Oatlands 2014

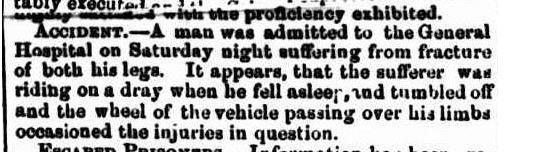

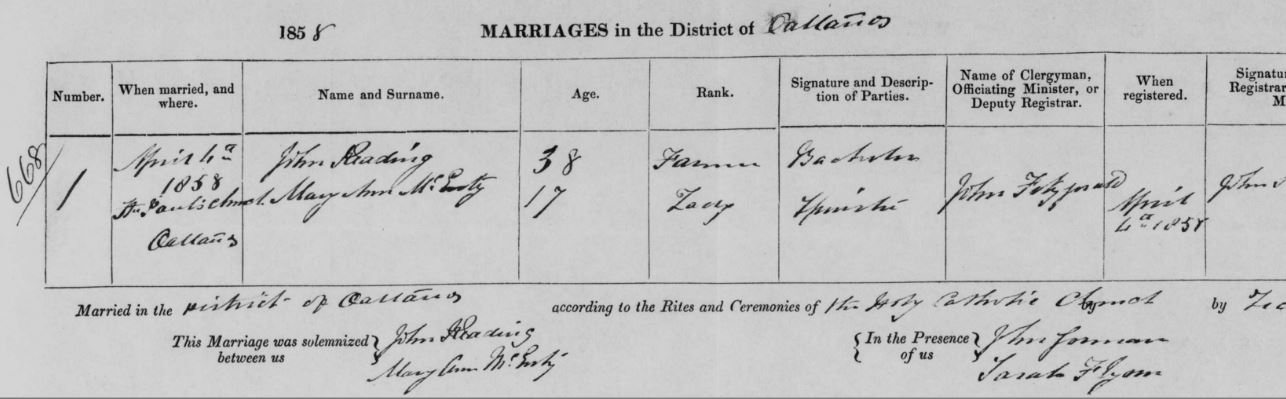

On the 4th of April 1858, John Reading and Mary Ann McGinty were united in Holy Matrimony at St Paul’s Catholic Church in Oatlands, Tasmania. According to the register, John was a farmer and a bachelor, aged 38. Mary Ann was a Lady and a spinster, aged 17. The witnesses were John Gorman and Sarah Flynn.

Here’s the entry:

Tasmania Names website https://stors.tas.gov.au/RGD33-1-58$init=RGD33-1-58p596j2k

It was probably a very pretty wedding. The historic church of St Paul’s is a grand sandstone building, a place anyone would love to be married in. Here it is below.

St. Paul’s Catholic Church, Oatlands. V.D.L: first stone laid 9th April 1850 Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office: Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts. Usage of image allowed for non-commercial use only with attribution included.

The topic of Week 9 is Valentine and I struggled to find a good couple to write about. I’m sure there was plenty of love in my family tree, but life was so different back then, I just don’t think they thought about it that much. Generally speaking, the women needed to marry to have any kind of life at all, whatever their social sphere. The men needed to marry to have any kind of comfort in their life if they were poor, or to fulfil their social obligations if rich. No doubt love came into it, but looking at paper records for my ancestors doesn’t tell me much about their motivations.

John and Mary were my great great grandparents.

John was born in Tipperary, Ireland as John Reddan in 1820. This detail comes from later records. His father was Darby Reddan and his mother was named Bess. He grew up in a time of poverty and conflict and as an adult became a soldier. His name at attestation was recorded as John Redden.

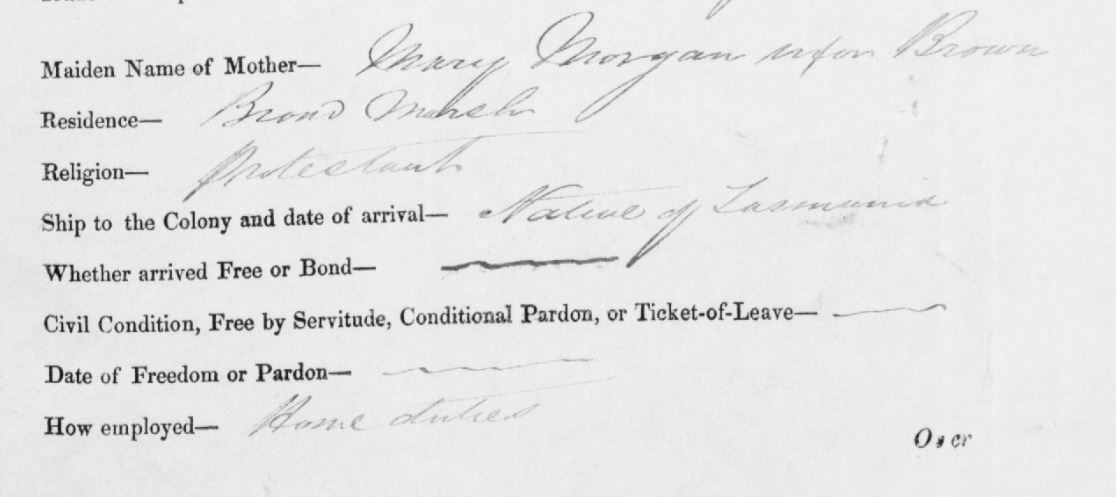

He traveled to Canada with the 97th Regiment in about 1839. He spent ten years there. From the little bit I have read about the 97th Regiment and their experiences, it was very cold, very damp, very miserable. In 1849 John deserted, was excused, but then deserted again. He was found, charged with desertion and transported to Van Diemen’s Land as a convict. His transportation record is recorded as John Reddin. Upon receiving a ticket of leave after only two years, John became a constable in the Green Ponds region. He would have met ellow constable John McKinley, who was a transported convict from Donegal. He obviously also met John’s daughter Mary Ann.

