Due to a regional telecommunications problem, I have spend the week with very little internet connection. This gave me time to dig out some paper records which I’ve had sitting in my cupboard just waiting for a time like this. I’m an avid collector of records and an avid creator of notes. Wherever I go, I take a notebook and a camera. If ever I learn the history of a house, or a field, or the old car sitting in someone’s paddock, I take a photo and jot the story. I also sketch the floor plans of old buildings. You never know when it will slot into the family tree. It’s also a wonderful piece of family history to give, if I find the person who does belong to that story. Networking is a big part of family history research. We are just one giant team.

After going through some of my paper records and another folder of previously-untouched digital records (eg photographs of objects and documents that I have snapped but not processed) my family database grew by some 285 names.

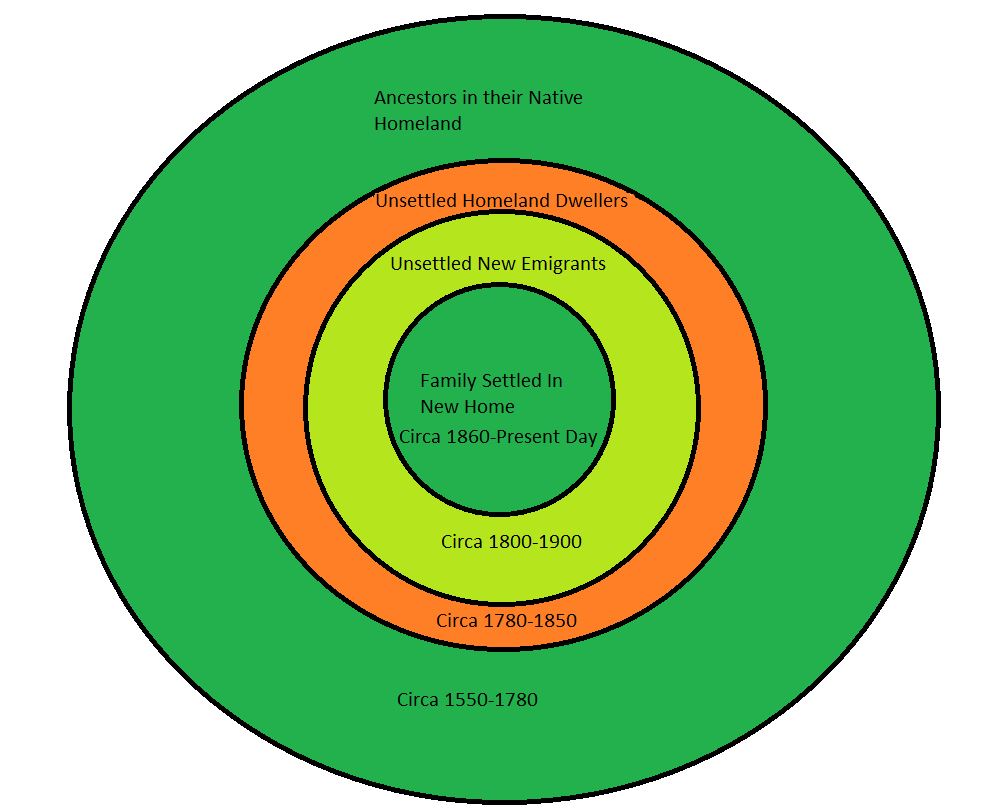

I have mentioned before that my objective was first to identify point of entry to Australia for each ancestor, and reason for it, and secondly the actual homeland of each emigrating ancestor. I have a kind of colour-coded image in my mind.

At a very basic level, every family line that I have tells the same story. They lived somewhere for centuries – forged a satisfactory existence, managed to raise children to adulthood in times of hardship, plague, mini ice-age, intolerance of minorities and women. It doesn’t matter which continent you look at, all had periods like this. Only the strong, well-supported and well-nourished could survive. Only those with a modicum of intelligence and adaptability could survive. Mortality rates amongst children and child-bearing women were extremely high. If someone crumbled under the strain, became physically ill or went mad, unless they had a family around them with the resources to help, their dependents went down with them.

All of our ancestors survived this time, obviously since we are here. Therefore, all of our ancestors were basically in stable environments and had the resources available to them to survive the hazards. Generally they stayed where they were for centuries. I can only know for sure about the time after parish records began, but from that time – around 1550 – to the late 1700s, my ancestral lines stayed put. One lot in Dorset, one in Somerset, one in Sussex, one in Essex etc etc. Their lives revolved around small clusters of villages with one or two market towns. There may have been soldiers or noblemen who travelled, but even they tended to leave their family at the family home.

Then, sometime late in the 1700s, the industrial revolution and better infrastructure changed all this. Once the roads improved people started travelling – for work, for adventure, to escape their reputation, to escape a bad situation. Anyone researching English ancestry will know all about this – as the industrial revolution took hold, country folk went to the cities for work and city folk fled to the country for their health. The population boomed, employment dropped, life became unsustainable for many and they roamed further and further from home in search of food and shelter. These ancestors are a barrier to the researcher. Even if you find them in a UK census, ten years earlier they were in a whole different county and in 1841 for the first census they were still not in their ancestral homeland. I consider these the ‘Unsettled Homelanders’ because they are at least in their native country. Displaced and separated but still there. Those who did not experience this remained as they were and did not need to emigrate.

This era of research is a trap for the unwary and inexperienced genealogist, at least for those descended from emigrating families. A lot of early books on the subject told us that the English, Irish and Scottish left their home towns and emigrated to the colonies for a better life. Many researchers have located emigration records which list eg Liverpool or Lancaster as that ancestor’s birthplace and have assumed this meant they have ancestral roots there.

Once we have researched for a while we know better. Places such as Liverpool, Lancaster, Plymouth, Portsea/Gosport, Dublin, Limerick, Tower Hamlets …. You find those locations popping up, you know there’s a challenge ahead of you. These were gateway ports for emigrants and military. Not many families spent much time there. It’s hard to get behind with any degree of certainty. They were there for one generation, trying to make a go of it – watching the emigrants leave perhaps weekly or even daily. They arrived as a young couple and had their children there, hence the birth location. That doesn’t mean the parents were born anywhere close.

Cooking by campfire – a reality for early colonial families until they had built their home. It must have taken constant observation to ensure young children did not come too close.

Once the ancestor has emigrated comes another unsettled time. Most took to their new land grant/purchase with zest, very eager to establish themselves and put the struggle behind them, but once the initial excitement faded, they took a second look at what they had. The colonies of the Americas, Canada and Australia had a wide range of climates and conditions and it usually took time for a new family to locate somewhere that worked for them. Van Diemen’s Land was beautiful if you could handle the cold and did not suffer from asthma. South Australia was excellent for anyone with fishing skills or drought-resistant farming methods. Queensland with its monsoon season required a different set of skills altogether.

As a result, it was often the second or third location that a family settled in. I had one early brickwall, a long term settler family in Tasmania. I failed to locate an emigration record simply because I assumed they must have come direct to Tasmania. As it turned out, they arrived in Adelaide, then after five years trekked to Victoria, and finally made the move south to Tasmania. I’ve learned that lesson well.

Only after this period of early-arrival mobility did families settle on a property and in a district, where the old system basically re-established itself until the newly completed century. It’s good that this happened, for we who delve. We can get back many generations in the same parish register or by visiting the one cemetery.

The many movements of the present generation will be an interesting challenge for genealogists of the future.