East Harptree in Somerset England, the ancestral region of the Burletons and Wookeys

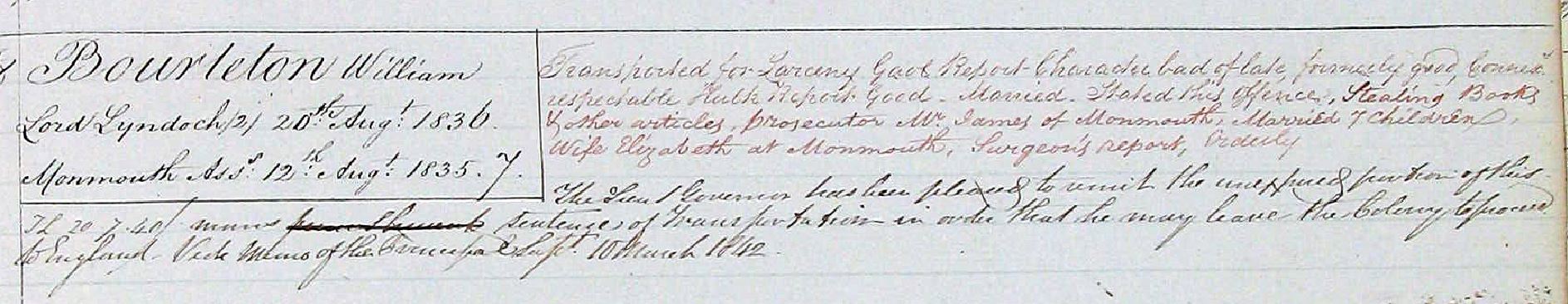

William strikes me as a sort of tragic character. He could have been the most illustrious of his family. I’m willing to bet that was his intention. His ambitions might have been realized had he lived just forty years earlier before the industrial revolution really kicked off. Large scale manufacture swept the rug from under William’s feet just as he risked all of his family’s wealth in one massive business speculation. With the failure of that business, he lost almost everything – his wealth, his home, the respect of his neighbours, the support of his extended family and we can’t know for sure, but he probably also lost the trust of his immediate family, his wife and children.

It was going to happen to the family anyway – the industrial revolution was very tough on provincial yeomen who were not placed to take on the hard nosed role of factory or franchise owner. There wasn’t much call for that in the isolated central regions of Somerset in England. The outside world was still passing these people by. They were a step back in time, living by rules which had ceased to apply in most of England by the turn of the 19th century. But though with hindsight we know that it was probably going to happen – at the time, it all looked like the fault of William Burleton, eldest son and heir to a moderate but sufficient livelihood built up by the generations before him.

