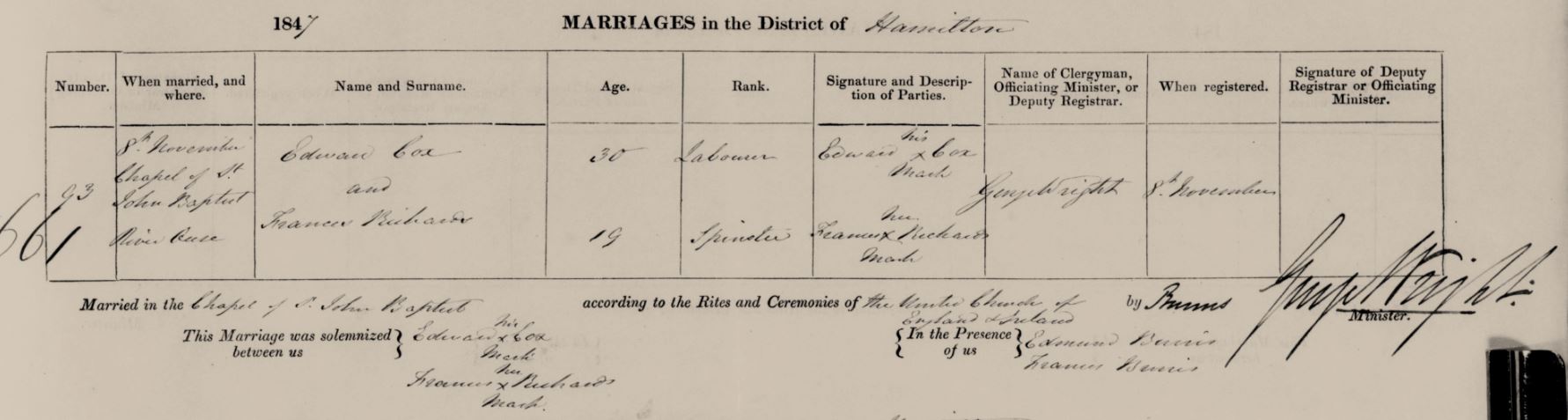

Link to Part One Link to Part Three

Weather report for 17 March 1896, London (1):

Throughout England and Ireland there was a boisterous, squally wind, blowing strongly in many localities … Early in the night temperature fell under 40deg (4.5 Celsius) over about half the country … but it rose quickly before morning, all but a few northern stations standing at from 45 deg to 53 deg (7-11.5 C) at 8am. In the course of the forenoon the cyclonic core moved across Scotland at rather a brisk pace, and shortly after noon it was out on the North Sea off the Aberdeenshire coast, the barometer going up steadily at all our home stations. The wind was shifting into west and north west in the afternoon … the sea off Holyhead and in the Straits of Dover was running high. Squally weather reported all round … temperatures from 51 deg to 53 deg (10-11 C) at 2pm.

The increasing wind reached London early in the night, and up to about midday yesterday the south-west breeze blew hard in frequent squalls, which at times attained the force of a moderate or fresh gale.

This reported ‘breeze’ brought down cranes and pylons, sunk two ships and destroyed the Coroner’s Court in the Police House in Liverpool. In Scotland and Ireland, the damage was much greater. It was officially named a cyclone once it reached St George’s Strait.

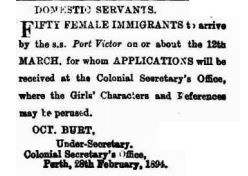

In the middle of the storms, Flo and Allie had packed, headed for their boarding point and joined 46 other girls for the adventure of their lives.

