14 September 1895: 1 (Supplement to The Northam Advertiser). Web. 23 Apr 2018

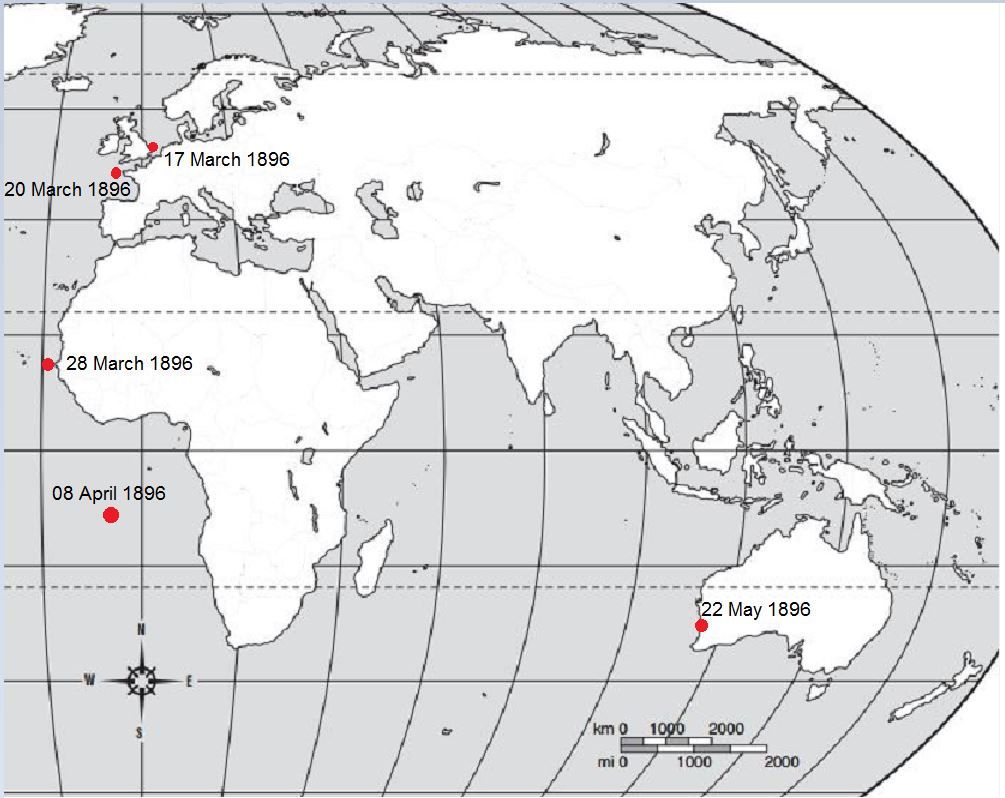

The map below shows that Southern Cross was about the halfway point from Northam to Kalgoorlie. I have finally found a reference to sleeping carriages. They may have comfortably slept for some of the time.

Following the railway journey is a convenient way to describe the world that Alice was travelling to, so this part is as much about Western Australia at the time than about Alice herself.

The ‘Western Mail‘ in 1913 has a picture of the Northam rail yards. Due to copyright restrictions I can’t post it in this blog, but it can be accessed here.

Railway Perth to Kalgoorlie marking in stops referenced in local newspapers at the time as being on the route. It is a little different to the rail line today.

SIR,-That portion of the Yilgarn Railway from Northam to Killeberrin, a distance of about 60 miles, is made to pass over some of the most wretched country to be found in the Eastern districts, being mostly sand plains and some miserable thickets where not even a rat could find a living. The contractor who is building this line has carriages attached for the conveyance of passengers as far as Booracoppin, 51 miles from the Cross, at one pound per head. Fortunately this train does not leave Northam until about ten at night, so that the passengers are not able to see the nakedness of the land. It certainly will be advisable when the Government takes over this line to continue running that portion of the line at night so that strangers may not see what a miserable piece of country they are passing through. When travelling down this dreary line of railway one may cast a reflective glance over the distant landscape and see nothing but a vast sandy desert, and would naturally wonder why a railway was built through such a vile piece of country … This line of railway will certainly be a lasting memento of the errors of the present Ministry, who seem to consider that their opinion and knowledge of the country is supreme.Yours, etc.,W. M. PARKER.York, February 5. (1)

Hay carting to chaff cutting plant, Meckering, 1933, held by State Library of WA. Some rights reserved https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/ . No changes made.