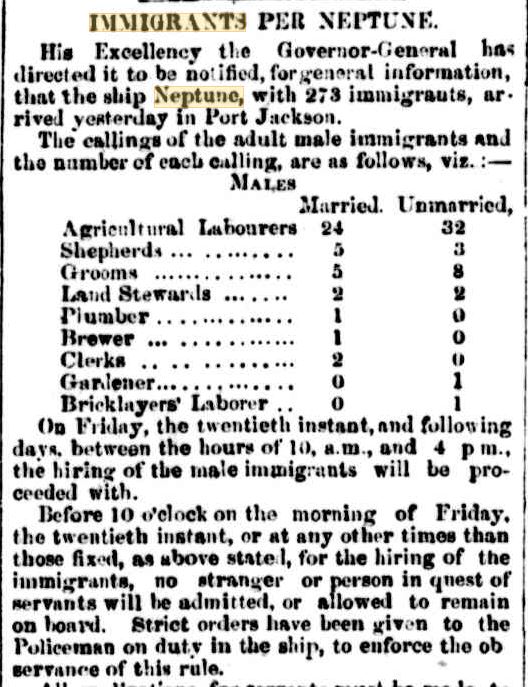

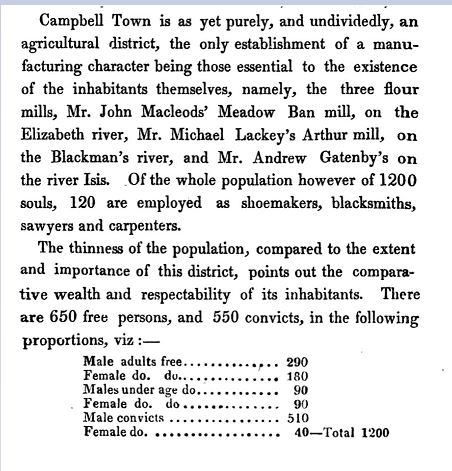

Flour Mill Equipment

William was baptised on 25 Dec 1783 at East Harptree, Somersetshire, the eldest known son of John Burleton and Sarah Butler. He had two elder sisters, Elizabeth and Ann. There is room for another child between the two girls but no more records have been found.

Both of his parents came from yeomen families. John Burleton’s father was a Burleton of Motcombe, Dorset, a family who had owned land there for generations. John’s wife Sarah was a Butler from Witham Friary. They and their relatives were local magistrates, church wardens and large scale benefactors of local charities. Their credit was good, their standing was very good. William was born into a world of advantage.

I have found no records regarding their education, but the children all reached adulthood with the ability to read and do accounts, even the girls which was not always the case in those years. After William came Robert, Joseph, Sarah and John. (There is a slight discrepancy in John’s records, he may have been older).

He reached adulthood without entering into any official record and became a miller and dealer in meal.

Church of St Margaret at Hinton Blewett By Rodw [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons . No changes made.

William married Elizabeth Dudden at St Margaret’s in Hinton Blewitt, Somerset on 18th June 1807.

For years, I had the wrong Elizabeth Dudden. There were two and they were second cousins. I thought he had married the daughter of Parsons Dudden who was born in 1788. It turns out he married the daughter of George Dudden who was born in 1784.

Which is the first indication, really, that William was headstrong and that he lacked the conservative practicality of his family.

It’s the reason I hit on the wrong Elizabeth. The Duddens were yeomen of the past. By 1800 most of them were struggling labourers but with a few lines of descent which held on to small properties and local prestige. Parsons Dudden was one of those. George Dudden was not. It made perfect economic sense that a Burleton would marry a daughter of Parsons Dudden. But he married the daughter of George.

Chew Magna, the home of Elizabeth Dudden’s mother Mary. By Robert Cutts from Bristol, England, UK (St Andrew’s Church, Chew Magna, Somerset) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Not that I wish to denigrate George and his family. They were honest hardworking folk as far as I can tell. But they were landless labourers and Elizabeth made a startlingly good marriage, in the Jane Austin sense. I have a feeling she must have been very pretty.

The comparison to the Bennett girls of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ can be taken further, though this family was in a different social sphere entirely. Elizabeth Dudden was the daughter of George Dudden and Mary Harvey. George was from the less successful branch of a respectable Dudden family – admittedly a surname which only had meaning in the highlands of Somerset – while Mary Harvey was a girl from a labouring family. At the marriage of George and Mary, he signed the register while she marked with an ‘X’. What she was able to teach her daughter about good household management and the dull, self-important world of respectable yeomanry is uncertain.

So Mary had made a good marriage by uniting herself with George Dudden, and Elizabeth then made a good marriage by uniting with William Burleton – which brings us back to William himself.

The marriage record is in the name of William Burlington.

MARRIAGE EAST HARPTREE:

William Burlington and Elizabeth Dudden, both of this parish, were married in this Church by Banns this Eighteenth day of June in the Year One Thousand Eight Hundred and Seven by me, Hugh Lewis, Curate.

This marriage was solemnized between Us :

William Burleton (signed his name as Burleton)

Elizabeth Dudden (signed her name)

In the presence of Samuel Hand and Hester Lewis.

They became the parents of a large family:

William 19 Apr 1809 Hinton Blewett

Eliza 01 Jul 1810 Hinton Blewett

Sarah 17 May 1812 Litton

Francis 31 Jul 1814 Litton

Elizabeth 30 May 1816 Litton

William 19 Jul 1818 Chewton Mendip

George 6 Jan 1820 Chewton Mendip

John 4 Oct 1821 Chewton Mendip

Robert 1 Dec 1823 Chewton Mendip

Eliza 13 Sep 1824 Chewton Mendip

It was in Litton that William made the mistake which changed the whole course of his life.