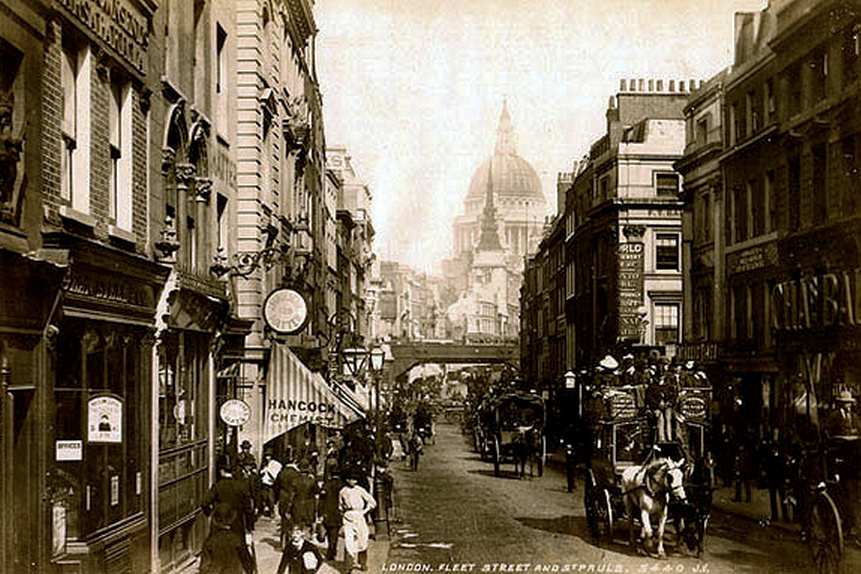

The arrangement was that the girls were to meet the day before sailing and all sleep at a hostel booked for the purpose near the wharf. (2) . Some were coming from British country regions, a few from Scotland and others from Ireland.

Another paper reported (3)

The emigrants are housed temporarily on their way through London … and often clothed more comfortably with … half-worn garments contributed.

So Flo and Allie would have met their fellow passengers on 16 March 1896. Even now, their travels were not confirmed. There was a medical check undertaken upon arrival. Some girls were rejected. A couple withdrew. Flo and Allie were deemed ‘satisfactory’ and were also up to date with their vaccinations. Presumably after passing the medical inspection they were allocated their quarters for the night.

In the morning they would, I expect, have traveled together to the wharf in a group.

