The Ballangarry Mine, owned by Herbert Dunstall who is almost certainly in this photograph. Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), Tuesday 1 August 1905, page 24

This is a semi-fictional account, although the included facts are accurate as far as we know.

The details come from oral histories and from archived records. Herbert and Alice were married in Kalgoorlie in 1899 and their son Kenneth was born there in 1900. They were a pair of intelligent, capable young adults who shared a dream of breaking free from the poverty and overwork that had destroyed their parents. In late 1900, Herbert purchased the Ballangarry Gold Mine at Lake Darlot. Alice planned to operate a boarding house, having observed the profits made in that industry in Kalgoorlie. In late 1901, Herbert and Alice became the proprietors of the Ballangarry Hotel, taking over from William (Wes) Beal(e) after his untimely demise from kidney failure at the age of 39 years .

In 1901, Herbert, Alice and baby Kenneth made the long journey into one of the harshest environments in all of Australia.

Red dust. Swirling in the air and catching in her mouth, in her hair, in the sweaty cracks between her fingers. Rivulets of sweat trickled down her back and soaked into her sturdy shirt. It was always a tough decision – thick clothes to protect against scratchy branches or thin clothes to stay cool. Perched on a swaying camel tied into the middle of a camel train, Mrs Alice Dunstall reminded herself that all trials eventually come to an end.

She wiped sweat from her forehead. Kenny was a heavy red faced lump dozing against her chest. He was tied to her, not pleasant for either of them in this afternoon heat but the only way to keep him safe for the journey. A camel back ride was tough enough without holding a baby at the same time. The Aboriginal women in Boulder had taught her the tying trick. They’d loved him. They always loved babies.

She turned to look behind at Herbert. He was staring dreamily off into the horizon with the sweat-dampened map open in his hands, unaware of the dirt or the heat or the insects buzzing in his ears. His shirt was unbuttoned at the collar and he’d rolled up the sleeves. He looked quite relaxed on the back of a camel in the scorching heat.

She brushed the flies from Kenny’s face and Herbert noticed the movement. He gave her a dazzling smile and nodded towards the west. Alice followed his eyes and recognised the shape of the hill from their map. Herbert’s new mine was there. He’d bought it in Kalgoorlie from a fellow who’d had enough of loneliness. That wouldn’t happen to Herbert. He was a solitary man who lived more in his own head than in the outer world.

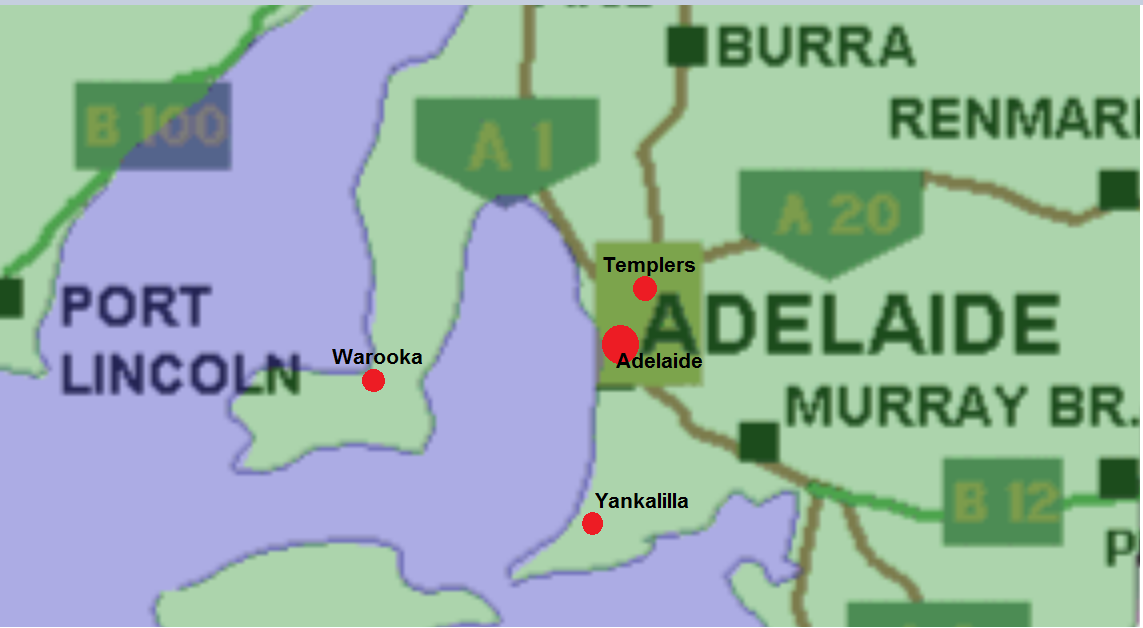

Lake Darlot’s location in the East Murchison Gold Field. Map of the West Australian goldfields 1896 : Coolgardie to Lake Darlot / compiled by J. T. Buxton, Coolgardie. Out of copyright.