On his own land, William built a brand new flour mill, putting himself into debt with the expectation that the business would prosper and enable him to pay back the money. He built the finest mill that he could, filled with new equipment. Litton was very proud of it.

Litton in Somerset

With the benefit of hindsight, the first indication of financial trouble appeared in 1815 with a notice in the Bath Chronicle (1):

SOMERSET

TO be LET, in the parish of LITTON near Chewton-Mendip, for one year, five or seven and entered upon at Lady Day next, a New-built and Well-accustomed WATER GRIST-MILL, working two pair of stones together, adjoining with a neat Dwelling-house, Bake-house, two Gardens, large Orchard, barns, stables, pig-houses, and all other offices, suitable for any respectable person who wishes to enter into the Meal and Baking business – for a view of the premises apply to Mr Wm Burleton, the proprietor, of Litton aforesaid.

The notice reappeared in the Bath chronicle in September 1816 in almost identical words.

Another notice appeared in the Bristol Mirror in 1820:

TO MILLERS AND BAKERS

TO be SOLD by Private Contract, with immediate possession, a newly-erected FLOUR MILL, called Litton Mill, working two pair of Stones; with a good substantial DWELLING HOUSE, Bake-house, Barn, Stable, and other Outhouses, Gardens and Orchard adjoining; situate at LITTON near Chewton-Mendip, in the county of Somerset; distant from Wells 6 miles, Shepton-Mallet 7 miles, and Bristol 13 miles.

The above Premises are part of the Manor of Litton, and held by Copy of Court Toll for three young healthy lives.

For further particulars, and to treat for the purchase, apply to Mr WILLIAM BURLETON, of Chewton-Mendip, or to Mr DOWLING, Solicitor, Chew-Magna.

N.B. If the above Premises are not sold before the 1st of May, the same will be then to be Let. (2)

In 1823, William’s eldest daughter Eliza died at the age of thirteen. Her cause of death is not known. It must have added to an already troubled time for the family.

Scene of family from ‘The Fairchild Family’ by Mrs Sherwood, 1826 edition.

A further notice in the Bristol Mirror in 1824 for the sale of a property belonging to William Burleton.

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION by SAMUEL OLIVER,

On MONDAY NEXT, the 12th day of January, at the Mitre Inn, WELLS, at five o’clock in the afternoon, (unless in the meantime disposed of by Private Contract).

A COMPACT FARM,consisting of Five Closes of Arable and Pasture Land, adjoining each other, containing together 105 Acres (more or less), situate on MENDIP, near Green Ore Farm, in the parish of St. Cuthbert, Wells, near the turnpike road, and adjoining lands of John Davis and Edward Tuson, Esquires.

Of the above Premises, 74A. 3R. 24P. are held by lease, under the Bishop of Bath and Wells, for three lives; and the Residue is Freehold.

There is a good Limekiln and an excellent Spring of Water on the Freehold part of the Premises, which abound with Limestone and Stone for Building.

N.B. The above Premises, if not sold, will be to be LET.

For a view of the Premises, apply to Mr. William Burleton, Chewton-Mendip, and for further particulars, and to treat by Private Contract, to Messrs DOWLING AND MARSHALL, solicitors, Chew-Magna. (3)

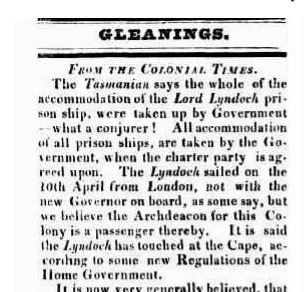

It all came to a head in 1826. A suspicion of mine is that William’s creditors were assuming that he would inherit from the estate of his very elderly father. John Burleton was almost forty at the time of William’s birth. Now he was about to turn eighty and was probably ailing. But at John’s death in November 1825, his property – Eastwood in East Harptree – was left to his second son Robert, skipping over the elder William.

The family probably knew more about William’s character than we can deduce today through the records. The creditors waited no longer. It was game over for William Burleton.