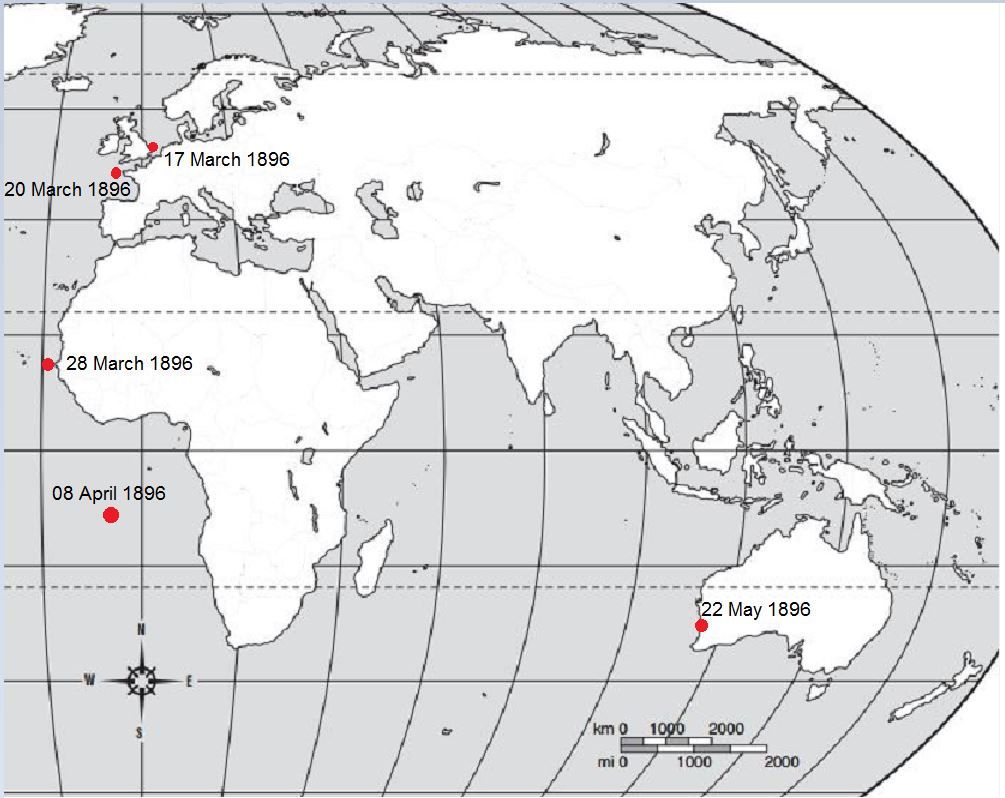

The ship sailed without incident and the passing of the Port Phillip steamer at Ushant was reported on 20 March 1896.(4)

The papers of the UBWEA are held by the Women’s Library Archive at the London School of Economics and are not digitized. From various oral histories it is known that the girls received organized training while on board. Miss Monk inspected their needlework, their diction, their posture and their cleanliness. She ensured they knew how to wear their uniform and she ensured they were in good health.

Ocean near Australia

From the diary of ship’s doctor Dr Walter Bridgeford (5):

The Port Phillip left Gravesend on St. Patrick’s Day carrying 48 single girls, migrants for the Government of Western Australia, the matron in charge being Miss Monk . . . . Eleven days later, on March 28th, sighted San Antonio (Cape de Verde Islands), and on the same day entered the Bay of Porte Grande, St. Vincent. Porte Grande is about two miles wide at the entrance and is the largest harbour in the Cape de Verde Islands. It is well sheltered under high mountains and is the termination of a central valley running throughout the island between two chains of mountains. The anchorage is a good one and sufficiently large, it is said, to accommodate 200 large ships. The general aspect of St. Vincent from the Bay is mountainous, with high peaks. It wears a barren and desolate appearance, the volanic fires of a past age together with the scorching heat of a tropical sun having, in most places, rendered the soil unfit for cultivation.

There are two small churches-one Protestant and the other Roman Catholic, the former being at the time of our visit without a minister ; a very sandy cricket ground ; the usual public square, which is lighted at night and wherein a band plays regularly ; water-works, which are situated in the centre of the town ; the Governor’s palace ; and the barracks. The place is scorchingly hot-92 deg. Fahr. in the shade as I write and there is no vegetation beyond a few trees which have been planted in the streets. The houses occupied by the employees of the coaling companies and the cable telegraph staffs are large and commodious, well lighted and ventilated, and include the luxury of wood billiard rooms.

The natives are black in colour, but black of various degrees of density. Their houses are wretched hovels, a wooden shutter serving the purpose of a window, and dirty sand doing duty for a floor. There are a few stores on the island, an apothecary’s shop, and a building which by courtesy only is designated an hospital. (The water supply is good. Provisions are imported from neighbouring islands ; but notwithstanding the absence of herbage, goats manage to live. We only remained about 20 hours, and left on the 29th to pursue our voyage with 260 tons of coal on deck

Flo and Allie may have had a chance to go ashore. If not, they would have viewed the place from their ship. I also wonder if the blatant racism upset them, if they were close enough to notice the different living conditions of the Indigenous people versus the colonials.

Cape de Verde Islands today. By Ingo Wölbern (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/43/Furna_Cape_Verde.jpg

All went smoothly until 8th April 1896 off the coast of St Helena.

From Bridgeford’s diary:

On April 8th, however, we learned that the ship was on fire. About a quarter-past 9 at night, and when we were about four miles N.W. of St. Helena, smoke was reported to be coming through the tunnel into the engine-room. The hose was at once got ready.