With a lurch, the camels changed step. She grabbed for the pommel with one hand and cupped the other round Kenny’s head. They had topped a rise. Now it was a long descent to – to what? Was it rooftops before them? The hard bare land stretched in all directions like an ocean in sunset, perforated by stunted trees and shadowy hollows that might be caves. Sweat dripped into her eyes and her cheek stung. She was burned, even with her broad-brimmed hat.

Was there a lake at Lake Darlot? Sometimes there was, she had been told. When the rains came the place turned green in a matter of days. It was because of the rains that they were coming in by camel. Five months ago the greatest flood ever known in the region had washed away the cart track and even now the eroded surface was all but impassable. The long, slow journey by steam train from Boulder to Leonora had been an adventure. This stretch was rapidly losing its charm.

After the rains came the water soaked into the ground in a matter of days. The skies powdered into a harsh blue and the red ground reasserted its supremacy. She had seen it already, right across Western Australia. In her childhood she had known swirling white fog over the Thames in an English world of winter, cloaking the buildings until it seemed as if no other person could be found in the county at all. This was the same scene painted in different hue. Maybe those empty-seeming hills were as peopled as the world she had left? Maybe locals were watching them even now?

The descent was bumpy and Kenny woke with a sad, croaking drizzle. She pulled out the water bottle and splashed a few warm drops into his mouth. At eight months he needed to drink more, but she wouldn’t feed him now. The buildings before them were taking shape – squat wooden structures quickly erected in the new little mining town and a main street taking form with tall, graceful houses of stone. Faces stared from doorways as they passed.

Map of the West Australian goldfields 1896 : Coolgardie to Lake Darlot / compiled by J. T. Buxton, Coolgardie. Out of copyright.

The Ballangarry Hotel was a low, long building walled in painted iron sheets with a wide verandah. It was a very welcome sight on a hot afternoon. The camel driver gave a bellow and Alice clung for dear life as her mount lowered itself into a kneeling position. An Aboriginal woman came out from the hotel verandah and reached out a hand to touch Kenny’s cheek. The woman said something that Alice did not understand. Alice nodded slowly and smiled. She did not know the language but the sentiment was clear.

A portly man appeared then, his white skin a strong contrast to the woman’s. He reached out a hand to help her off the camel. Alice very stiffly forced her limbs into motion.

“You’d have to be Mrs Dunstall.” he greeted her. “Welcome to our little town.” He had a wheeze in his voice. “Wes Beal, proprietor.”

Herbert came to stand beside her. “How long before nightfall?” He asked.

Alice gave him a sharp look. “There’s no time to see the mine this afternoon, Herb. We have to release the camels or they’ll charge us another day.”

Wes chuckled and nodded. “They have us over a barrel, these Afghans, and they know it. They’re richer than the rest of us all together. Got to admit, they’ve been invaluable to the Ballangarry. Would you like to step indoors, Mrs Dunstall?”

Oh, how Alice wanted to step indoors! “I’ll just watch the unloading first.” she said with a sigh. Herbert was too dreamy, all kinds of tradesmen took advantage of him.

Week (Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 – 1934), Friday 29 August 1930, page 2

The Aboriginal woman made an arm gesture, offering to hold Kenny. Alice threw her a grateful look and untied the wrap. The woman reached out eager arms. She knew just how to hold a baby. She stared with fascination at Kenny’s face.

“Kenny.” Alice touched her son’s head. The woman smiled. “Kenneh.”

Close enough. Alice pointed to herself. “Alice.”

The woman frowned. “Ah – Ale.” Then she pointed to herself. “Ehggei.”

“Ehggei.” Alcie repeated. The woman’s eyes narrowed. “Ehggei” She repeated.

After three attempts, Alice still hadn’t got it right but had come closest with ‘Egg’. They smiled at each other in satisfaction. Ale and Egg.

With the camels unloaded and some local miner’s sons earning a few pennies bringing the goods indoors, Alice finally entered the spacious interior of the hotel with her husband, her son and her new friend Egg.