Ruins near Oatlands, Tasmania 2014

John McKinley and his wife Alice came from Fermanagh in Ireland. A young couple with two toddlers and a completely clean record, they committed a crime together and were tried together. John was sentenced to transportation, Alice was deemed to have acted under the influence of her husband and was let off.

Alice committed another offence – larceny – days after her release. This time she was sentenced to transportation. It is very clear that the plan was orchestrated. They were transported on different ships a year apart.

Alice and her toddlers Mary and James arrived on the Waverley in July 1847. Both children survived the journey but tragically James died in the convict nursery at Dynnyrne – a place infamous for its disease and neglect of the children. Mary was sent to the Orphan School while her mother completed her sentence.

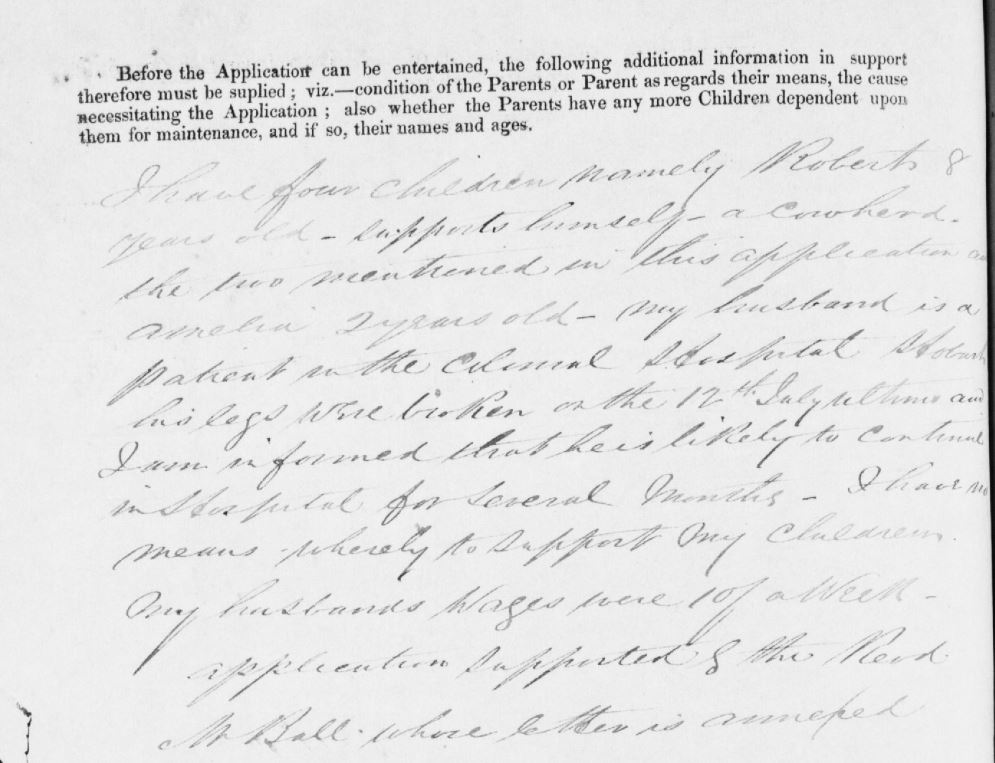

Orphan School Transcription – original can be found at Archives of Tasmania – transcription at http://www.orphanschool.org.au/showorphan.php?orphan_ID=3703 . Brother’s name is incorrectly listed as Patrick on the transportation record.

A fellow passenger on the Waverley was Sarah McTigue, aged 30 from Mayo, Ireland.

As Mary’s orphan school record shows, she was released to her mother at the age of about 7. The family was reunited as her parents completed their sentences. John McKinley became a constable and was stationed in Kempton.

Kempton in the morning fog.

Also in the region were two other convicts – Peter Flynn who was transported for manslaughter, and John Gorman who was a former soldier, transported for insubordination.

Peter Flynn and Sarah McTigue were married at Oatlands in 1850, while the new church was still under construction. The McKinley family probably attended that wedding. In 1850, Mary was aged about 8.

Mary must have grown up with John Reading around. He was a quiet man, not much of a talker apparently. He was 5 foot 7 with dark brown hair and blue eyes. I don’t have a description of Mary in her prime.

A mere 8 years later at the age of 17 – which can’t have been true, she was actually 16 or perhaps even 15 – Mary and 38 year old John Reading were married. The witnesses were Sarah Flynn (formerly McTigue) who made the crossing with Mary and her mother, and John Gorman, friend of John’s and a fellow soldier-convict.

John Reddan is recorded as John Reading and perhaps he was a farmer. Mary Ann McKinley is recorded as Mary Ann McGinty and she clearly presented herself well. ‘Lady’ is an unexpected status.

From all accounts, it was a very happy marriage. John committed one offense about twenty years later – after five days he closed the gate on a stray cow who had wandered into his paddock and accidentally branded the cow’s calf along with his own. Several character witnesses reported that he was a law-abiding man who participated in community life.

House in Oatlands

Twelve children were born to John and Mary. Their son Thomas was my great grandfather.

John died in 1893 in Kempton, aged 73. Mary moved in with her son Thomas and his wife.

My grandmother’s eldest sister remembered Mary McKinley who was her own grandmother and used to babysit her. She said she was a very old lady in a dark coloured dress who liked to talk.

Mary Ann Reading died on 13 Aug 1919 and was buried at St Peter’s Catholic Church Cemetery in Kempton. No headstone remains.

Mary’s death entry in the family bible (confusing bit of previous entry removed)