Meantime the emigrants’ steward reported smoke in the girls’ quarters in abundance. This was in the No. 3 hatch, next to the engine-room. The night being fine and clear, the girls were all ordered on to the poop.

I looked in the baggage room with the second officer and steward, but only to find it full of smoke. Steam and water were at once played into the hold, which was battened down. Several steam jets were played inside from the engine-room, and water was poured on outside.

The heat of the deck was intense. Only one box and portmanteau were recovered, the smoke being too dense to allow of more being brought up. We put the girls up in the saloon for the night, where they were fairly comfortable, which was as much as could be expected, considering the saloon is intended to accommodate 12 passengers only, whereas we had 53. As the fire was still raging two boats were lowered in readiness for emergencies, and the captain bore up for St Helena, which we reached at 2 o’clock the following morning.

Most of the girls were apparently in their nightclothes and were not allowed back to their sleeping quarters. Another report mentions how Miss Monk was a tower of strength at this time, leading the girls in a prayer and locating blankets for them to use while they waited. Miss Monk also arranged for tea and sandwiches shortly before dawn which was apparently very welcome.(6)

St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. Andrew Neaum [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons. No changes made. Attribution required. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASt-Helena-Jamestown.jpg

Bridgeford’s diary again:

Steam and water had been kept playing in the hold all night. The girls behaved splendidly throughout, there being no sign of panic. At 7 o’olook the harbour master came on board, and as the fire was still burning, it was deemed advisable to house the emigrsnts on shore. His Excellency the Acting Governor, Mr. Sterndale, very kindly placed the mess-house, formerly occupied by the officers of the garrison, at our disposal. This is a commodious building, situated in the main street, with verandahs on each floor, and only ten minutes’ walk from the landing steps of the wharf.

We utilised two large rooms on the first floor. Behind was an extensive yard, also kitchen, bath, and outhouses, and a plentiful supply of water. Mattresses, blankets, mugs, plates, lockers, and cooking utensils were lent by the Colonial Government military authorities, Emigration Department, and also by the manager of the (Miss Werton’s) Sailors’ Rest.

At 3 o’clock in the afternoon the hatchway of the streamer was opened, and the baggage, which was then hoisted on deck, presented a lamentable appearance. Some boxes were still on fire. Others, when opened, showed their contents charred and destroyed, while many were missing altogether.

