House outside the rural township of National Park Tasmania, the residence of a direct ancestor. A good indication of lifestyle and environment in this region. Photograph circa 1944.

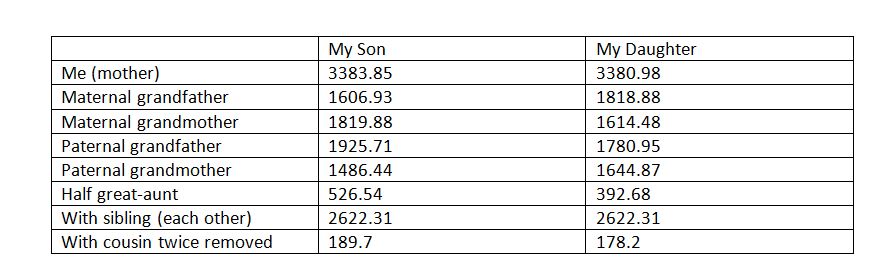

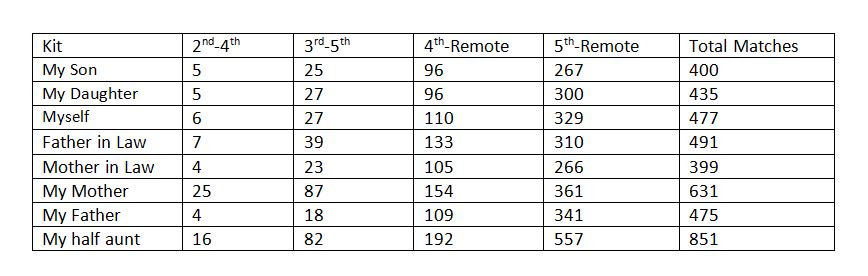

Every so often in family tree research, we hit rough patches. Perhaps a war destroyed the records, or mass emigration changed surnames beyond recognition. Perhaps a desire for respectability caused records to be falsified. Sometimes we recognise this, sometimes we don’t. I’ve just discovered such a patch in my own research, highlighted by the Family Finder DNA test.

I’m still looking deep into the cold woodlands of inner Van Diemen’s Land. It was difficult terrain as I’ve said before, hilly and heavily forested without roads or any type of services. Babies were born out here with only the family around and were never registered or baptised. If anyone died, there was a chance they’d never make it onto an official record at all. You can find death registrations ten to thirty years after the event, required for a widow to receive the newly introduced age pension, or for a next of kin to receive a deceased soldier’s belongings. It is very hard to know who was out here at any particular time.

I find it interesting that of the four family branches in my research, three of them had ancestors out here with no apparent connection between. Perhaps more people moved through this area than it seemed.

Certainly, there were churches and pubs, but these were in the towns and I’m trying to track the country folk. The best clues come from inquests and other court cases where they were called as witnesses.

An indication of the isolation of these communities. Lane’s Tier was a rural locality in the highlands of Tasmania near Hamilton. Article from Trove “IN CASH OR KIND?.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954) 7 Apr 1873: 2. Web. 21 Mar 2015 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8922227>

In my last blog post I looked at the Daley family who lived in the Hamilton region. Owen Daley married Susan Triffitt in 1859 when she was already eight months pregnant with Isaac. Isaac then married his first cousin Maria Triffitt in 1878 when her twins were already one year old. The twins were named Sidney and Fleetwood. Sidney Daley then married Fannie Elizabeth Rawlinson in Ouse in 1899 and their daughter Evelyn was our line.

Only I somehow never noticed that Evelyn was four years old at the time of that marriage. The chances are rather slim that Sidney Daley was actually her father. There’s probably no Daley DNA in our family at all. There’s also a very good chance that this is the pathway of the unexpected X Match between my father-in-law and his known third cousin. Evelyn Daley is in my father-in-law’s direct maternal line.

