This is the story of a family named Brown.

There’s a struggle most family historians will know. You spend years poring over records, identifying the ancestor, working on that jump back to the previous generation. Hoping that the unknown parents will turn out to be Winterfink or Albercoyle, something searchable that will stand out in lists and newspaper articles and interment records. Names like Brown or Smith can doom an ancestor to permanent obscurity.

My ancestors were John and Mary Brown, married 1760 in Fordham, Cambridgeshire.

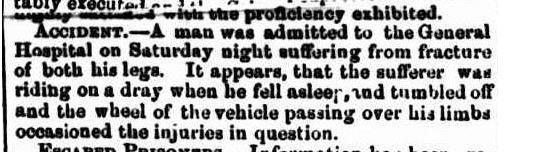

As it happens they were more visible than expected, partly due to their grandson Robert born 1818. He was transported to Australia as a convict so we know a lot about him. Not only that, he lived a very long life among family equally blessed with longevity so the oral history is good. Robert Brown died in 1911, his son died in the 1950s.

Tracing the family back from Robert to his father Benjamin was simple. Benjamin (born 1785) married Susan (Susannah) Sargent, the names are unique enough, we have them in every British census and could build their family with ease. They spent their entire lives in the same region, which helped a lot. They were labourers, farmers, ploughmen. Agricultural pursuits right through. Our Robert seems to have been the only black sheep, the others appear fleetingly through births, marriages, death and census. A quiet and excessively numerous family.

The complication was Suffolk. Fordham is right there by the border and while Cambridgeshire records are available online, Suffolk is a great challenge for anyone not on the ground. Benjamin came from Fordham, his wife Susan from Exning. Susan was a brick wall for many years because of this.

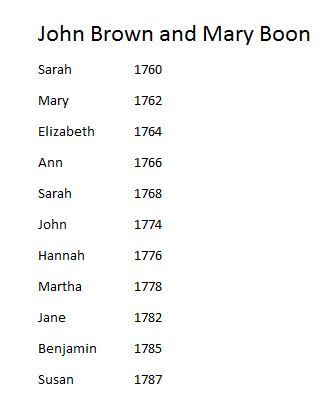

Focusing on Fordham, Benjamin was the son of John and Mary Brown nee Boon.

Here is the whole family:

This may be incomplete. Eleven children seems like quite enough but there is a suspicious gap between Sarah No. 2 and John. There’s room for two more children there.

It’s complicated from here on in. For clarity, John Brown’s parents are referred to as ‘Granddad John’ and ‘Grandma Sarah’. John and Mary’s same name children are John Jr and Mary Jr.

We can only guess at the size of their house. Granddad John lived for some years in Landwade but was buried 1772 in Fordham, so he might have lived with them too.

A few generations earlier the Browns owned land and had wills, so our John Brown might have lived on his own land too. But his children clearly lived in rental places and there’s no indication land was passed on to any of them.

It was probably lucky that the eldest children in the family were girls. By the time their mother reached her less energetic middle years when pregnancy is harder and childbirth even more risky, she had a group of capable youngsters able to take the load on their own shoulders.

The first Sarah died at the age of six and was buried on 1st December 1767 in Fordham. She was the only child they lost.

John Junior was baptised on 27 November 1774, not long after the death of Granddad John. There was probably some rejoicing or at least relief that the head of this household would finally have someone to help with heavy work and take over the household if need be. Maybe they held their breath until he survived that dangerous first year. But the baby was hale and hearty, it seems, and grew up just fine.

Baby John had a bevy of personal carers in Mary (12), Elizabeth (10), Ann (8) and Sarah (6). That’s if Mary was still around; girls in this region were commonly out at work by the age of 11.

John was the only son for some time. His birth was followed by Hannah and Martha, and by now the eldest daughters were young adults, probably doing farm work or in service around the district.

Child number nine was Jane, baptised on 30th June 1782. She was six months old when her eldest sister was married.

The marriage was straightforward like everything else in the life of this family. Mary Jr was about to turn twenty. No doubt a capable home manager, experienced in childcare, she knew how to cook and sew and milk cows and nurse children through fevers and all those things required of a farmer’s wife in 1782. So when local man John Munns looked for a wife she was going to be a strong contender.

The Munns family, like the Browns and the Sargents, jumped across the county border between Fordham, Landwade and Exning. I’m not sure which side of the border they began on. I actually think we’ll find an earlier Munns link, maybe they were connected to Mary Boon. There’s a good chance young Mary Brown and John Munns knew each other their entire lives.

I imagine they announced their engagement and made plans. The marriage took place on the 18th November 1782. Everything respectable and straightforward.

I learned about Mary’s marriage through DNA matches with three of her descendants.

Two years later, Ann Brown formalised her union with farmer John Burling of Swaffham Prior, a village six miles from Fordham, three miles from Exning. It wasn’t a big move, but a good one socially and economically. John was a landowner in a modest way and his farm was quite successful.

I discovered Ann through another DNA match.