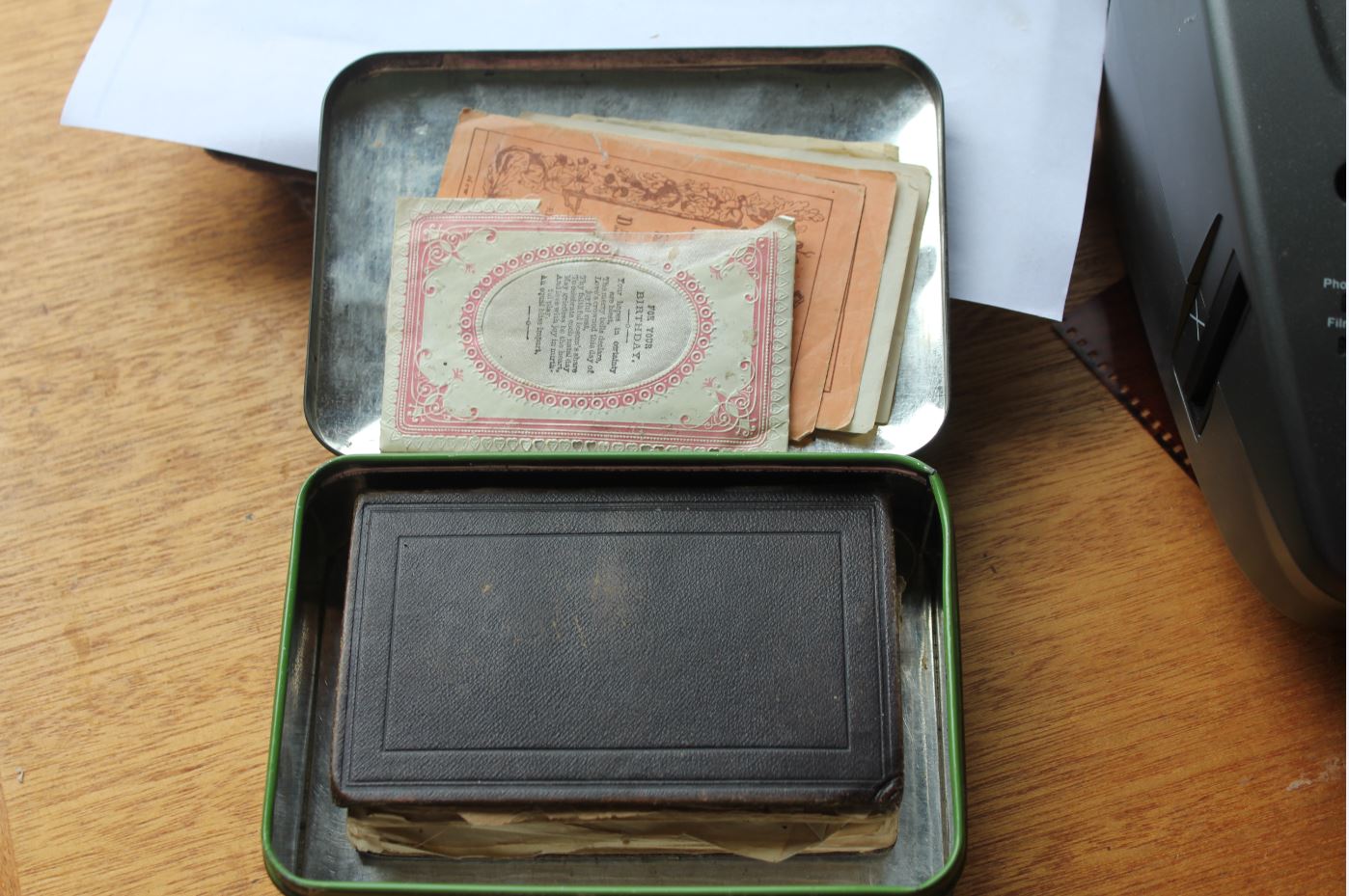

The loss to the girls was considerable, many of them having disposed of their little all to provide themselves with a good outfit, now found themselves landed at St Helena with only the clothes they stood up in. Besides, all possessed souvenirs of some kind from family or friends which can never be replaced.

The emigrants were landed by half-past 4 p.m. in small boats, the steam tug in the harbour not being licensed to carry passengers. The landing here is somewhat difficult. However, all the girls got ashore safely and without mishap, but looking all the worse for their night of terror, want of sleep and loss of clothes.

The fire in ship was still burning next day when Lloyd’s surveyors went on board. During our stay on the island His Excellency the Acting-Governor and Mrs. Sterndale, and also the wife of the Governor (Mrs Grey-Wilson), called on several occasions to see the emigrants. Many other ladies also called, not a few of them sending fruit and flowers in abundance, while invitations to ” spend the day ” at their houses on the hills were numerous. It was, of course, impossible to accept all invitations, owing, in some cases, to the distance involved and the difficulty of transport, to say nothing of the heat.

Apparently the ladies of the town donated some clothing to the girls, but there were not many items of spare clothing on the island. More clothes were donated by incoming ships over the next fortnight.

Flo and Allie must have told their descendants about this unexpected fortnight on a tropical island, but as far as I know the stories have not survived.