Fannie Elizabeth Rawlinson is a favourite of mine. She was called ‘Granny’ by her grandchildren, one of whom was my father in law’s mother. They remembered her as a happy lady who gave them sweets and made a house feel like a home. In the only photograph of her that I have seen, she is smiling and the smile looks habitual. Her own education was minimal but she could read and write. In later years she moved into the suburbs of Hobart. She passed away in 1953.

Headstone of Fannie (Fanny) Elizabeth Daley displayed with permission from Gravesites of Tasmania http://gravesoftas.com.au/home%20page.htm

The Rawlinson family has always interested me, but I still don’t quite understand them. They were intelligent and enterprising but never quite got ahead.

The earliest I have ascertained with certainty is one Peter Rawlinson, born in Stockport, Cheshire, England in early 1811. He was the base born son of Alice Rawlinson and I don’t know what happened to her. Since Peter was born in Cheshire and was still there for the 1841 census, there’s a good chance his mother stayed too. Maybe she married, or maybe passed away.

In 1831 at the age of twenty, Peter married Frances Oldham who was aged about fifteen. Peter was a weaver in his early married days. There was undoubtedly a child born in 1832 who must have died. James was born in 1834 and Edwin in 1837. Frances was next in 1838 and she was aged three in the 1841 census. Alice was born in about 1844, after which Frances Oldham passed away. At some time young Frances Rawlinson also died. In the 1851 census Peter Rawlinson was a tripe setter with his own store, employing his sons James and Edwin. Alice was a scholar aged six.

Peter hired a girl to care for Alice, and that girl was Frances (Fanny) Eyles from Bath in Gloucestershire. At the time of the 1851 census, Fanny Eyles was aged 24 while Peter Rawlinson was aged 40.

Fanny Eyles came from an old Bristol family. She was the daughter of John Eyles and Mary Sweet. Mary Sweet’s ancestry has been traced back to the start of parish records on every side. Frances was the fourth child in the family, the second daughter. Her eldest brother was George Sweet Eyles who was nine years her senior.

George Sweet Eyles was a key player in the history of this family.

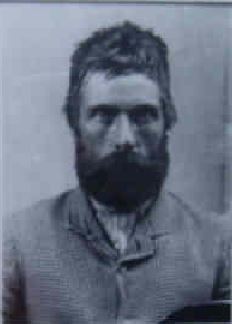

Description of convict George Sweet Eyles CON18-1-19 page 172 via http://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/

He seemed like the black sheep of the family. He was transported for stealing a silver spoon but had been convicted before. In 1835 he was sent to Van Diemen’s Land on the ship ‘Susan’ and in 1843 received a conditional pardon in a repatriation scheme which enabled many enterprising convicts to become settled and successful. George Sweet Eyles was granted land at Ouse, out in the middle of nowhere in the wild lands. Like James Triffitt of my previous blog, he managed to turn a seemingly impossible situation into something quite comfortable. He built his house at Ouse and called it ‘Rocky Marsh’. He became a farmer, he saved his money and he sent back to England to have his family brought out – both his parents, all his siblings and their spouses and children.

Fanny Eyles accepted her brother’s invitation and headed for Australia. With her came Peter Rawlinson and young Alice. James and Edwin stayed in England, being adult men probably with their own lives.

Peter and Fanny travelled as Mr and Mrs Rawlinson but actually did not marry until arrival in Van Diemen’s Land. Their daughter Mary was born around 1854 so was already alive by the time of their marriage.

Marriage registration of Peter Rawlinson and Frances Eyles at St John the Baptist chapel in Ouse, Tasmania, Australia. Peter subtracted a few years from his age while Fanny was more accurate.

I can’t help wondering who really wanted the marriage. Perhaps brother George? He was a strong and tough man, but family was extremely important to him. He expected them to behave but he helped them whenever they needed. Peter does not seem to have been properly committed to Fanny despite the birth of a child.

I have no idea who Sarah Eyles was, the witness to this marriage along with George.

