On 20th October 1856 a baby boy was born in the small colonial town of Hamilton in Tasmania, Australia.

This was their first year with the name ‘Tasmania’. Until now the town had existed within the British colony of Van Diemen’s Land, but the colony gained the right to self-legislate in 1854 and in 1856 had made some large changes – including the name, in an attempt to shake off the convict stigma. A whole lot of things were altered, including the details which went onto the birth, marriage and death registrations. What England wanted to know about people was not what Tasmania wanted to know. Tasmania was still under British rule, but not under direct British administration.

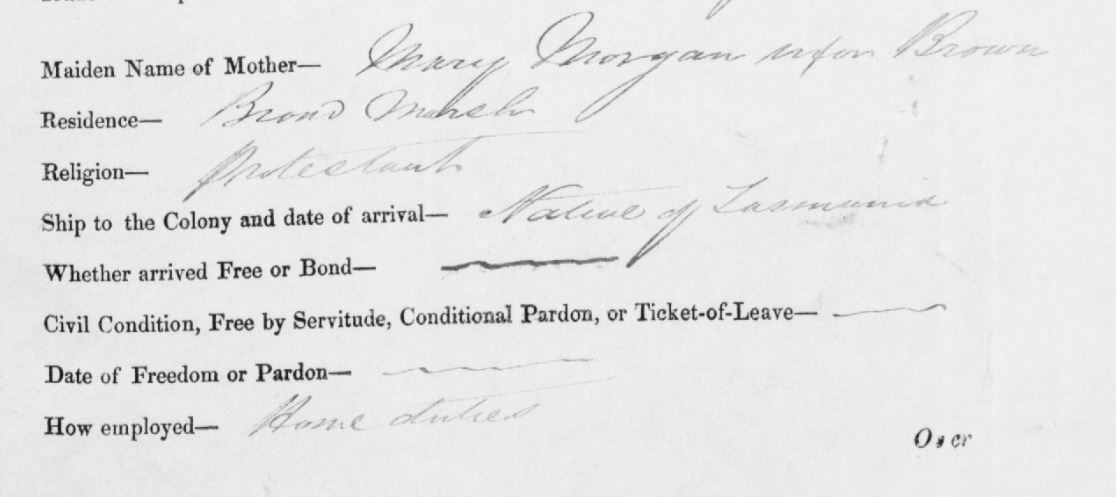

That baby boy was the first child for his parents, as far as we know. He was named Robert after his father, who was Robert Brown, a carter, free by Conditional Pardon, born in Cambridgeshire and now settled in the Tasmanian midlands. The baby’s mother was Mary Brown formerly Morgan, and this is the first definite mention of her in the official records.

By 1856, records in Tasmania were pretty good. In a colony of convicts and a vibrant shipping industry, the authoritative bodies wanted to know who went where. There were still thieves on the run, escapees and persons banned from the urban districts. So how someone could reach the age of adulthood and not find herself on a public record is a bit of a mystery. She is by no means the only one, but as more records are digitized and made available, and as the internet enables family records to be accessed by others, the mysteries are unraveling. Generally, it comes down to an unexpected change in name. A child who took on a stepfather’s surname, for instance. Or someone who came to Tasmania not from overseas but from a neighbouring state like Victoria.

There’s a good chance that Mary has records, but her very name is against us. She began life as Mary Morgan and ended it as Mary Brown. Both are very common names.

It’s miraculous that we could trace Robert Brown, but he left his information everywhere – his name, his accurate age, the ship he arrived on, his home town. He provided consistent details and thus we found him even before records went online. He was transported for life and at first behaved rebelliously, but by 1850 he had received a ticket of leave and by 1853 received his conditional pardon.

A conditional pardon, generally, gave him freedom to live his life under certain conditions – usually that he not return to his native country, or that he not leave his new country.

No record has been found of a marriage between Robert Brown and Mary Morgan, and since marriages were easy to procure back then, it is more likely that they did not formalize their union. However, this in itself is odd in a cultural environment where such things were frowned upon. Of course, if they arrived in a town as an already married couple, no one would know any different.

In 1856, the proud new father was aged 37. We don’t know Mary’s age but she continued bearing children for many years. Following the usual pattern on all paternal sides of my family, she was probably in her mid teens, giving her a birth year of somewhere about 1840. I think between 1835 and 1841 is pretty safe.

Robert and Mary seem to have been healthy and maybe happy too. A second son, William, was born in 1858, still in Hamilton district but I’m not sure if it was in the township. After this the young family moved to Black Brush, later renamed Mangalore, where Robert was employed as a carter. Their third son was John and he was my great great grandfather.

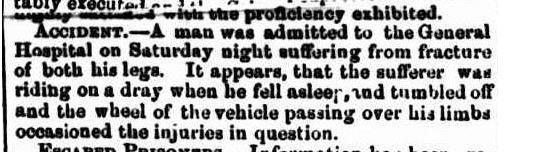

Amelia was born in 1862, and two years later we have a glimpse into their everyday life when Robert, father and breadwinner, was in an accident and broke both his legs. After some searching, I have located a brief description of the accident in a local paper:

“THE MERCURY.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954) 18 Jul 1864: 2. Web. 13 Oct 2014 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8827402>.

I had wondered about the three year gap between baby Amelia, born in 1862, and the next child in 1865. The accident explains everything.