Back to Bridgeford’s diary:

One day half the emigrants visited Longwood Farm, at the invitation of Miss Deason, where they were most hospitably entertained. They also visited Napoleon’s tomb, which lies en route from Jamestown to Longwood. The same day the remainder were entertained by Mr. Homagee, the magistrate, at tea and tennis -a sort of garden party. The advent of so many white girls on the island caused some little commotion so far as the local ” Tommy Atkins ” was concerned, the red-haired girls being particularly

cynosured by the natives. In the castle there resides the oldest inhabitant, a Miss Bagley, the housekeeper, who, being bedridden for the last five years, is relieved of her duties by a niece … the old lady requested the matron to send the girls to see her. Miss Bagley has reached the age of 90 years, and had never before seen red hair. Having had a goad look at it, she was delighted, and pronounced it pretty. She also asked her visitors for a “lock,” which request was readily acceded to.

A visit to the Colonial Hospital was most interesting. Miss Williams, the lady superintendent, resided at Kimberley some years ago, and so had many stories to tell of South África, of which the world is now talking so much.

On April 12 many of the girls attended the communion service at the church, which service was conducted by the Lord Bishop of St. Helena, Dr. Welby, a very aged prelate who has seen 86 summers, but who is still active. The same morning the Bishop held a

service in the moss house.

Every evening between 7 and 9 o’olock crowds assembled outside the mess house to listen to the girls singing and the town being usually very quiet at night, all the officials and principal merchants living on the hills three or four miles away, this proved a pleasant break in the monotony of the lives of those compelled to remain in town.

There is a Salvation Army corps at St. Helena, as there is everywhere, and the soldiers gave us from time to time the benefit of their big drum.

On the 17th, the matron and girls were the guests of the Governor and Mrs. Sterndale at their residence, the Plantation, three miles from Jamestown and 1,800ft. above the sea level. The Governor seat an ambulance waggon which seated six girls, his pair-horsed carriage to seat four, and the magistrate, Mr. Homagee, his one-horsed carriage to seat two, and with the means of locomotion thus provided, the girls walked and rode alternately from the coast to the Acting-Governor’s residence, where they arrived at 11.30 a.m. After inspecting the grounds they attended service at the ” Cathedral,” a small church with numerous mural tablets in memory of varions officers, civil servants and other inhabitants of note who have died on the Island. The rest of the day was spent in eating and drinking and various forms of amusement organised for the occasion, a number of visitors from Jamestown sharing the Acting-Governor’s hospitality.

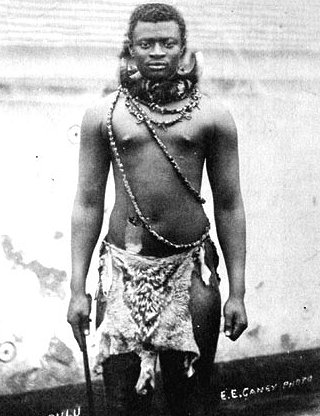

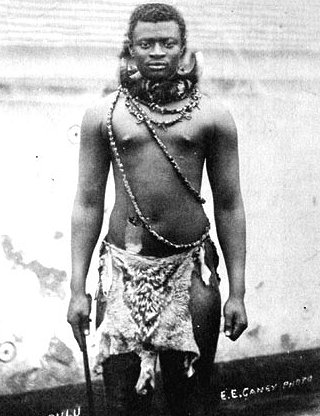

Photo of Dinizulu with wood badge beads during Zulu civil war. E. E. Caney Photo – Retrieved from http://www.pinetreeweb.com/bp-dinizulu.htm. Original Photo from the collection of the Killie Campbell Museum, Durban, South Africa.

Bridgeford’s diary continues:

The party returned to Jamestown by 7.20 p.m., escorted by the Acting-Governor and his orderly. On April 20 the matron and one sub-matron and eight girls visited the Zulus at Maldives, a pretty house situated in the valley above the Colonial Hospital, and standing in a spacious garden loaded with tropical plants and flowers. These Zulus were sent here as prisoners of war seven years ago, after a rising in Zululand. There are three princes or chiefs. Dinizulu is a son of Cetchwayo, a fine blackman about 30 years of age, of a somewhat semetic cast of features. He arrived here a naked savage, but now dresses in the height of fashion, dances, sings, plays the piano, and speaks English fairly well. Ndabuko is a brother of Cetchwayo. about 60 years of age, and weighing about 22 stone.