From this point on, the generations are slightly muddled. John and Mary Brown’s tenth child – their second son Benjamin – was baptised in the same week as Mary Jr’s apparent first child Henry Munns, and also John and Ann Burling’s first child Susannah.

At a calculated guess based on ages and proximity through the decades, I would say Benjamin Brown grew up playing with his nephew Henry Munns and his cousin William Brown. And the Sergeants/Sargents were there too, not yet married into the family but at all the social events. As were the Burlings.

This is the time to introduce William and Mary Sergeant of Exning.

William Sergeant and Mary Levett were married in 1778 and their eldest son John was born the same year. George, Susannah, William and Mary were born over the next few years, followed finally by Elizabeth, James and Eleanor. They lived in Exning and mostly stayed there, but they attended Brown weddings and the families knew each other well.

This, as far as I can see, is what English village life really was. Not individual families as we do it today, the whole population personally connected again and again. I’ve kept it simple so far.

In 1787, Susan Brown’s birth completed the family of John and Mary Brown. In this same year, little Susannah Burling was buried and a new Burling daughter was given the same name.

By 1788, Elizabeth Brown must have felt like an old maid. There she was aged 24, nieces and nephew popping up everywhere (Mary Munns and Isaac Burling came into the world this year). But finally it was time for her own wedding. She married John Frost in Isleham, Cambridgeshire.

I have DNA matches with Elizabeth’s descendants too.

Sarah may have married in Isleham too, there is a plausible marriage with John Peachey on 24th October, 1787. But I cannot be sure of it.

So having introduced all the characters now, we can pull the whole thing together. Mary Munns, Elizabeth Frost, Ann Burling and Sarah Peachey(?) are settled. There’s a gap now, which matches that six year child gap between Sarah and John. The four married daughters increased their families significantly. The Sergeant children are likewise growing up

On 27th September 1798, John Brown Junior was married to Ann Shinn in Fordham. He may have felt some pressure to do so, his father was sixty years old and probably starting to ail.

It was another time of rapid change. Hannah married Thomas Bishop in 1799 (DNA matches brought this to light), then came the death of John Brown, father and grandfather to this giant family. He was buried in the Fordham cemetery on 10th April 1801.

A year later was the first union with the Sergeant family through the marriage of Martha Brown and John, the eldest Sergeant boy. They spent a couple of years in Suffolk before moving to Fordham.

I discovered Martha through DNA matches too.

To conclude this part of their history, Benjamin Brown married Susan(nah) Sergeant in 1810, while Jane married William Durrant four years later. I have not located a marriage for Susan.

There’s just one more marriage to add.

The fifth Sergeant child was Mary, born a year later than my Benjamin, baptised 09th October 1786 in Exning.

Mary Sargent married Henry Munns, the eldest son of John Munns and Mary Brown.

It is confusing. John Sergeant married Martha Brown. Susan Sergeant married Benjamin Brown. Mary Sergeant married Henry Munns. You can see how I might have strong matches with other descendants of this family. But I also have matches with descendants of Eleanor Sergeant who married an Andrews, and with Burlings and Frosts and Bishops so it’s not just endogamy from that particular grouping.

In conclusion, this is the family of John and Mary Brown as I now know it, a long way ahead from my first post about the family. I wrote this first to help others researching this family, and second to show what DNA matching can achieve.

Now I’ll get on with more research.

Image captions:

1 Image by Bob Jones : Track near Fordham, from Wikimedia CC BY-SA 2.0 .No changes made.

2 Robert Brown born 1818 with grandchildren Lucy, Amy and Mary in Australia.

3 George Stubbs: Haymakers 1785 (public domain)

4 John Constable’s Wivenhoe Park, Essex showing rural features. There are very few paintings featuring Cambridgeshire.

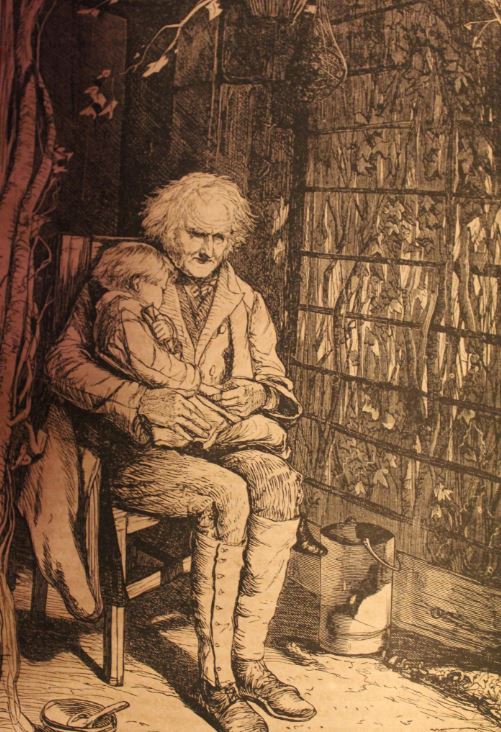

5 Old man Family Hour Magazine 1854

6. I chose this image for the mud. Very much a part of British farming.