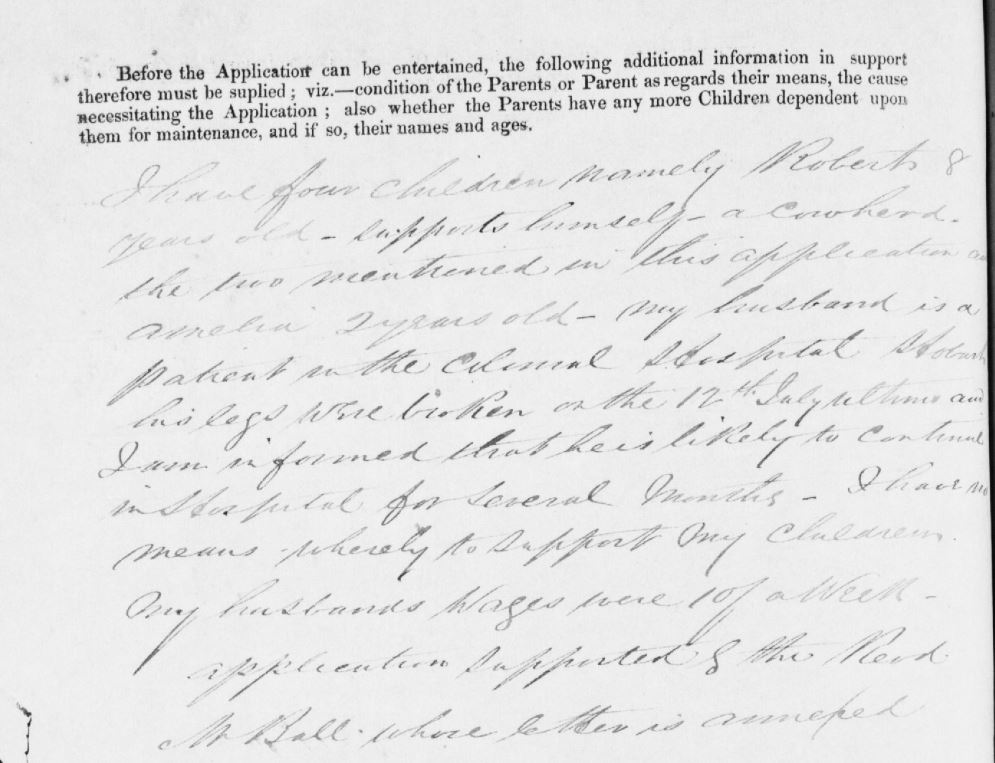

Mary found herself with four young children and no way to earn a living. As people do in that situation, she turned to the minister of her local church who referred her case to the Queen’s Orphan School in Hobart – the state orphanage.

I first saw a brief transcription of this event a few years ago, but it is only recently that I had a chance to view the original – which gives far more detail.

The Orphan School application includes five glorious pages giving us a brief confirmation of this woman’s existence. The greatest detail here – of which we were never sure – is that Mary was native born. This means that she was born within the colony. It is not a reference to aboriginality. Her parents might have come from anywhere else. But it does mean that Mary, to the best of her knowledge at least, was born in Van Diemen’s Land. She didn’t remember any other home. So we need to look at someone surnamed Morgan who was around in circa 1835 who could be her parent. This is still not easy, but nice to know.

Mary’s tale was a sad one, to we who live in a world where children stay children till their teens.

I have four children namely Robert 8 years old – supports himself – a cowherd, the two mentioned in this application (William and John) and Amelia 2 years old – my husband is a patient in the Colonial Hospital Hobart. His legs were broken on the 12th July ultimo and I am informed that he is likely to continue in hospital for several months – I have no means whereby to support my children. My husband’s wages were 1 shilling a week. Application supported by the Rev M Ball whose letter is annexed.

It’s a useful document. The Reverend’s letter certified “That the bearer Mary Brown is the wife of Robert Brown a labourer in this district who was recently received into the Colonial Hospital with both legs broken from an unfortunate accident.” He also confirmed “That she has applied to him to have her three sons Robert, William and John recommended for admission to the Orphan School”

The application was rejected for Robert aged 8 who was deemed able to support himself as a cowherd, and was accepted for 6 year old William and 4 year old John. They were only in there for a few months – until Robert Brown was released from the hospital at the end of October. One wonders if he was able to resume his work as a carter quite that soon, and bring in a wage. I also wonder if the Reverend certified that Mary was married to Robert because he assumed it or if he really knew it.

In 1865, Elizabeth was born, followed by James in 1868, Mary Anne in 1872, Henry in 1875, Frederick in 1878 and Benjamin in 1879. Frederick died young but this was the only child they lost.

The rest lived to adulthood and were married but I have been unable to trace all descendants.

If Mary was still bearing children in 1879, I don’t think she can have been born earlier than 1835. I still think 1840 is more likely.

That birth record for Benjamin is the last mention of Mary Morgan.

For every one of the births, Robert was the informant. It is only the Orphan School application which was undertaken by Mary herself.

Mary Brown died. We can deduce that since she was born in the early 1800s and won’t be alive today. There are 27 deaths for women named Mary Brown between 1879 and 1899. Records are harder to obtain after 1900 for Tasmania.

Of those 27 records, one in New Norfolk in 1899 seems plausible, but it comes with absolutely no details. A private patient at the New Norfolk Hospital and the informant was the superintendent. The hospital reported deaths at the end of each month and they knew little about the patients and only wrote the necessary. This Mary Brown was buried at North Circle cemetery and the burial record is word for word what they received from the hospital – exactly the same as the death record. No headstone remains, the cemetery was badly vandalized through the 1970s and 1980s.

If that is her, it’s a sad and obscure ending for a woman who successfully raised a large family in difficult circumstances.