DECEMBER 1896: At the time the Northam-Southern Cross railway was in course of construction, somewhere about 300 men were kept constantly employed. For many miles they worked over some of the richest land in West Australia, and one would naturally expect that some enthusiasm might have come of them … But they were not of that sort. They worked hard and received their pay every fortnight … No desire to settle on the land seemed to possess them … they were men who had worked at navvying jobs nearly all over Australia. Wherever public money was being spent these men rolled up their swags and went to. As soon as the works were done they rolled up their swags and trikked, as the Boers say, for new pastures where big contracts spelt many navvies wanted.

Wages are high and the labour market until lately was entirely in favour of the workers. The demands for the goldfields alone brought thousands to our shores. Didthey settle on the soil? Not 1 per cent.(2)

Kellerberrin. Held by Don Pugh via Flickr. Some rights reserved https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/ . No changes made.

I agree that extensive ring-barking by Government should be undoubtedly remunerative; but not more than two-thirds of the timber should be killed, and only on every second lot of say 1,000 acres ring-barked, and 500 or so left ; selectors to take a portion of each. Besides, in places where there is much stone and little grass all the timber should be left, so as to secure timber for fencing and fuel, shade, and shelter, and to prevent a repetition of an important mistake, frequently made in the Eastern colonies. (3)

In describing the lands in these districts suitable for cultivation, one is met at the outset with a very peculiar difficulty. The nature of the country changes in a few yards. In one minute one is traversing rich red clay soils, the next he is ploughing his way through heavy sand plains. There is no shape or sense of order in the distribution of the various lands. They seem to be scattered about in the greatest of disorder [but]

this area is intersected by the Coolgardie railway, and has a portion of … rich forest … extending between Merredin and Hine’s Hill. The best way of inspecting this area is to travel by train to Hine’s Hill station, where accommodation is procurable at the railway refreshment rooms located there. The rich lands come right up to the station, but the [best] area begins about two miles away. (4)

View of the Doodlakine Store, Station Street, Doodlakine, Western Australia taken 29 december 2014 by Bahnfrend, some rights reserved under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.sv . No changes made.

NOVEMBER 1897: THE NEW AGRICULTURAL PROVINCE.There is a new agricultural province opening up in tho east that very few have seen. The men who, carrying blankets, are looking for work know all about it, but the railway traveller who pries no further than the view from his carriage window, sees nothing beyond an almost unbroken line of forest that is bare of grass, monotonous and forbidding. But behind those walls of gaunt eucalyptus that jostle each other for standing room there is activity, development, fruition. The new agricultural province is in the rough, and it is only to be seen under difficulties. There are few roads, no hotels.You should not set out without carrying tucker, a waterbag and a rug.At the time of the completion of the Coolgardie railway the settlers between Meckering and Southern Cross could be counted on the fingers of the hands, if not on one hand. These pioneers were graziers whose mainstay was sheep. They had the whole country side under pastoral leasehold, and only grew crop enough for their own needs, for till the line was made they could not cope to sell anything that could not walk to market on four legs.When the Lands Department began to survey agricultural areas there was at first a very baiting response on the part of applicants for the blocks … To-day there are only two blocks on the Meckering agricultural area unalienated, and they consist of sand plain, which is considered worthless.… It is anticipated that the Minister … will have the territory surveyed and thrown open for application as Free Homestead Farms and conditional purchases. Going further on towards the Cross there is plenty of unoccupied land at Kellerberrin, Doodlekine, and Hine’s Hill, where some farms have already been established, and fruit trees and vines are doing well, particularly in the vicinity of soaks. But at present Tammin, Kellerberrin, Doodlekine, and Hine’s Hill are to Meckering whatMeckering was to Northam a few years ago, when graziers had a monopoly of the ground that this spring was green with waving corn. Settlers, as a rule, want to see ground proved before they will go out to new country. (5)

Rest area at Hine’s Hill showing the terrain and climate. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rest_area,_Hines_Hill,_2014.JPGBy Bahnfrend [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons . No changes made.