FROM THE LONDON GAZETTE

BANKRUPTS

W. Burleton, Litton, Somersetshire, mealman (4)

Landscape around Monmouthshire. Public Domain photograph.

There was something of a rift within the family from this point. Whether it was William removing himself from them or vice versa is unclear. William’s brother Robert – a highly responsible, sensible, solid chip off the old block if ever there was one – rendered assistance to the family by taking Joseph and Francis under his employ. Looking at the generations ahead, this was something we can be very grateful for. But it probably didn’t feel like much to William.

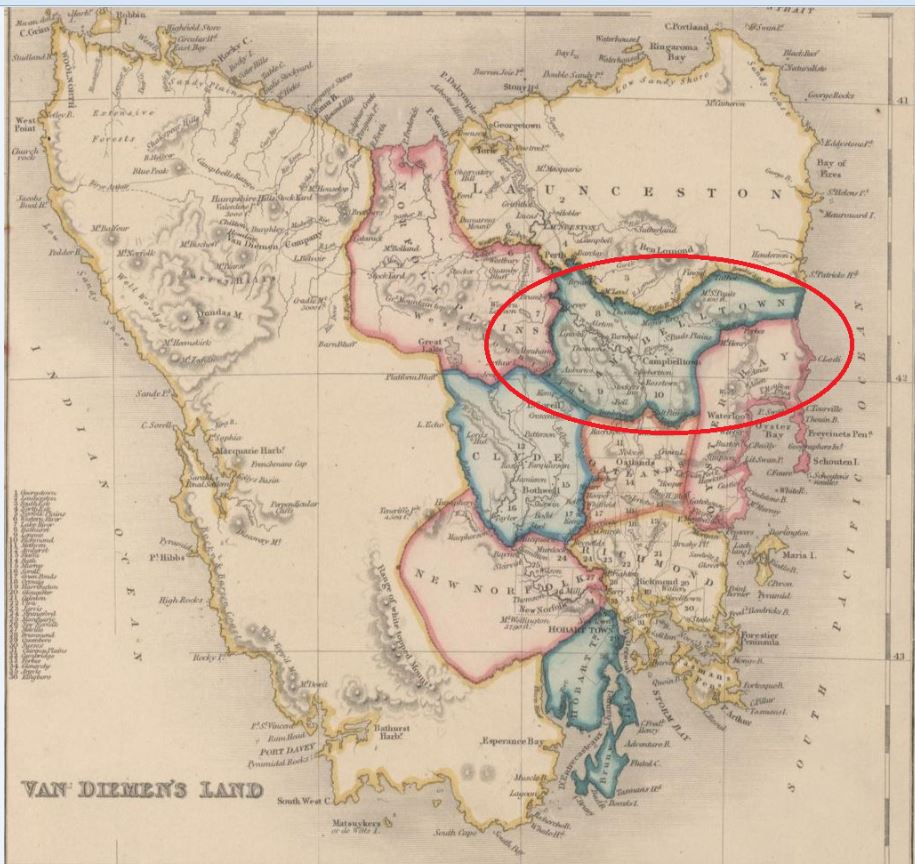

William and the rest of his family moved to Monmouthshire. Two children – William and Eliza – were deceased. Joseph and Francis stayed in Somerset. The other seven went to Monmouthshire with their parents.

Maybe there was family there that I haven’t discovered. Maybe they just got the hell out of the home town with its pity and recriminations and sideways glances and memories. Perhaps Monmouthshire seemed like the place for a new beginning where nobody knew them. Perhaps it was brother Robert’s doing.

William took employment at a country mill, working for a Mr John James. It was a chance for a new start – not easy for a man in his forties who until now had had all the luxuries and conveniences that he could desire.

But at least he had a fresh beginning and he still had his family. Perhaps it wasn’t game over after all.

Story of William continues here.

-

- ‘SOMERSET’,Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 23 November 1815 p.3

-

- TO MILLERS AND BAKERS, The Bristol Mirror 15 Apr 1820 p.1

- ‘TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION’, The Bristol Mirror 10 January 1824 p.1

- ‘BANKRUPTS FROM THE LONDON GAZETTE’, The Caledonian Mercury 25 Sep 1826, p6