He will not learn English, and is very morose. Tebangani ia a step.brother to Cetchwayo, smaller in stature, about 55 years of age, somewhat decrepit, though lively and vivacious in con-versation. He seaks English fairly, but not so well as Dinizulu. These dusky prisoners have with them their wives and families, servants, and interpreter. They were condemned to twelve years’ exile. On the island, however, they live in perfect freedom, but are not allowed to go on board ship without the Governor’s permission. They are in charge of a guardian sent by the Natal Government, but are under the direct orders of the Governor. They received the visitors most courteously. Dinizulu, the least bashful of the three, being particularly attentive, played and sang and regaled all with ” nectar,” a drink made from fruit, and also gave his autograph to each one. An agitation for the release of the Zulus is on foot, led by Miss Colenso, who was shortly expected on the Island, but is not likely to find favour with the Natal Government.

On April 22 we took our departure from St. Helena, all of us extremely grateful to the authorities, from the Acting Governor downwards, for the generous and kindly hospitality which was afforded us during our compulsory sojourn in that delightful island, historically famous for its Napeolonic associations.

The SS Port Phillip finally reached Fremantle on 22 May 1896. The girls disembarked on Fremantle’s old mile-long jetty and made their way to the accommodation waiting for them.

Flo and Allie were now ready to find employment in their new colony.

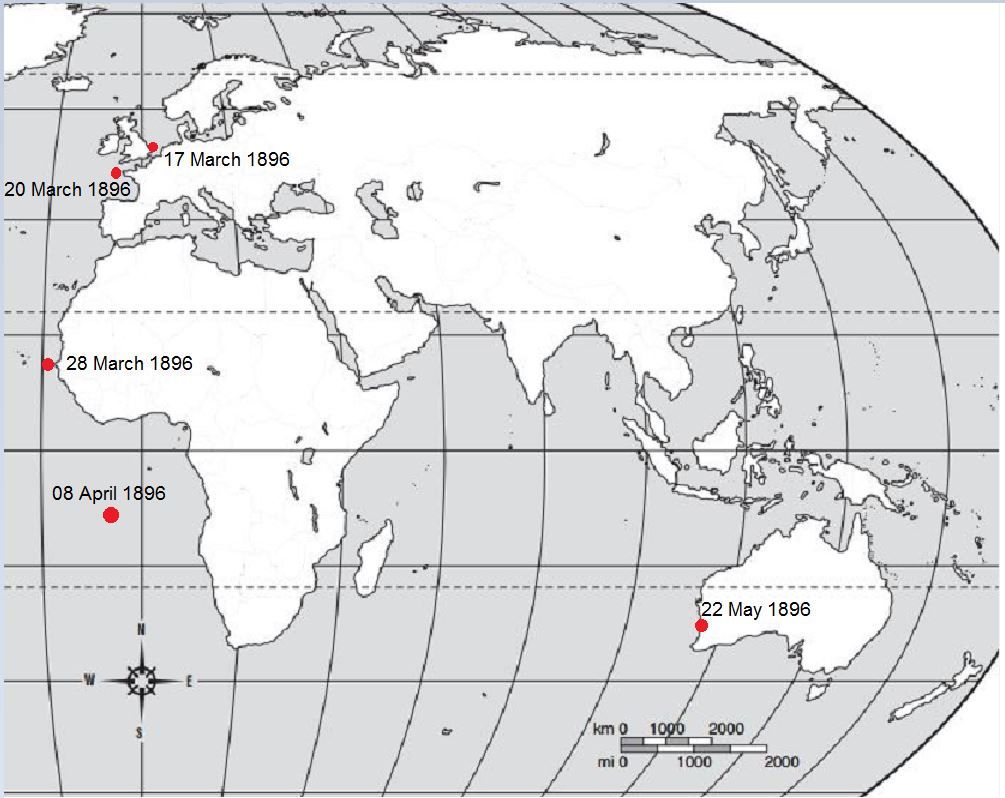

Alice’s journey to Australia 17 March 1896 – 22 May 1896

Appendix item – newspaper account of the arrival of the ‘Port Philip’ at Fremantle:

ARRIVAL OF THE S S. PORT PHILLIP

THE FIRE ON BOARD.

The steamer Port Phillip, of the well known and popular ” Port ” line of ocean traders, put in an appearance at Fremantle at 7 o’clock yesterday morning. The voyage from London had been an eventful one, the terrible ordeal of a fire on board having had to be faced and mastered.

A departure was made from London on 17th March, and very fair steaming was made to St. Vincent, where a stay of a few hours was made for coaling. The passenger list of the steamer consisted principally of 48 emigrant girls, and the comfort of all was undisturbed until the 8th April.

Shortly after 9 o’clock on the morning of that day the second engineer reported that smoke was coming from the vicinity of No. 3 hold, abaft the engine-room. Inspection showed that the tunnel was full of smoke, and the engineers endeavoured to find the cause of the apparent fire. The first engineer, after a gallant attempt to travel along tbe tunnel, had to desist, and his removal on deck was necessitated owing to the effect which the smoke and fumes had upon him. The second engineer and chief officer following up his efforts were likewise incapacitated, and, as the volume of smoke in that direction was baffling, attention was directed to other parts of the ship. On the next day the fire made itself apparent in the quarters allotted to the emigrants, and a quick clearance of the occupants of that part of the vessel had to be made. Their effects, unfortunately, could not be got out, so rapidly did the fire make progress.

Capt. J. R. Smith, wisely judging that the time for forcible treatment of the danger had arrived, ordered the batch way to be battened down and steam turned into No. 3 hold, with the object of suppressing the fire. This was at a point about four miles north-west of St. Helena. Steam was kept going into the hold for two days altogether, the steamer putting into St. Helena in the meantime. The effect of the steam was immediately beneficial, for the volume of smoke decreased.

It was, however, found that the affects of the emigrant girls had been heated and charred so to such an extent as to render them useless. The result was that many of the girls had to land on St. Helena without full clothing. Here, thanks to the good offices of the inhabitants and the Acting Governor, Mr. Stanley, they were well provided for, while the doctor of the ship, Mr. Walter Bridgeford, Capt. Smith, and the matron, Miss Monk, were assiduously successful in relieving the distress of all the sufferers.

The discipline on board throughout the trying circumstances of this part of the voyage is spoken of by all the passengers in terms of the highest praise, and Capt. Smith and his officers, together with Mr. Bridgeford, were heartily cheered by the girls as they left the steamer yesterday at Fremantle. The delay at St. Helena extended over 14 days. For the remainder of the voyage the weather was favourable. (7)

(1) Morning Post 17 March 1896 ‘The Stormy Weather’ p.4

(2) Willesden Chronicle 14 May 1897 Advertisements p.5

(3) Woman’s Signal 18 July 1895 ‘What Women Are Doing’ p.5

(4) Leeds Mercury 20 March 1896 ‘Mail and Shipping News’ p.7

(5) “VOYAGE OF THE PORT PHILLIP.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 26 May 1896: 7. Web. 3 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3090849>.

(6) Woman’s Signal July 1897 ‘Annual report of the UBWEA’ p.4

(7) “ARRIVAL OF THE S. S. PORT PHILLIP.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 23 May 1896: 6. Web. 3 Apr 2018 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3090571>.

SRO of Western Australia; Chronological list of Inwards passengers from overseas to Freemantle 1880 – 1898; Accession: 503; Roll: 212