SIR,-I wish to draw the attention of the heads of the various Government departments to the several inconveniences to the travelling public on the Yilgarn railway. The first Two-refer to is the disgraceful way the Railway Department cater for the second-class passengers. It is a great infliction to anyone travelling eves a short distance in one of tbsir carriages. How must it be to poor women and children to travel from Perth to Coolgardie? No cushions are provided-nothing of any description but the bare, hardboard, as naked and as hard as the cell of a gaol ! The cost of cushions for each train would not be more than £10. It is a common occurrence for the carriages to travel the greater part of the journey at night time without any light, and this gives an opportunity for criminals of desperate character to commit crime. To obviate this I would suggest that relays, of lamps be kept filled and lighted at Hine’s Hill for the passenger trains. The ladies’ waiting-room at Hine’s Hill might as well be at the Gulf of Carpentaria as where it is. It is impossible for a lady to find it unless shown. The waitresses are too busy attending to the tables to show them, and I have often heard ladies asking the men standing on the platform to show them. The waiting room is found by entering, the refreshment room and travelling along its whole length directly behind the chairs of the passengers seated at table, with scarcely room to pass down. Why not have the waiting-room on the platform, with a notice on the door directly opposite where the passengers leave the trains? … Another question I wish to ask is, Why do not the Postal Department have a telegraph station at Hine’s Hill? The travelling public severely feel the want of this. The passenger train stops half an hour there for refreshments, while at Kellerberrin, where the telegraph station is, the train stays but a very few minutes, and the passengers have to travel about three chains to the office.-Yours etc,MAURICE WILLIAMS.Hine’s Hill, October 2 1896 (6)

DISORGANISATION.THE RAILWAY BETWEEN NORTHAM AND SOUTHERN CROSS.It has come to our knowledge that a deplorable state of affairs exists on the Government railway line between Northam and Southern Cross, and, in all probability, no improvement will be enacted until some disaster takes place. Our informant is a gentleman well known in the city, who has frequent reason to adopt transit by rail over that line. He says that the time-tables have been suspended between those two stations, and it is now a matter of very common occurrence for trains to meet when mid-way between two stations. The result is that one has to back to the station where the line happens to be duplicated, and allow the other to pass it there.(7)

ALONG THE NORTHAM-COOLGARDIE RAILWAY.DOODLAKINE AND MOORANOPPIN.Leaving the Bainding Agricultural Area and travelling west immediately on passing the Hine’s Hill railway station, one comes across a salt lake. This will be found, on close examination, to be part of a series of salt lakes from which one of the branches of the Avon River takes its origin. In a devious manner this chain of salt lakes travels south-westerly ,from Hine’s Hill passing immediately under Mt Caroline. Several large patches of first class forest land impinge on to it … Following the old coach road from Hine’s Hill Railway Station and travelling west, a distance of three miles brings the traveller into a fine forest of morrell, gimlet and salmon gum timber … The bed of the lakes in many places is covered with fine salt bush … (8)

Southern Cross, along the train line from Perth to Kalgoorlie.

- “THE COUNTRY ALONG THE NORTHAM-YILGARN RAILWAY.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 7 February 1894: 6. Web. 23 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3057839>.

- “OUR AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 14 December 1896: 2. Web. 27 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3103960>.

- “OUR AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 14 January 1897: 9. Web. 27 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3105570>.

- “OUR AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 2 January 1897: 7. Web. 27 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3104993>

- “THE WIMMERA OF THE WEST.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 29 November 1897: 3. Web. 23 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3189009>.

- “RAILWAY TRAVELLERS WANTS.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 7 October 1896: 9. Web. 27 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3100406>.

- “DISORGANISATION.” The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 – 1901) 21 February 1896: 9. Web. 27 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72379490>.

- “OUR AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 9 January 1897: 11. Web. 27 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3105330>