Peter and Fanny Rawlinson only had three children that we know of – Mary born 1855, Peter born 1857 and Elizabeth born 1858. A birth record has not been located for Mary. Peter was born in Victoria and the family had returned to Ouse for the birth of Elizabeth.

The family is very lucky to possess a journal kept by Alice Rawlinson which gives details we could never have learned otherwise. Alice became very close to her stepmother’s brother. He was a forty year old man and she was a fourteen year old girl, but that’s how things went in early Van Diemen’s Land. The ratio of men to women gave every woman a special status in the backwaters, even in the 1850s. They were basically living as one big family anyway, perhaps it was inevitable that the two would get together.

In February 1861, John Foster George Eyles was born to forty one year old George and fifteen year old Alice. There had been no marriage and it seems there never was, unless they travelled interstate for it. Alice was the happiest girl alive. Her two brothers James and Edwin were scandalized and came all the way from England to find out how their father could have allowed such a thing. Their plan was to take Alice back to England and there was a confrontation. Alice refused to go. In the end the family seems to have split up. James and Edwin left, their father Peter and their brother Peter seem to have gone with them. Fanny can be found in Ouse a couple of years later with daughters Mary and Elizabeth. She moved in with her brother and her stepdaughter and became their housekeeper.

Peter Rawlinson junior stayed in Victoria, marrying Isabella Duckett in 1890. Isabella was aged 35 and only two children have been located. Peter Rawlinson Senior vanished, but a death record in Cheshire in the 1870s may be his.

“THE MERCURY.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954) 15 Apr 1885: 2. Web. 21 Mar 2015 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article9103480>.

Mary Rawlinson married Henry Stump, a rather wealthy merchant from Hobart. They settled in Hobart and raised a large family. Elizabeth met Alfred Morling, the younger son of another wealthy merchant and they had two children, Albert and our Fannie Elizabeth, but he would not marry her. Elizabeth sought redress in court and Alfred was forced on several occasions to pay maintenance.

Elizabeth then met Henry Dawson, a carter, and moved in with him. Two daughters were born to them, one of whom died young. Unfortunately Henry also died, leaving Elizabeth a single mother now with three young ones. Finally she found Albert Triffitt, a man she had probably known for years. Albert not only married her, but stayed alive long enough for many more children to be born.

Fannie Elizabeth Rawlinson, daughter of Alfred Morling and Elizabeth Rawlinson, was born in Ouse and grew up on the property at Rocky Marsh until her mother married Albert Triffitt. For those who read my last blog entry, Albert Triffitt was a son of Edward Triffitt and Mary Taylor. Edward Triffitt was a son of Thomas Triffitt and Mary Scattergood, and so was the brother of Susan Triffitt (wife of Owen Daley) and also the brother of John Frederick Triffitt, the father of Maria Triffitt who married Isaac Daley. Some people – probably the wise ones – don’t even try to get the family structure correct. One day I’ll have it sorted out.

Fannie was aged twenty one when she married her step-second cousin Sidney Daley, who was (probably) no blood relation to her whatsoever. At this time, Evelyn was aged four so Fannie was about sixteen when Evelyn was born.

Finding Evelyn’s father is the new challenge. We know Evelyn’s birth date from her own memory. She passed away in 1974 and wrote her date of birth on many documents, but no birth record has been found. This research will be quite interesting.

There’s nothing like a DNA test for shaking the tree!

![John Glover (artist) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://historybylarzus.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/natives-on-ouse-river.jpg?w=660&resize=660%2C447)

![By http://www.geographicus.com/mm5/cartographers/dower.txt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://historybylarzus.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/hamilton-district.jpg?w=660&resize=660%2C635)

![By JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://historybylarzus.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/stmatthewschurchnn.jpg?w=300&resize=300%2C200)

![Portion of 1837 Dower Map of Van Diemens Land. Public Domain map By http://www.geographicus.com/mm5/cartographers/dower.txt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://historybylarzus.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/van-diemens-land-1837.jpg?w=660&resize=660%2C436)